Serving the whole child

World-class researchers at Carolina’s School of Education work to make schools safer, healthier places for learning.

Today’s learners experience an ever increasingly complex world. For K-12 students, research has shown that many factors beyond classroom conditions contribute to effective learning.

At the UNC School of Education, world-class researchers discover and put knowledge into practice to ensure a “whole education,” which works to achieve well-being for students, families and communities and to make schools safer, healthier places for kids to grow up.

Every day, faculty members are pursing ground-breaking research and teaching, with the understanding that effective learning happens best when students are healthy and feel cared for.

21st century solutions to bullying

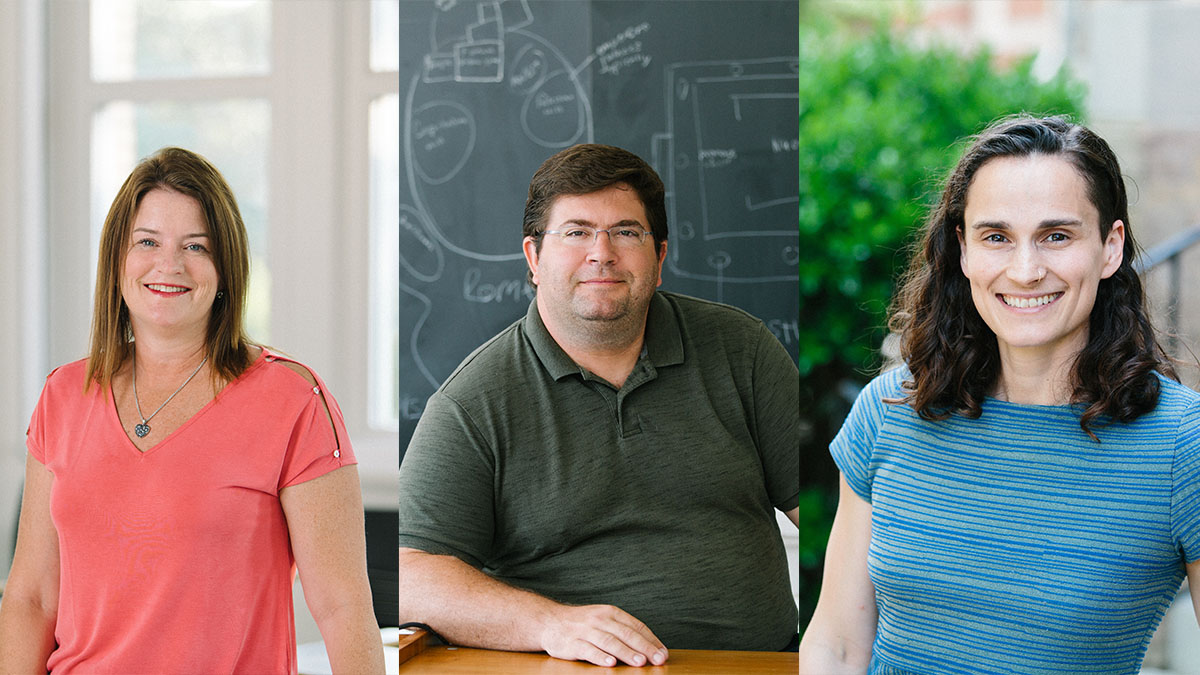

When Congress, Oprah and Anderson Cooper seek to better understand bullying and school violence, they turn to Dorothy Espelage.

One of the leading researchers in evidence-based bullying and school violence interventions, Espelage has spent the past 25 years working to understand the experiences of middle and high school student and creating more positive school climates. She’s shared her research in congressional hearing rooms, in non-profit boardrooms, on national TV broadcasts and in schools across America.

Despite having already earned international acclaim and nearly 25,000 research citations, Espelage has work left to do to break the patterns of bullying and violence in schools.

