School of Government publishes first graphic book

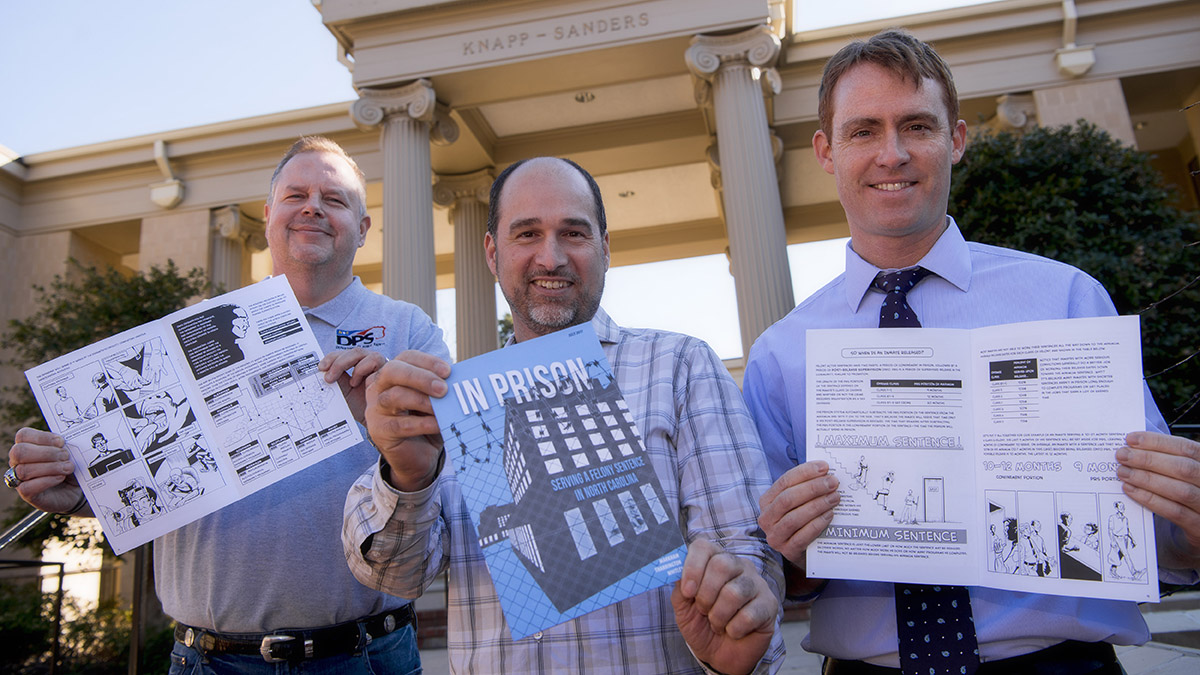

N.C. Department of Public Safety and University employees combined their talents to create the School of Government’s first graphic book, which helps to explain the state prison system in words and pictures.

As a faculty member in the School of Government who writes for the N.C. Criminal Law blog, associate professor Jamie Markham often hears from people who really don’t know how the prison system works.

“I get a lot of mail and phone calls from victims, inmates and their families,” he said. “It is clear to me from their questions that they don’t always have a clear sense of how a defendant’s sentence will play out in practice.”

Wouldn’t it be great, he thought, if there was a book he could give these non-experts that could quickly explain the process in a way that was easy to understand, using drawings and simple language?

Now there is.

In October, the UNC School of Government published its first graphic book, In Prison: Serving a Felony Sentence in North Carolina. The text was written by Markham with help from N.C. Department of Public Safety employee Shane Tharrington and illustrations by Jason Whitley, a staff member at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy.

The publication describes how a felony sentence is served in North Carolina, following an inmate from the moment the judge pronounces the sentence to the day the inmate completes post-release supervision.

Intended primarily as a reference for crime victims, defendants or their family and friends, the book helps translate the words and numbers on a criminal judgment into a practical explanation of how long a person is likely to be incarcerated. The publication explains where and how time will be served and shows the types of work and programs in which an inmate might participate to get a sentence reduced.

A different audience

Whitley’s illustrations help flesh out Markham’s narrative, translating the complicated interworking of a criminal judgment into everyday language.

“It serves a different audience. Some see a sea of words and they’re just not interested, and they’re trying to find out what they need,” said Whitley, creative lead for educational design and innovation at the pharmacy school. The graphic book version is “a lot quicker and more concise to read.”

Tharrington, manager of inmate classification and mainframe technical support for prisons, provided an insider’s view ofprisons for the book. He worked at Central Prison in Raleigh for 19 years.

“I’ve been working with Jamie for a number of years, coming over and speaking to and with his classes about how adult corrections’ prisons work in the greater criminal justice scheme,” Tharrington said. “He mentioned the book to me and asked if I would help him with the subject matter. I told him I’d be glad to. It was really an honor to be asked to do that.”

Tharrington even arranged a tour of Central Prison for Markham and Whitley. “I bet it was interesting for them to see how orderly and clean those places are. A lot of people have these images from TV and movies, and it’s really nothing like that,” Tharrington said.

The prison tour was the high point of the experience for Whitley. “There are not a lot of backgrounds in the book, but we did the research. We wanted everything to look right,” he said.

Communication in the system

The project addresses the larger issue of communication within the state’s criminal justice system, Tharrington said.

“It’s been really good to share information back and forth because I’ve always said that’s one of the biggest problems in criminal justice—that Prisons doesn’t communicate with Community Corrections and Community Corrections doesn’t communicate with the courts and the courts don’t communicate with local law enforcement,” he said. “But the more communication we can do between all the disciplines, the better it will be and the smoother [the system] will work.”

The school’s first graphic book has another unique feature—it is printed by Correction Enterprises, which provides vocational training to inmates through the N.C. Department of Public Safety. Correction Enterprises consists of 32 separate revenue-producing operations. Working on book printing or any other job at Correction Enterprises would generally yield nine days of earned time per month, reducing these inmates’ sentences.

“Jamie and I both thought it would be great in that it would give them some ownership in it, and it would also just show people from the outside who would see this product, this book, [that] inmates are learning how to do things and they’re not just sitting idly in the prisons,” Tharrington said. “We’re offering a number of trades and skills for them to learn so that they can hopefully get jobs and do well when they get out.”

In Prison is the first of what will be a trilogy of graphic books to be published by the School of Government, all related to sentencing and corrections issues and intended for a lay audience. One will cover what it means to be on probation, and another will address serving time in the county jail.