Remembering the true moments

Understand this: this man could do anything. This man could coach and this man could help integrate a town or a league and this man changed the lives of hundreds of teenagers who played for him plus thousands of the rest of us who lived vicariously through their exploits.

I have been sitting here staring at this screen for 30 minutes. And what I have finally decided I want you to know the most about Dean Smith is this: it’s true.

In the next few hours and days, as the tributes to the legendary man pour in, you are going to hear all of the incredible stories again. Some you may hear for the first time. Some you may hear for the hundredth time. These stories are true, and you should remember all of them, because now it’s our job to pass them down. Don’t embellish them. They don’t need it. They are good enough with just the facts.

You will hear basketball stories. You will hear former players talk about how Smith would tell them exactly what was going to happen in a game. He would tell them what the opponent would do, how the Tar Heels would react, and how the opponent would react to that reaction. Then it would happen, all of it, just as he described.

These stories are true. We know this because we sat in Carmichael in 1974 when his team came back from eight points in 17 seconds against Duke with no three-point line. I just told that story to my children on Saturday night when we drove home from the airport after returning from the win at Boston College. My nine-year-old son was talking about a crazy NBA comeback he’d read about.

“Do you know,” I said, “that Carolina came back from eight points down in 17 seconds with no three-point line?”

“Whoa,” said my daughter. “Is that true?”

It is true.

Those of us of a different generation than the Carmichael crowd were in the Smith Center when Smith’s simple act of calling a timeout so shook a top-20 opponent that they meekly crumbled. I will forever believe that’s what happened when Smith took a timeout after Henrik Rodl made a three-pointer against Florida State with less than ten minutes left on the clock in 1993. Rodl’s three-pointer had cut the FSU lead to 17 points. 17 points!

It didn’t matter. All that mattered was that the Florida State players and coaches knew Smith thought a comeback was possible, or else he wouldn’t burn one of his precious timeouts. And if Smith thought a comeback was possible, then it was possible, and he’s done this before, you know, and uh oh, there went another turnover, and it’s getting kind of loud in here, and pretty soon Carolina had an 82-77 win.

That was true. That happened. Dean Smith called a timeout, and Florida State wilted.

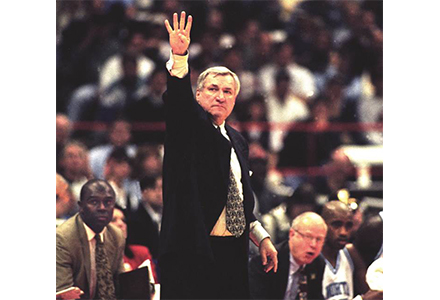

And yet despite all those wins, we know exactly how uncomfortable Smith was with celebrating any of them. I can report, with authority, that with much cajoling from his players, he once did the “raise the roof” gesture after his Tar Heels won the 1997 ACC Tournament championship, and then again after earning a spot in the Final Four. It was the mid-1990’s. Everyone made mistakes.

Otherwise, however, the man who never looked flustered on the sideline looked completely awkward in victory. He would almost apologetically shake the other coach’s hand. If it happened to be an ACC or NCAA championship, he would try to disappear while the nets were being cut, so unwilling was he to climb the ladder and be the focal point of the fans and players.

Most of the time, those of us in the stands would chant, “Dean! Dean! Dean!” when he was finally persuaded to cut the final snippet. It seems a little disrespectful now. But it was the 1980s and 1990s. All of us made mistakes.

It didn’t really matter, because he would act like he didn’t hear us. With scissors in hand, before cutting the first strand, he would point to every manager, player and assistant coach he could find.

That was true. That happened after every championship, and there were a lot of them.

There are also those who will tell you those championships are completely insignificant. Funny thing about the people who most often say that: they are invariably the ones who knew him best, the ones who most understood his true character.

“I can’t put his impact on me into words,” Phil Ford said of Smith. “I don’t know where I’d be without him in my life. He’s been such an influence on me, and a friend and a brother and a father figure…Before I chose North Carolina, I felt that Coach Smith would be there for me my entire life. I was right.”

Imagine that. A 17-year-old boy felt Dean Smith would be there for him for his entire life, and 40 years later, he still believes it. Wouldn’t you like to have one person say that about you in your life? Dean Smith has—this is not an exaggeration—hundreds.

“All of that is credited to him,” Michael Jordan once said of his career. “It never would have happened without Coach Smith.”

