Trio digs for clues to how the dead once lived

Carolina’s Research Laboratories of Archaeology turns 75 this year.

To get your hands dirty.

The expression may hold other meanings in other places, but at Carolina’s Research Laboratories of Archaeology, it means immersing yourself in every aspect of the job, including those parts that some would consider exhausting, backbreaking work.

Like digging in the dirt.

Steve Davis looks through sifted dirt for artifacts at the site of a 15th century Indian village near Hillsborough.

The three men who work here — Vin Steponaitis, Steve Davis Jr. and Brett Riggs — see all that digging as a special form of gritty detective work. Buried beneath all that dirt are clues that can reveal something new about how the dead once lived.

Riggs has been searching for answers since he was a boy back on his family’s 60-acre tobacco farm where he often stumbled upon an artifact out in the fields.

“This material was obviously evidence of people we can no longer see,” he said, “and it presented a mystery with so many unanswered questions: Who were these people? What were they doing? Why were they here? Why aren’t there still here?”

Those same questions, he said, still drive his work today.

A Treasure Trove of History

The three men have devoted the bulk of their professional lives to the lab, which turns 75 this year. The team measures their achievements not only in the scholarly papers they have produced, but in the number of skilled students they have mentored who will one day fill their shoes.

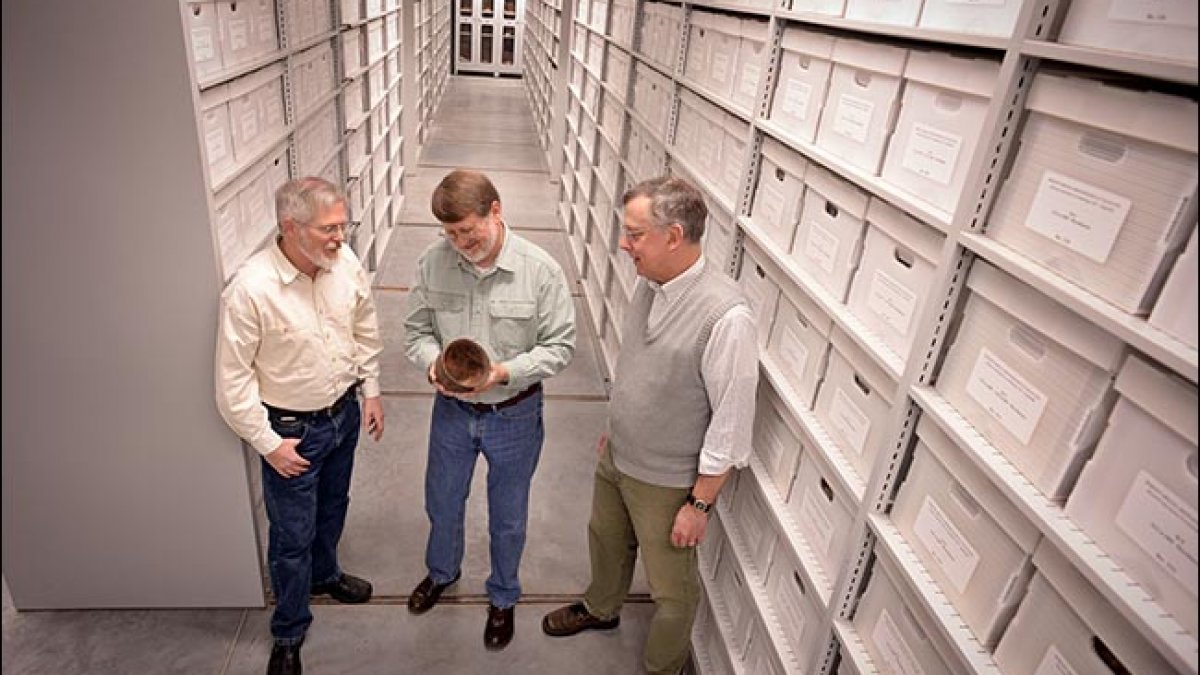

The enormity of their work shows in the 3,200 square-foot basement of Hamilton Hall, in the endless rows of bins stacked to the ceiling that make up the North Carolina Archaeological Collection. The collection holds more than 8 million catalogued artifacts documenting the history of Indian cultures in North Carolina and surrounding regions over 12,000 years – the most important collection of Cherokee and Catawba Indian artifacts anywhere.

