UNC ‘perfect place’ to study sticky subject

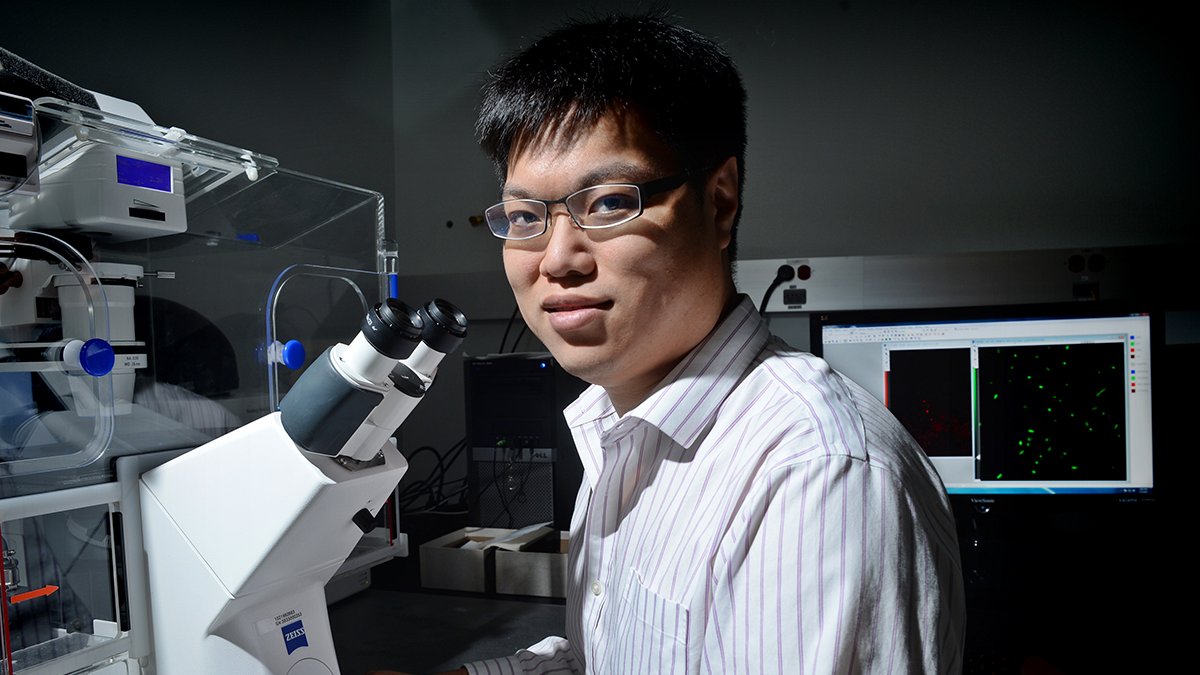

Sam Lai, assistant professor in the Eshelman School of Pharmacy, researches how antibodies in mucosal linings can bolster the body’s defense against diseases.

Mucus might not be the most attractive thing to study, but it’s what attracted Sam Lai to Carolina.

While finishing his post-graduate work at Johns Hopkins University, Lai had his eye on the research coming out of UNC. There was the Cystic Fibrosis and Pulmonary Research and Treatment Center, the Center for Infectious Diseases, a stellar Department of Microbiology and Immunology, and a group of applied mathematicians, chemists and physicists putting their heads together on the role of mucus in the body.

He knew there were like minds at Carolina.

“The fact is, what I’m working on has rarely been studied because people don’t like working with mucus,” Lai said. “It’s not in the mindset of a lot of researchers.”

Though it’s an unpleasant topic, it’s one that Lai thinks will save lives. The assistant professor in the Eshelman School of Pharmacy has been well recognized – by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the National Science Foundation – for his inventive research on how the antibodies in our mucosal lining may be used to bolster the body’s defense against diseases.

He’s now been awarded a prestigious Packard Fellowship for Science and Engineering, a five-year $875,000 award that recognizes the nation’s most innovative young scientists, which will give him the freedom to lead his lab toward a solution.

Engineering better lives

Lai was studying engineering at Cornell University when an engaging course on drug delivery showed him how an engineering background could be valuable to modern medicine.

“It opened my eyes. There is so much improvement that can be made in medicine simply by getting the drug to where it’s needed,” he said.

Born in Hong Kong, Lai came to America to attend Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass. He watched his friends back home move into banking and finance. He even tried an internship in investment banking, but he knew that wasn’t for him.

Other things weighed heavily on his mind: health care and education.

“I see them as the two pillars of modern society, and wanted to figure out how to work at the interface of those two things, so research on ways to improve medicine made a lot of sense to me. Without health, people can’t be productive in their efforts. Without education, they can’t contribute in the ways they want,” Lai said.

He spent his graduate and post-doctoral years at Johns Hopkins, where he set out to find a medical problem that few people were working on – and fix it. He began to explore ways that would deliver drugs right to the mucosal surfaces that line our body’s systems, like airways or the gastrointestinal tract.

Because drugs delivered intravenously often reach mucosal sites with very low efficiencies, finding ways to directly deliver medicine to those linings made sense to Lai. “But, there’s no sustained delivery of medicine to a mucosal surface – we had to overcome the mucus barrier, which continuously cleanses most foreign particulates from the body.”

His team was able to make a synthetic particle that could penetrate the mucus barrier for localized therapy, and they began to transition the technology to a start-up company. He’d found his passion – using early-stage technology research to solve medical problems – but it led him to think about a different problem.

“Because I’d spent so much time trying to get things to go through mucus, I just stopped and thought about the other side. Was there anything we could do to better keep pathogens from passing through those linings in the first place?” he said.

The mucosal lining is also the way we absorb nutrients, so the solution had to allow the good things to get in while keeping the bad things out.

Lai is studying how pathogens behave in mucus and how they interact with the antibodies our immune system secretes directly into the mucus. These antibodies can actually work together with mucus to prevent infection from occurring in the first place. The work will contribute towards engineering – or inducing – antibodies that can better reinforce our body’s first line of defense.

“Our perspective is that this should help with virtually all infections that transmit in mucosal surfaces – influenza, the common cold, norovirus and various sexually transmitted diseases,” he said.