Finding fresh water

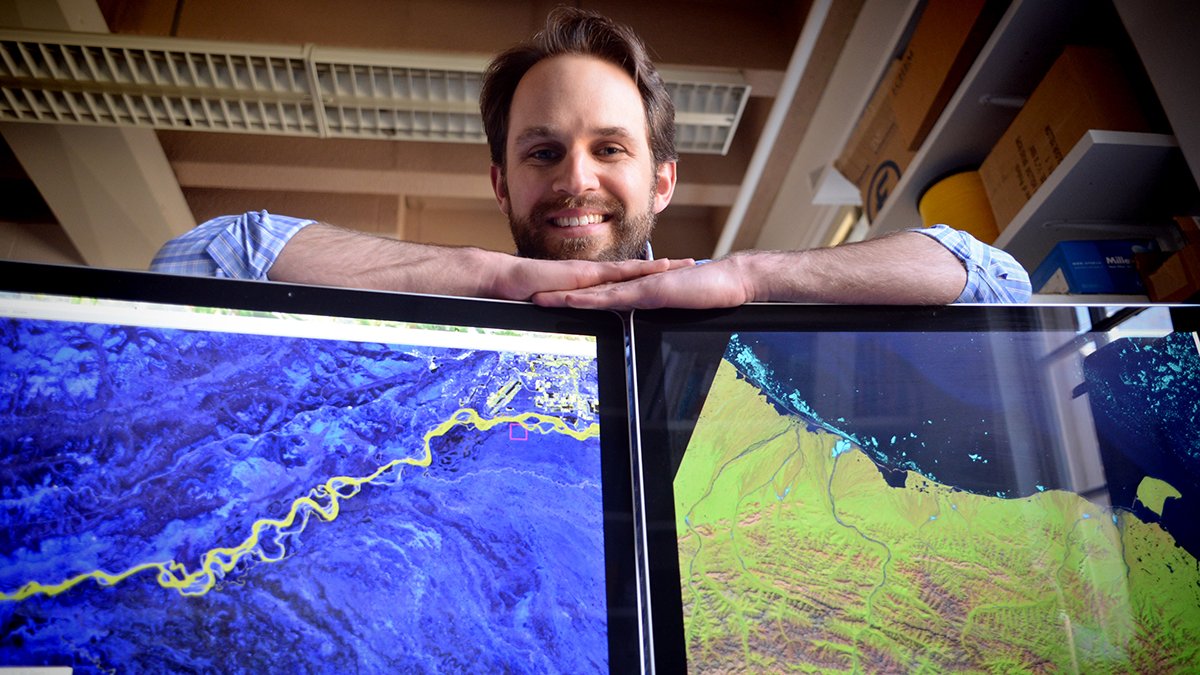

Carolina global hydrologist Tamlin Pavelsky studies how to get more accurate estimates of the world's freshwater supply.

How much fresh water is there around the world? The question seems like it would have an easy answer but UNC’s Tamlin Pavelsky will tell you that’s not the case.

It turns out, if we need to know, for example, the total amount of water flowing through our rivers, the best estimate available could be off by about 40 percent. “We fundamentally don’t really know,” Pavelsky says.

The answer, though, may come from miles above Earth’s surface.

As a global hydrologist in the geological sciences department at UNC, Pavelsky is studying how to get more accurate estimates of Earth’s freshwater supply. Because of his leadership in this field, Pavelsky has been awarded a prestigious Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers. He will be at the White House this month to accept the award.

More accurate estimates of our fresh water supply will help scientists and others in many ways. For instance, communities will be able to better prepare for floods. Scientists will gain a better understanding of the water cycle. The answers will also help scientists understand how global climate change is affecting Earth’s water cycle.

Using conventional, ground-based methods to measure the water in rivers, lakes, wetlands and other bodies of water is one way to estimate the freshwater supply, but that doesn’t provide a full account for several reasons, Pavelsky says. First, in some parts of the world, such as China and India, the government doesn’t release the data. In other parts, nobody is taking measurements. In parts of Africa, for example, the needed infrastructure simply doesn’t exist.

To get a more accurate picture of Earth’s freshwater supplies, Pavelsky turns to satellite imagery. Measurements from satellites can show what is happening on a day-to-day basis as well as provide consistent measurements that date back more than 30 years to reveal how bodies of fresh water have changed.

In December 2013, Pavelsky took on a large job with NASA, when he was appointed the lead U.S. scientist for hydrology for an upcoming NASA/France joint satellite mission called the Surface Water Ocean Topography mission, or SWOT. Using radar technology, SWOT will provide the first global survey of Earth’s water and measure how bodies of water change over time. The satellite will survey at least 90 percent of the Earth and study lakes, rivers, reservoirs and oceans about twice every 21 days. Pavelsky says the technology will provide scientists with the elevation of each freshwater body within about 10 centimeters of its actual height.

“What SWOT is going to do is it’s going to really help us nail down what’s going on with the water cycle now, and so we are going to have sort of this baseline that we can use to figure out how are things actually changing as time goes on,” Pavelsky says.

The mission launches in 2020, more than five years away, but Pavelsky says the timeline feels astonishingly short. He and others are studying technical aspects of how they will use the data. They also are working with engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at California Institute of Technology to ensure the correct design of the satellite.

“No one has ever flown a satellite like this before. It’s completely novel technology,” Pavelsky says.

Pavelsky’s role with SWOT began in 2004 when he was a graduate student at the University of California-Los Angeles and participated in initial meetings about the mission and conducted some research related to it. His involvement increased after he became an assistant professor at UNC in 2009. In summer 2012, Pavelsky hosted a workshop at Carolina with scientists from around the world on how data collected from the mission will be used to measure flow through rivers. Over time, he took on more of a leadership role, culminating with his appointment this past December as the U.S. leader for the hydrology sciences part of the mission. Other scientists from the U.S. and France lead the mission’s oceanography study.

“This project overall is bigger than any single professor or researcher proposing it,” Pavelsky says.

Pavelsky says he grew up hiking and canoeing along remote rivers in Alaska, where he was born and primarily grew up. The experience “gave me a deep love and appreciation for the movement of water across the landscape,” he says.

In graduate school, he focused on understanding the Arctic river systems.

“I’ve always loved maps and other spatial representations of the landscape, so it was natural for me to study the earth from above using satellite images. Combining these two, I ended up focusing on using satellite images to understand Arctic rivers.”

Now, he’s using that knowledge to study all of the Earth’s rivers.