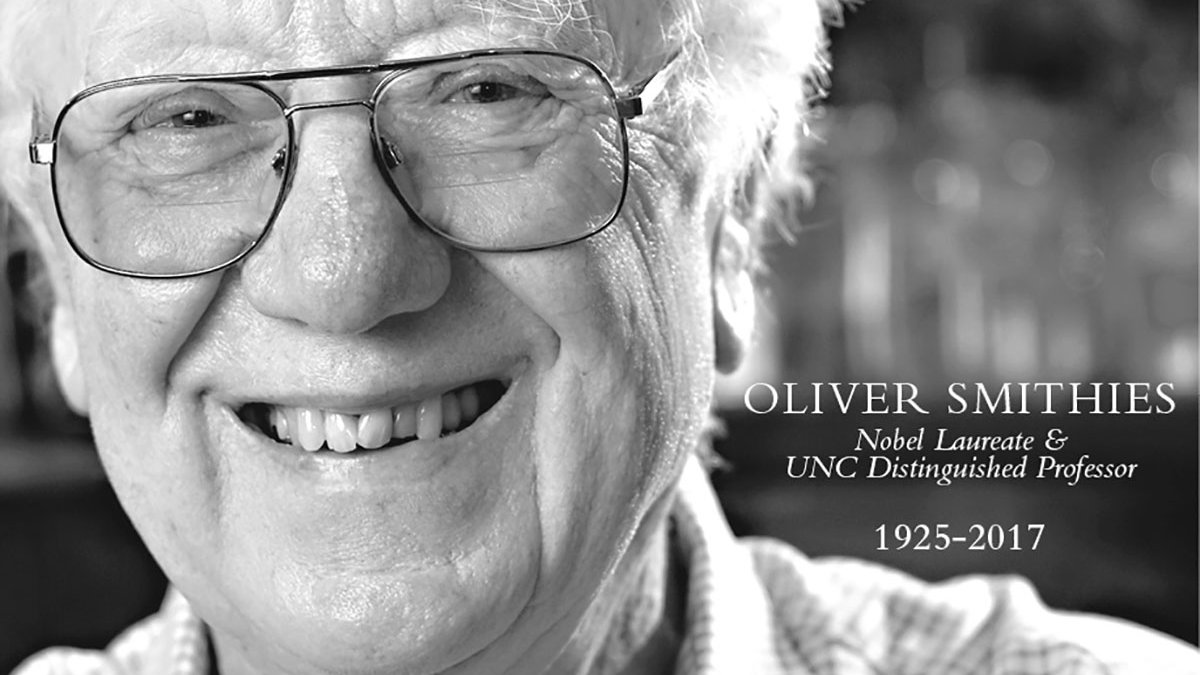

Oliver Smithies, Carolina’s first Nobel laureate, passes away at 91

Smithies is lauded as a brilliant man with an infectious enthusiasm for life and science.

Dr. Oliver Smithies, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s first full-time faculty member to win a Nobel Prize and a world-renowned giant in the field of gene targeting, passed away Tuesday, Jan. 10, at UNC Hospitals after a short illness. He was 91.

Smithies, the School of Medicine’s Weatherspoon Eminent Distinguished Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, received the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 2007 for his development of a technique called homologous recombination that introduced targeted genetic modifications to cells. He shared the prize with Mario Capecchi, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator at the University of Utah, and Sir Martin Evans of the United Kingdom.

Smithies is survived by his wife, Dr. Nobuyo Maeda, Robert H. Wagner Distinguished Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine in the School of Medicine. They joined the Carolina faculty in 1988.

“Oliver Smithies was such a loving, wonderful force for all things good in this world,” said Chancellor Carol L. Folt. “Spending time with Oliver and Nobuyo has been one of the highlights of my tenure at Carolina. Every time I saw the two of them together, I was uplifted and inspired by their relationship, joyful attitude to life and generosity of spirit.”

Smithies’ work made possible the creation and use of “knockout mice,” which have contributed significantly to scientists’ understanding of how individual genes work. Knockout mice also have been used to study and model varieties of cancer, obesity, heart diseases and other diseases. Smithies’ lab at UNC-Chapel Hill created the first animal model of cystic fibrosis in 1992.

Smithies was credited with many notable scientific achievements. Much earlier in his career, while working as a research scientist at the Connaught Medical Research Laboratory in Toronto, Canada, Smithies invented a process called starch gel electrophoresis, the immediate forerunner of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, a method still in use today.

Carolina colleagues praised Smithies’ generous spirit, as well as his remarkable discoveries that have – and will continue to have – beneficial effects on many scientific and medical disciplines.

“Our dear friend and colleague, Dr. Smithies, was a giant and a wonderful human being. The UNC School of Medicine is much the better for his time with us,” said Dr. William L. Roper, dean and Bondurant Professor, School of Medicine, and chief executive officer of UNC Health Care.

“Oliver was a truly remarkable person with a joy for life and science. His brilliance was paired with infectious enthusiasm that inspired everyone around him,” said Dr. J. Charles Jennette, Kenneth M. Brinkhous Distinguished Professor and chair of the department of pathology and laboratory medicine.

In 2015, Smithies helped lead the Carolina community’s celebration of Dr. Aziz Sancar’s Nobel Prize in chemistry. “It was an honor to have Dr. Smithies as my colleague and to have collaborated with him at UNC,” said Sancar, Sarah Graham Kenan Distinguished Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics. “He was a true scholar and a gentleman, an inspiration to all of us here and to scientists around the world. I feel especially lucky to have gotten to spend so much time with him over the past year due to our connection as UNC Nobel Prize recipients. I will miss him greatly.”