These quotes mean a lot to us because they are from Phil Ford and Michael Jordan. But what Smith knew, and what he made every one of his players feel, is that the number of points they scored for him made absolutely no difference. My father and I had a joke in the mid-1990s. Carolina had a player named Pat Sullivan who was not at all flashy. At various times, he played on teams with George Lynch and Eric Montross and Rasheed Wallace and Jerry Stackhouse, much better-known players who were prone to occasionally doing the spectacular.

It never, ever failed: Stackhouse could have had the most ferocious dunk of the season and Wallace could have thrown down an absurd alley-oop and Montross could have had a double-double and Lynch could have had the game-winning steal. Then, in the car on the way home, we would turn on the Tar Heel Sports Network to hear Smith’s postgame comments and seemingly every time, they would start with, “Well, Pat had a good game,” because he had set a screen to free a teammate for an open shot that the teammate missed.

That happened. Pat had good games. Dean Smith talked about it. At the time, we laughed, and yet 20 years later, we still remember it.

This seems like the right time to point out that without ever really knowing he was doing it, Dean Smith gave all of us some of the best moments of our lives with the most important people in our lives. It doesn’t matter whether you attended every game in the Smith era or whether you watched every game on television. Because of the way Smith did it, and for how long he did it, we could relate through generations.

We cried in the living room (I did that, after Louisville beat Carolina in 1986 in the NCAA Tournament) and we danced around that same living room (my dad and I did that, after Rick Fox hit the shot against Oklahoma in 1990) and we high-fived in the stands.

That’s what we did in 1993 in the Louisiana Superdome. My dad is an accountant and therefore spends most of March and April at the office. But when Carolina made the Final Four, he would find a way to get to the game. In 1993, he waited until the Tar Heels defeated Kansas in the national semifinals. He stayed at work two more days, then caught a flight with two connections from Raleigh to New Orleans. He slid into his seat minutes before the national championship game tipped off against Michigan, and so I can say that I watched Carolina win the national title with my dad.

We went to Bourbon Street after the game, because that’s what everyone told us you were supposed to do, and so there we were—perhaps the two least Bourbon Street-ish people in all of New Orleans, including one CPA with a pile of unfinished tax returns on his desk back in Raleigh—high fiving the Tar Heel players and taunting Dick Vitale (who had picked Michigan to win the game), and we did all of that because of Dean Smith.

Without Dean Smith and Carolina basketball, I assume and hope we would have found something else to talk about and live together. But because of Dean Smith and Carolina basketball, I never have to know for sure if that’s true.

And so that is why this news will be devastating to so many of us. About a year ago, I was at the Smith Center on a typical weekday afternoon. A customized van was parked in the first parking space outside the basketball office, and I knew. As I walked into the basketball office, Dean Smith came out, being pushed in a wheelchair, a Carolina hat on his head.

It was awful, and it makes my eyes moisten even now to think about it. It was not at all the way I wanted to think about him. And I would like to admit something to you now: from then on, when I saw that van, I would sometimes take a different path into the building, because I wanted my Dean Smith to be the one I remembered. I wanted my Dean Smith to be the one who I mentioned my daughter’s name to on exactly one occasion, and six months later when passing me in the parking lot, he recalled it perfectly and asked how she was doing.

That’s my Dean Smith and I wanted that to be everyone’s Dean Smith. I don’t want today’s students to think of him as old or sick. Understand this: this man could do anything. This man could coach and this man could help integrate a town or a league and this man changed the lives of hundreds of teenagers who played for him plus thousands of the rest of us who lived vicariously through their exploits.

It still boggles my mind that so many Carolina fans in 2015 don’t even remember the era when Smith was on the sideline. He’s as much a name on a building as a coach to current UNC students. It’s been hard enough living in a basketball world without Dean Smith in it. Now we have to consider living in an overall world without Dean Smith in it.

I don’t want to be part of that world. And luckily, I don’t have to. On Monday, I will pack my son’s lunch, and I will write a Dean Smith quote on the napkin. I don’t know yet which one it will be, but I know that when I see him on Monday afternoon, I will ask him about it, and we will talk, and Dean Smith will be the one who enabled that to happen.

That’s true. That will happen. And it will keep happening, and we are the ones who get to do it. I guess that pretty soon I will feel lucky for having these experiences and getting the opportunity to cheer for him and learn from him and admire him.

But right now I really think I want to sit down and have a good cry.