Carolina scientists discover new method for developing tracers used for medical imaging

The tracers can better track pharmaceuticals in the body as well as image diseases, such as cancer, and other medical conditions.

In an advance for medical imaging, scientists from University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center have discovered a method for creating radioactive tracers to better track pharmaceuticals in the body as well as image diseases, such as cancer, and other medical conditions.

The researchers reported in the journal Science a method for creating tracers used with positron emission tomography, or PET scan. Researchers said their findings could make it possible to attach radioactive tags to compounds that previously have been difficult or even impossible to label.

“Position emission tomography is a powerful and rapidly developing technology that plays key roles in medical imaging as well as in drug discovery and development,” said UNC Lineberger’s Zibo Li, the study’s co-corresponding author, an associate professor in the UNC School of Medicine Department of Radiology, and director of the Cyclotron and Radiochemistry Program at the UNC Biomedical Research Imaging Center. “This discovery opens a new window for generating novel PET agents from existing drugs.”

PET scans track a radioactive tag that is attached to a compound. These tracers are generally injected into the body, and they produce bright images on medical scans as the tracer accumulates in the targeted lesion, organ or tissue. Scientists can attach radiotags to molecules like glucose, which will accumulate in tumors since cancer cells consume a lot of sugar to drive their overactive growth, or to amino acids, which, as the building blocks of proteins, are also highly consumed in tumors. They can also attach them to potential new drugs to track their course in the body.

“What is believed to occur is that tumor molecules uptake these resources faster than healthy cells do,” said David Nicewicz, professor in the UNC-Chapel Hill Department of Chemistry and the co-corresponding author of the study. “What we’ve contributed to the field is a new method to introduce radio-labeled isotopes of atoms into drug molecules in a way that hasn’t been done before.”

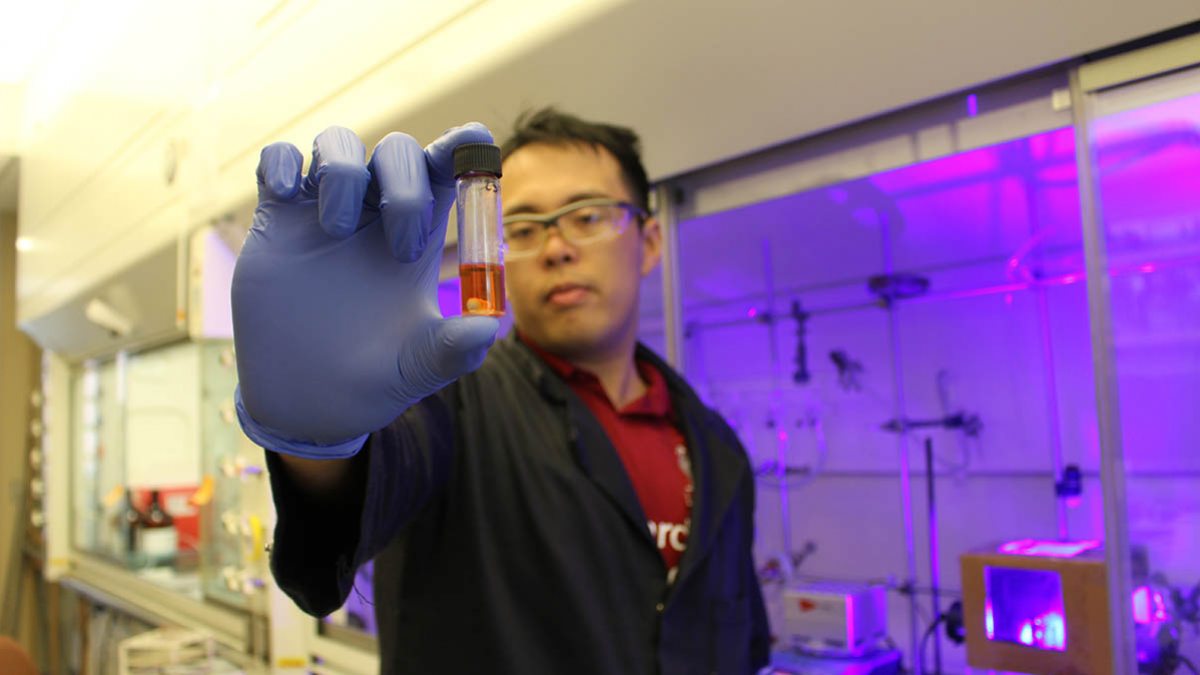

In their study, the researchers described a new way of attaching the radioactive molecule Fluorine-18, the most widely used isotope in PET, by breaking a specific chemical structure of carbon and hydrogen atoms. In the presence of blue light from a laser and after the addition a catalyst material to speed the reaction, the researchers could break existing chemical bonds in the structure and insert Fluorine-18. Once attached, the tracer emits gamma rays that are picked up by imaging.

The researchers used a cyclotron, a particle accelerator, in Carolina’s Biomedical Research Imaging Center to create Fluorine-18.

While the existing radiolabeling method requires the synthesis of dedicated new compounds to attach the radiotag, researchers say their approach may allow them to attach a tag existing compounds – a boon for drug development research.

“In this study, we showed that we could label a broad spectrum of compounds,” Li said, including for anti-inflammatory drugs, and specific amino acids to show that they could image tumors.

Researchers envision multiple potential applications for their discovery, including for medical imaging to screen patients for response to a drug, or to aid in drug development research.

“Not only can we study where drugs are localized in the body, which is something that’s important for drug development work, but we could also develop imaging agents to track cancer progression or inflammation in the body, aiding in cancer research and Alzheimer’s research,” Nicewicz said. “Having more than one method for tumor detection may give you cross-verification to make sure what you’re seeing is real. If you have two methods to validate a scan – two is better than one. Also, importantly, the information obtained by the new PET tracer could lead to corresponding treatment plan depending on the imaging result.”

The researchers said the next step is to develop a device that would make it easier for scientists to use this new method for creating radiolabeled tracers. In addition, they are working to expand their technology to develop other tracers that use a different radioactive material, such as Carbon-11.

“This discovery opens a new window for generating novel PET agents from existing drugs,” Li said. “Many very complicated, or almost impossible to label drugs, could potentially work using this method.”