Prepping for spring semester testing

“Forget what you’ve heard about nasal collection,” says UNC School of Medicine’s Amir Barzin about Carolina’s spring semester testing program. These tests are not brain ticklers.

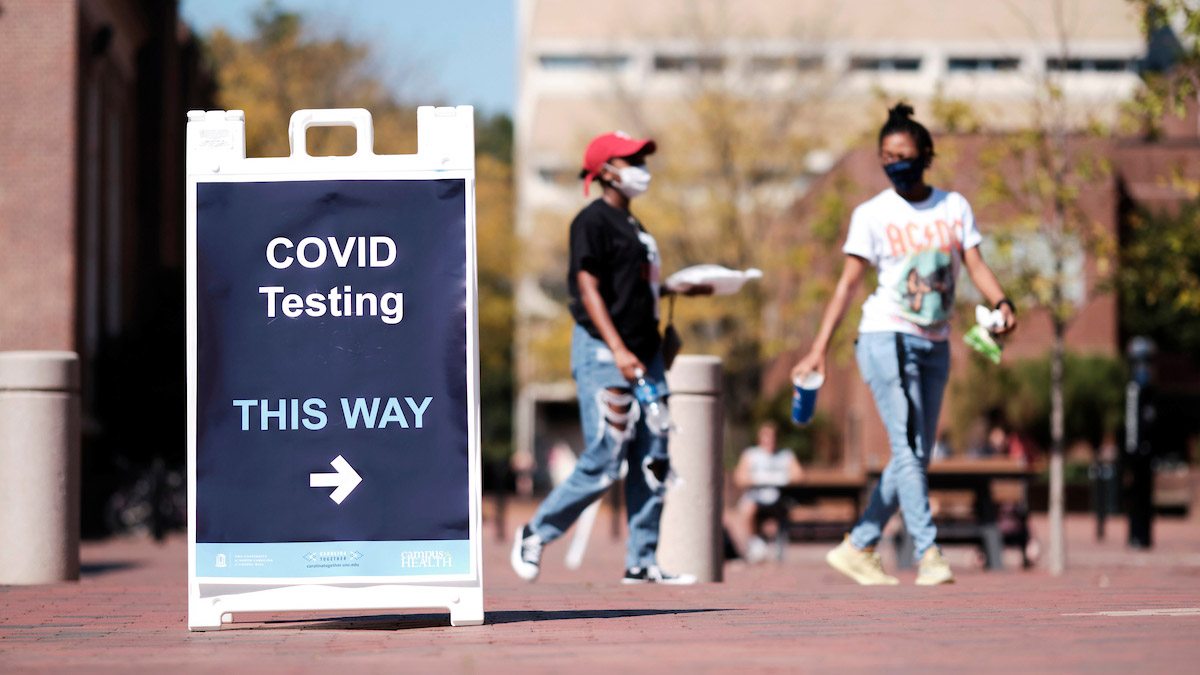

COVID-19 testing on campus is not new. The University began asymptomatic evaluation testing in September by offering saliva-based testing at the Carolina Union. But spring testing will be far more extensive — and required for many undergraduates as part of the Carolina Together Testing Program.

The University is creating three campus testing centers and also developing its own processing lab in the Genome Sciences Building to speed up results turnaround.

For more details about next semester’s testing program, The Well spoke with the UNC School of Medicine Assistant Professor Amir Barzin, medical director for the UNC Family Medicine Center. Earlier this year, Barzin helped UNC Health establish respiratory diagnostic centers across the state to conduct COVID-19 testing.

Now, he’s helping develop the Carolina Together Testing Program on campus, and answered a few questions on the process.

Beginning in January, the University is requiring many undergraduate students to get tested at home before returning to their dorms or off-campus housing. Why is prior-to-arrival testing important, and how does it work?

If you have a finite number of people living in an area, you want to start off with the best chance possible to succeed. A great example of this is what they did with the NBA. They decided to move to a central location. They tested everybody before they got there and limited interactions once there. And then they did regular interval testing throughout.

We want everyone coming back to our community to feel safe and comfortable, too. We don’t want someone to move back into the area, have a positive test and then worry whether they should be at home with their family or stay on campus. That’s what a prior-to-arrival test allows us to do. We’ll be trying to locate those positive cases that are out there and work with the local communities and health departments to give guidance on when it is appropriate to come back to the campus.

Then, when the students come back to campus after their period of isolation is over, they’re ready to hit the ground running. They’re here to be students. It’s meant to make it as simple as possible for students to be here, stay here and succeed while they’re here.