When Steponaitis took over as director of the lab in January 1988, he was astounded to find the collections in an old warehouse in Durham.

The collection was stored all over campus as well – from the basement of Steele Building to under the steps of Wilson Library – before the RLA received a $450,000 federal grant in 2003 that helped put the collection in its permanent home in Hamilton.

Incoming first-year student Sarah Mitchell washes items retrieved from sites in preparation for cataloging

Since then, the RLA has become home to the Curriculum in Archaeology in the College of Arts and Sciences, which has made it possible for the RLA to support archaeologicalresearch throughout the world, including Europe, Latin America and the Middle East.

And earlier this year, partnering with University Library, the RLA launched the first online search tool for the North Carolina Archaeological Collection and placed more than 40,000 digital images in the Carolina Digital Repository. These innovations now allow the RLA to share its collections with scholars around the world, Steponaitis said.

Encountering Joffre Coe

Like Riggs, Davis’ fascination with archaeology traces back to his North Carolina boyhood, to a class field trip the summer after fifth grade to the Town Creek Indian Mound.

The mound, located near Mount Gilead in Montgomery County, served as the ceremonial center and village built by people of the Pee Dee culture who thrived in the Carolinas between 1150 and 1400 AD. The mound was actually a series of temples, one built atop another, that faced a large ceremonial plaza encircled by mortuary houses.

In charge of the excavation was Joffre Coe, the man who dominated the state’s archaeological endeavors for more than 40 years and who retired as director of the RLA in 1982. A year after Coe’s retirement, Davis arrived to undertake what would become a 30-year project studying native peoples throughout NorthCarolina’s Piedmont.

Riggs joined the RLA in 2001 after working for the Eastern Bank of Cherokee Indians, a federally recognized native nation located in western North Carolina.

The expertise of Riggs and Davis encompassed the entire state, said Steponaitis, whose own research spans the South to include the Natchez Indians, among the last American Indian groups to inhabit southwestern Mississippi.

Through the years, Davis has come to appreciate he can connect more of the dots with colleagues like Riggs and Steponaitis than he ever could have alone.

“The nature of archaeological research is difficult. It’s tedious and it’s slow,” Davis said. “To make major advances in understanding requires the strong dose of collaboration we’ve always had here.”

The work has alsobeen made easier by the fact they enjoy each other’s company, Steponaitis added. “The collaboration and the collegiality is what makes it so much fun,” Steponaitis said. “It is also why we get so much done.”

Coming full circle

They know that the partnership they have forged will one day come to an end, but they are determined to push that day off for as long as they can.

Davis, the oldest at 63, is determined to keep going until he reaches 70. Steponaitis, at 61, is “vaguely thinking 70” as well. Riggs, the youngest at 57, said, “I’m looking at 10 more years.”

This year, though, theyare taking time to celebrate all that has been accomplished along with the descendants of the out various tribes they have studied.

Like the Europeans who arrived in American centuries ago, they are newcomers, and because of the very nature of their work, intruders as well. It is important to remember that, Riggs said.

“We are dealing with a sensitive topic,” Riggs said. “We have communities of people who have deep histories and distinctive identities intimately tied to those histories. Archaeology is atool and it is really up to us how we use that tool, whether we reveal that history for us, or for them.”

That is why, Steponaitis said, the North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs is planning to meet on campus in early June to join in the RLA’s celebration. They have also been invited to visit the field school that the RLA conducts with students every summer that allows them to learn the techniques of archaeology by helping to excavate a site.

This year, the school will be held onthe Wall site on the Eno River at Hillsborough that was occupied just before the attempted English settlement of North Carolina’s coast in the 1580s. Not far from the Wall was a village of the Occaneechi band dating back to 1700.

These sites hold a special place in the history of the RLA as well. In the summer of 1940, founding director Robert Wauchope led the RLA’s first excavation there. The summer Steponaitis took over as director in 1988, he participated in a field school at the site.

The reason they return to these sites again and again is because old questions always beckon to be asked anew.

And it is why, Davis said, the digging never gets old – “it only gets deeper.”