Why a fly?

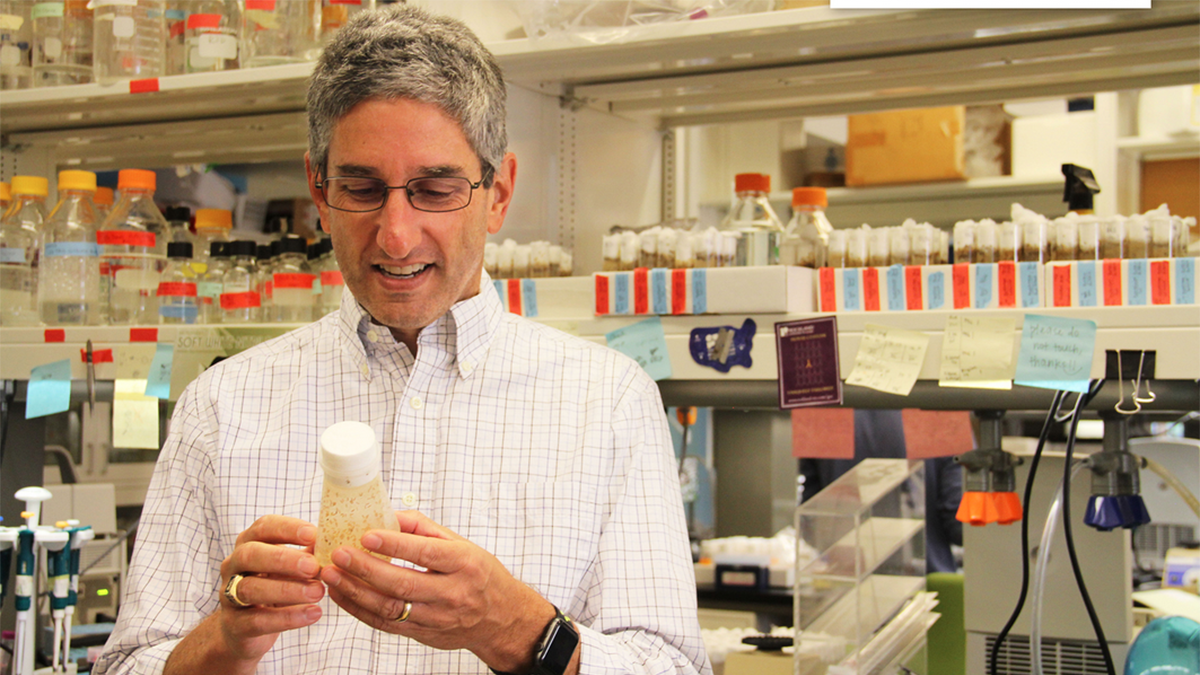

The genome of a fruit fly is strikingly similar to that of a human — so much so that scientists have been studying these tiny insects for over 100 years, in search of treatments for diseases like spinal muscular atrophy and neurological disorders. Carolina geneticist Bob Duronio is one of those scientists.

“Beautiful.”

Robin Armstrong adjusts the focus on her dissecting microscope. Iridescent ovals float in the ether, clumped together, stark against a black backdrop. They look like the little, individual fibers that comprise the flesh of a grapefruit — long and plump and juicy. Though this grape-shaped bunch is far from produce, it’s fitting that they belong to a fruit fly. Armstrong is examining its ovaries.

“These giant cells down here are nurse cells,” she says, motioning to the shimmery blob she just removed from her specimen with tiny forceps. She points to a gap. “And that’s where the developing egg cell is. This is my favorite stage of fruit fly reproduction — there is some pretty cool biology that happens here.” Armstrong, who is pursuing a doctorate in the UNC Curriculum for Genetics and Molecular Biology, studies fruit flies in the Duronio lab to uncover how DNA replicates inside cells.

The intricate, specialized processes of DNA — things like replication and repair and segregation — work, essentially, the same way between fruit flies and humans at the molecular level. In fact, fruit flies share approximately 75 percent of the genes that cause disease in humans, making them a perfect tool for scientists to study human gene function. And the more we know about how genes function, the easier it becomes to develop medicines that can treat a variety of diseases.

To understand how fruit flies help us find treatments for human diseases, it’s important to first understand cell division — a fundamental mechanism for all life. Remember learning about mitosis in sixth-grade biology? The process begins with a parent cell, which splits into two, identical daughter cells.

But this doesn’t always go according to plan. When a cell divides incorrectly or at the wrong time, diseases like cancer can occur.

“For normal animal development to occur, meaning the healthy maintenance of functioning organs, there needs to be just the right amount of cell division — but not too much — at the right time and in the right places,” Carolina geneticist Bob Duronio says.

Human disease can happen when control over the time, place, and/or amount of cell division is lost. A lack of division can lead to disease — but an exponential increase can as well. Think of it like “Goldilocks and the Three Bears,” says Duronio. “It has to be just right.”

Fruit fly “why”

Biologists refer to species that are studied to better understand human biology as “model organisms.” Fruit flies fall into this category, as hundreds of labs across the country dedicate their research to these tiny beings. In the Genome Science Building, alone, six labs focus on fruit fly research. “Even though they’ve been studied for over a hundred years, there are still people in the biomedical community who say, ‘Why do you work with fruit flies?’” Duronio says. “Part of my job is to explain that.”

Beyond genetic similarity, fruit flies are relatively low-maintenance organisms — they’re small but big enough to see under a microscope, reproduce quickly and abundantly (a female fruit fly lays between 750 and 1,500 eggs in her lifetime) and only need their food changed every 10 to 14 days. Plus, they’re easy to “push.”

“If you ever hear the term ‘fly pushing,’ that literally means we’re pushing them around under a microscope,” Armstrong says. The term stems from the physical action occurring under the microscope, as researchers push the flies around to identify specific traits like eye color and bristle shape, which they use for genetic crosses. “Now it generally means the act of fly genetics — because we always have to sort flies for our crosses,” she says.