“One thing we know is that social-emotional learning programs work,” said Espelage, who is the the William C. Friday Distinguished Professor of Education. “It’s this idea that we should teach kids conflict management skills and empathy and emotion regulation, and it reduces bullying largely through improved social connectedness.”

With those findings in mind, Espelage is developing youth-driven programming to address bullying, name-calling, dating violence and other issues in schools.

With input from students and educators, she and her colleagues developed an app called Advocatr, which allows high school students to confidentially report situations where they feel unsafe. She teamed up with Google Virtual Reality to create bully prevention programming that promotes empathy. And she partnered with a colleague to develop a text messaging program for middle school youth to reduce bullying through development of social-emotional learning skills.

“The theme is really leveraging not only technology, but also the youth, who I believe — and have always believed — have something important to say,” she said. “[Bullying] prevention messaging should come from them, for the most part.”

Mental health support

Espelage isn’t the school’s only faculty member focused on understanding students’ needs and finding innovative ways to meet those needs. Marisa Marraccini, an assistant professor in the school psychology program, has also played a key role in keeping students safe by improving mental health interventions.

As a psychologist who has worked in both schools and clinics, Marraccini’s research found that many schools lack re-entry guidelines for adolescents who have been hospitalized for suicidal thoughts or behaviors.

“I knew firsthand, having worked in schools and in hospitals, the transition from the hospital into schools wasn’t being addressed, so it very much justified the need for this work,” she said.

In her analysis of schools across the nation, Marraccini found that many schools don’t have procedures in place to help students transition from a psychiatric hospitalization event back into school. To address that need, she is working with colleagues to develop guidelines for this re-entry period and train school psychologists and counselors in interventions for supporting school safety and student wellness.

“I think there’s a myth that psychiatric hospitalization is going to cure kids, and that they’ll come back and be ready for school,” she said. “Without a plan in place for that, it can leave them left to flounder and struggle.”

Parents can also struggle with the transition, Marraccini said, as some report that leaving the hospital with their child after a psychiatric stay feels a lot like leaving the hospital with a newborn — there is no instruction manual.

But one simple, yet profound, step can ease the transition: parents and teachers can talk openly with kids who are struggling. Marraccini’s research shows that kids who feel more connected to their schools and teachers are less likely to experience suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

“A big part of the message is not backing away, but really moving in to support some of our higher-risk kids,” she said. “It’s such a heavy topic, and it’s hard to talk about. Anecdotally my impression is that kids pick up on that. They know that people are afraid to talk to them about these issues, and they just want people to connect with them and treat them like kids.”

Parent-teacher relationships

Associate professor Roger Mills-Koonce researches how the parent-child relationships can set kids up for academic success even during their earliest years of life.

Research shows that kids respond well to supportive parenting, gaining better cognitive, social and emotional skills. But Mills-Koonce has also found that some kids are more sensitive to their environments and relationships than others.

“That is a good thing in that it provides us an opportunity to step in early on and try to improve their trajectory,” he said. “But then the children who are more challenging can sometimes evoke more negative responses from adults, and that tends to cause a negative cycle and spiral into more persistent and severe behavior problems.”

In other words, through specific mindful parenting and positive attention, parents can have a considerable impact on the way a child behaves once they get to the classroom.

And when a sensitive child reaches school age, Mills-Koonce said, it’s critical for parents and teachers to work together to create a positive environment — particularly for children who have ADHD or who struggle with conduct issues.

While it’s a tall order for teachers to focus attention on students experiencing behavioral issues while juggling a class of 20 or 30, Mills-Koonce said it becomes easier when parents, teachers, coaches and other community members share knowledge and support.

“Teaching doesn’t just happen in the classroom; it happens 24/7,” Mills-Koonce said. “The kids who are the most challenging can also be the most rewarding kids for you to reach, and we really try to push that message for all adults.”

Together, Mills-Koonce, Espelage and Marraccini use their research to reach students at nearly every point on their education journeys, both inside and outside of the classroom, to help them achieve their full potential.