Your brain on electricity

Something much subtler than ECT could be the new way to treat mental illness.

You’re hearing things.

All the time. Your brain continuously takes in messages from your auditory system—a cascade of data that, if you paid attention to all of it, would drown out your thoughts in a cacophony of sound.

If it weren’t for your prefrontal cortex, you might think that the sound of running water was a human whisper, or that the wind contained a secret message. But the decision-making part of your brain sorts out this onslaught of auditory information, so that you know when you’re hearing a baby’s cry, or a dog’s bark, or nothing at all.

In short, if your prefrontal cortex didn’t work so well, you’d have auditory hallucinations—much like the effects of schizophrenia. In fact, even a healthy person can occasionally hallucinate sounds, says UNC-Chapel Hill neuroscientist Flavio Frohlich. It’s just a glitch in the electrical firing of neurons between your auditory and prefrontal cortices.

In schizophrenia, that glitch becomes a pattern. And Frohlich thinks he can change the pattern—painlessly, without drugs or side effects—by manipulating the brain’s electric field. Five years ago, this would have sounded like junk science. But it’s real, and there’s good reason to think that someday soon, psychiatrists will prescribe low-grade electric stimulation alongside drugs and talk therapy.

First, let’s clarify—this isn’t electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT.

Since before psychiatric drugs were invented, doctors have been using ECT to treat depression. Neurons, the cells that make up the brain, communicate with each other in faint electric pulses. A sudden, intense pulse of electricity to the brain causes billions of neurons to activate all at once. When they quiet down, they seem to “reset” to a less depressed pattern. But the treatment causes serious memory problems and requires the patient to go under anesthesia.

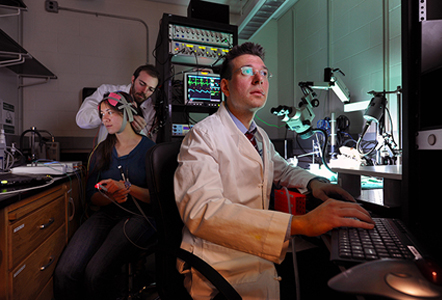

Enter the electrical engineer. Frohlich, who spent his undergraduate years learning how to manipulate complex electrical systems, is far too precise to ever turn a powerful, unfocused electric current on the brain. Instead, he works with small, carefully targeted electrical pulses, only a tiny fraction of the strength of the current used in ECT.

Administered through wet sponges sitting on the patient’s head, transcranial direct-current stimulation (TDCS) is usually painless. Many people can’t even feel it. Some experience a little itching or—especially if they’re bald—some redness on the scalp that fades quickly. The current is so subtle that it doesn’t completely take over what neurons are doing. It just changes when, exactly, they fire.

Up until a few years ago, scientists thought that the brain’s electric field was a byproduct, an echo, of the tiny electric pulses passing between neurons in your brain. But then a few researchers, Frohlich among them, demonstrated that the field helps regulate neural activity and synchronize neurons. That is, the electric field around the brain helps neurons talk to each other.

This got Frohlich excited, because it meant that if he could change the field, he might be able to change what goes on in the brain. Other researchers leapt into action too. TDCS requires only some very basic electrical equipment, so labs around the world quickly began studies to stimulate people’s brains in a new way.

What did they find TDCS could do?

To continue reading this story, see Endeavors.