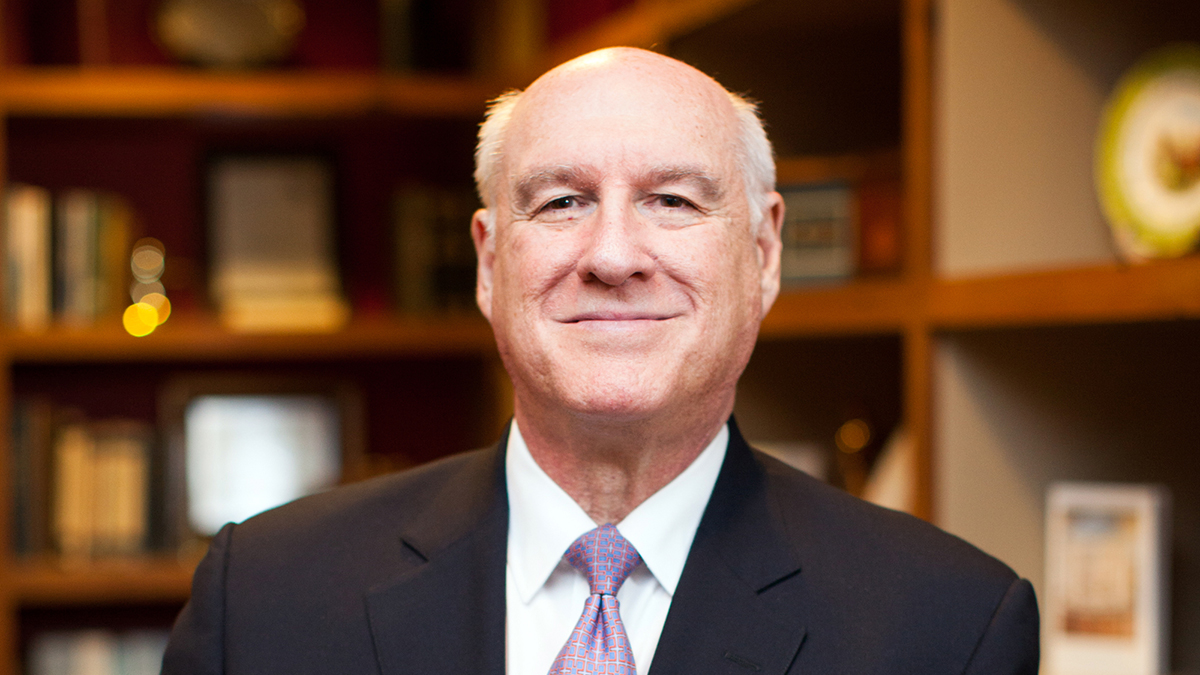

225 years of Tar Heels: Myron Cohen

Dr. Myron Cohen, a professor of medicine, microbiology and epidemiology at Carolina, has made great strides toward eradicating HIV.

Editor’s note: In honor of the University’s 225th anniversary, we will be sharing profiles throughout the academic year of some of the many Tar Heels who have left their heelprint on the campus, their communities, the state, the nation and the world.

Editor’s note: In honor of the University’s 225th anniversary, we will be sharing profiles throughout the academic year of some of the many Tar Heels who have left their heelprint on the campus, their communities, the state, the nation and the world.

In 1981, NASA launched its first space shuttle mission, Ronald Reagan was sworn in as the 40th President of the United States and Prince Charles married Lady Diana Spencer in a ceremony billed the “wedding of the century.”

But something else was quietly taking root at UNC Hospitals that would influence millions of people worldwide for decades. At the dawn of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, Dr. Myron Cohen was treating Carolina’s first patient with AIDS.

That moment marked the beginning of a career dedicated to eradicating HIV. Today, Cohen, a professor of medicine, microbiology and epidemiology at Carolina, has made great strides toward that goal alongside colleagues from UNC-Chapel Hill.

“I think UNC has made some pretty substantial contributions [to HIV treatment and prevention],” he said on Carolina’s podcast in 2016. “We had the privilege of leading the HPTN 052 study that demonstrated that treatment of an infected person effectively eliminates their ability to transmit to the next person. This really changed guidelines worldwide, leading people to earlier and more substantial treatments.”

Cohen’s study represented an unprecedented breakthrough in medical knowledge about the spread of HIV. The results showed that early antiviral therapy could reduce sexual transmission by at least 96 percent, which had immediate and profound impacts on the global approach to the HIV crisis.

But Cohen is not content to stop there.

“Everything’s a Band-Aid except for a vaccine and a cure,” he said. “So what we want is a vaccine that will prevent HIV infection and a cure that will eradicate infection.”

His outlook is positive. Cohen believes it’s possible that the world will see changes in treatment for HIV infected people in the next 10 years that may ultimately lead to a cure. But even if it takes much longer, Cohen and his colleagues at Carolina are committed to pursuing every effort to eradicate the disease.

“We need a vaccine,” he said. “If it takes us 1,000 years, we have to make a vaccine for HIV.”