Dr. Norman E. Sharpless, director of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, said Smithies played a critical role in the University’s evolution into a world-leading scientific juggernaut. “While many people contributed to that progress, Oliver was one of the most important, by providing the example of research excellence,” Sharpless said. “His discoveries in gel electrophoresis and gene targeting inspired a generation of biologists, including me.”

Smithies and his fraternal twin brother, Roger, were born on June 23, 1925, in Halifax, England. Smithies’ childhood was happy but uneventful, except for a bout with rheumatic fever at age 7 that left him with a heart murmur. At the time, however, the condition was regarded as serious enough that he was not permitted to play sports until he was a teenager.

Smithies filled his hours by reading, a pastime encouraged by his mother, an English teacher at the local community college, and tinkering, building telescopes and radio sets, and helping his father, an insurance salesman, maintain the family car.

In 1943, he received a scholarship to Oxford University, where he briefly studied medicine before changing the concentration of his studies to physiology. He received his bachelor’s degree in physiology in 1946, and went on to earn his master’s degree and doctorate in biochemistry from Oxford in 1951.

Smithies performed postdoctoral work at the University of Wisconsin before joining the Connaught Medical Research Laboratory, where he worked from 1952 until 1960. It was here that Smithies developed his starch gel electrophoresis technique. The high-resolution gels that Smithies created with his new method allowed researchers to study blood proteins much more effectively. Previously, scientists thought blood plasma contained five different proteins. Smithies found 25 proteins in all and also determined that all people have very different mixtures of proteins in their blood.

Smithies returned to the University of Wisconsin in 1960, where he was one of the first scientists to physically separate a gene from the rest of the DNA of the human genome. In 1982, Smithies recorded in his notebook an experimental plan to modify specific genes. The method for targeted modifications in genes – gene engineering – that resulted from these experiments has become an indispensable part of the toolbox for experimental genetics, allowing researchers to understand the function of specific genes in physiology and pathology, and playing a key role in the development of new treatments for a variety of diseases.

When Smithies came to Chapel Hill, his research continued to use gene targeting to create animal models to study human diseases to better understand their cause and progression, and to help develop new modes of treatment. His most recent research focused on hypertension and kidney disease.

Until his passing, Smithies was still at the lab bench seven days a week, pursuing his research with the same enthusiasm that has animated his scientific career for more than 70 years. He was especially excited about a new project he planned on starting after the new year. In addition to his work, Smithies was an avid pilot and especially fond of gliding.

Last fall, the University launched the Oliver Smithies Research Archive website to make available to the world the 150-plus notebooks where Smithies meticulously recorded his notes daily. Smithies began the habit as a graduate student at Oxford, and his notebooks contain information about his research and other details of his life.

Plans to celebrate Smithies’ life are pending.

Selected Awards:

- Member, U.S. National Academy of Sciences, 1971

- Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1978

- Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1986

- Gardiner Foundation International Award, 1990 and 1993

- Alfred P. Sloan Award, General Motors Foundations, 1994

- Ciba Award for Hypertension Research, American Heart Association, 1996

- The Bristol Myers Squibb Award, 1997

- American Association of Medical Colleges’ Award for Distinguished Research (with Mario Capecchi), 1998

- Foreign Member, Royal Society, 1998

- International Okamoto Award, Japan Vascular Disease Research Foundation, 2000

- Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research (with Martin Evans and Mario Capecchi), 2001

- Max Gardner Award, the University of North Carolina system’s highest faculty honor, 2002

- Massry Prize, Meira and Shaul G. Massry Foundation (with Mario Capecchi), 2002

- Member, U.S. Institute of Medicine, 2003

- Wolf Prize in Medicine (with Mario Capecchi and Ralph L. Brinster), 2003

- Thomas Hunt Morgan Medal, Genetics Society of America, 2007

- Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 2007

- Gold Medal, American Institute of Chemists, 2009

- Honorary Degree, Doctor of Science, Oxford University, 2011

- Charter Fellow, National Academy of Inventors, 2013

- Faculty Service Award, UNC General Alumni Association, 2014

Smithies in His Own Words:

Interview with the 2007 Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine conducted by Nobelprize.org with Smithies and his co-recipients.

2001 Commentary article from Nature that talks about scientific tool making and details several of the experiences over the course of his career.

Autobiographical remarks from 2007

2015 interview with PLOS Genetics

What people are saying about Smithies:

UNC-Chapel Hill Chancellor Emeritus James Moeser:“I am deeply saddened by the news of Oliver Smithies’ death. When I think of Oliver, I think of two words – love and joy. Oliver loved his work and took real joy from it. He was never happier than when he was in his lab. He loved his wife Nobuyo, who was his full partner in research, and he loved his colleagues and his students, who all loved him in return. Oliver also loved to fly his plane, which he kept based at Horace Williams Airport, and he told me once, that whenever he had a problem to solve, he would go for a flight. Every time I saw a small single engine plane overhead, I imagined it was Oliver. We had a big ceremony in Memorial Hall to honor Oliver for winning the Nobel Prize, and I was able to announce that from that time forward, anyone winning the Nobel Prize would have a reserved parking place for life. Oliver loved that parking place. He was a joy. I shall really miss him.”