The second part of the Carolina Together Testing Program is asymptomatic evaluation testing at regular intervals. Why is that important, and how does that work?

The most important thing to remember about a test is it’s a snapshot. It’s a picture in time. You can have a negative test on Jan. 12. But if on Jan. 22 you have a runny nose or you’ve had contact with someone who tested positive, then the test on Jan. 12 doesn’t carry over.

We’re requiring all undergraduate students living on campus to be tested twice a week and those living in Chapel Hill or Carrboro to get tested once a week. Undergraduates coming to campus but not living in Chapel Hill or Carrboro will need to get tested, too. Graduate students accessing campus or living with more than 10 people will also participate in regular testing. Testing for other graduate students and for employees working on campus will be available but voluntary.

This interval testing gives us many more snapshots, far more data to use in making decisions.

We want to normalize getting tested. We’re in the middle of a pandemic — a once in a hundred years pandemic. We don’t want people to feel bad for getting a test. We don’t want them to worry about talking to the health department. This is all part of how we’re growing and learning as a society.

This is our commitment to our students, but it’s also our commitment to our community, to make sure that we’re keeping everyone as safe as possible.

We’re building this testing program because we want people to feel safe. But we also don’t want them to worry about infecting others in the community if they are asymptomatic carriers. That’s what regular interval testing lets us do. It doesn’t 100% stop transmission, but if we have fast turnaround time for our tests, and if we start seeing an increase in cases, we can quickly address the situation.

We have seen this work here at Carolina and know our students want to participate. Our Campus Health colleagues conducted more than 6,500 asymptomatic tests over the last two weeks of the semester as part of our exit testing program before our students left campus for the winter break. This was an astounding effort by that team, and we had a very low positivity rate.

The University will be using a nasal test rather than saliva test. Describe the test and explain the choice.

First, I would say to people: “Forget what you’ve heard about nasal collection.” This is not a nasopharyngeal swab — what some people call the “brain tickler” — that goes deep into the nose. Those require a health professional to administer. They’re uncomfortable. They’re not something that we want to do on a regular basis.

The test we will be using next semester is the anterior nasal collection swab. “Anterior nasal” means “front of the nose.” It’s self-administered and painless. The swab is like a Q-tip that you swirl around each nostril — 10 to 15 seconds per side, no more than an inch into the nose. So within 30 seconds, you’re basically done.

Why not continue with the saliva tests?

The saliva test has a lot of benefits, but it’s also a lot harder to implement and get an accurate result. For example, you’re not supposed to eat or drink 30 minutes before doing a saliva-based test. And it might take up to two to three minutes to work up enough saliva for a proper sample.

We are hoping to get best of both worlds here — a highly accurate PCR test that’s painless, fast and easy to administer.

Walk us through the testing process.

A lot of this is going to be self-directed. We’re developing what we’re calling Hall Pass, a digital, web-based application that allows you to walk into a testing station, take a picture of a barcode on a test kit and administer your own test.

You walk in, grab a Ziploc-like bag from a bin and take a picture of the barcode with your smartphone. Inside the bag is a vial with a nasal swab. You swab your nose, put the swab into the vial, put the vial back in the bag and drop the bag in another bin. Done. Our goal is that you’re in and out in less than two minutes. We don’t want students or employees to have to wait. We want to be very cautious and conscious of the number of people in the space at any given point. And we don’t want long queues outside either. We don’t want to promote any type of congregation.

It’ll take time for people to feel comfortable with the process, but we’ll have staff there to help guide them through. And the on-site staff will collect the samples and put them into coolers, which get sent to the lab.

Will there be enough testing materials available?

That has been my life for the past few months! We particularly like this type of test, and one reason is that the supply chain is secure. So, yes, I feel very, very good knowing that we have a thorough supply chain to be able to last through the semester and beyond if necessary.

What do you hope to gain from a rigorous testing program like this?

We want to safely bring students who need to be on campus back to campus. I feel for those performing arts degrees. I feel for those students who are science majors that need to be in laboratory spaces because that’s what they need to graduate from the programs. We’re trying to adapt as much as we can to limit the disruption for student learning and graduation. That’s what I believe this testing program gives us. It gives us the ability to do it in as safe a way as possible for both the students and the community. And if we see an increase in positive cases, it will allow us to hopefully limit any larger outbreaks. We have an obligation to make sure that they are healthy and safe and learning, and that’s what we want to try to fulfill.