A creek runs through it

Water springing from a granite ridge millions of years in the making is a main reason for Carolina’s location. Here’s a look at how that water flowing under and through campus becomes the University’s Meeting of the Waters Creek.

If you’re on campus and lucky, you can hear or, better yet, see the water.

The water flowed down the granite ridge on which Carolina sits long before New Hope Chapel was chosen as the site for the University in 1792.

The flow was the main reason for the University’s location, founder William Richardson Davie wrote in 1793.

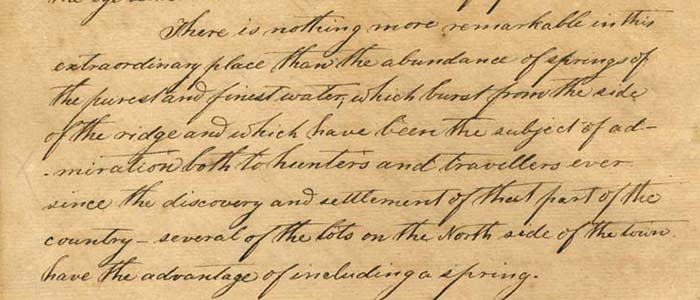

“There is nothing more remarkable in this extraordinary place than the abundance of springs of the purest and finest water, which burst from the side of the ridge, and which have been the subject of admiration both to hunters and travelers ever since the discovery and settlement of that part of the country … ”

William R. Davie’s handwritten description of the “abundance of springs of the purest and finest water, which burst from the side of the ridge … ” (© Copyright 2005 by the University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, all rights reserved.)

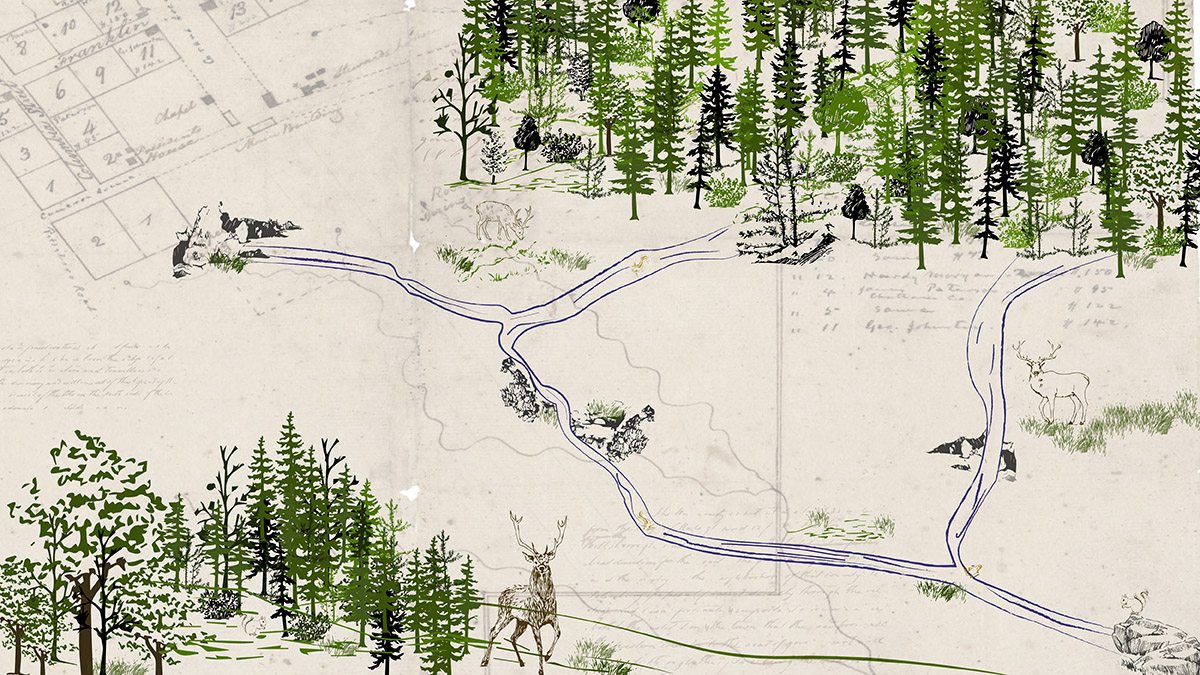

Today, water still flows, but the University’s buildings and roads cover much of it. The springs combine with smaller branch lines and stormwater runoff from 200 acres at the heart of campus to form Meeting of the Waters Creek on Carolina’s southeast side. The creek’s sources drain from a watershed that roughly parallels Pittsboro Street to the west, along Cameron Avenue to the north and down Ridge Road to the east. It is home to amphibians such as salamanders and frogs, invertebrate life-forms and, after it makes final outfall on its way east, hundreds of fish.

Where it begins

Maps dating to the University’s earliest years show many springs, with at least two located south of the present-day Carolina Inn. Those springs feed the Chapel Branch stream, which still flows under Morehead Labs and along Raleigh Road to daylight in Coker Woods, a vine-snarled patch of hardwoods in front of the Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History. There, it joins water coming from the north.

A 1792 map by surveyor John Daniel shows at least three springs near the inn property with flow lines leading southeast. Archibald Henderson’s 1949 book “The Campus of the First State University” confirms the springs’ location where the inn was built. It describes a dilapidated chapel standing near the southwest corner of the crossroads inn. “Near the Chapel of Ease was a spring of considerable size, known as Chapel Spring, from which flowed the stream which winds its way through picturesque scenery, by the Meeting of the Waters to Morgan’s Creek at Scott’s Hole on the Mason plantation.”

A map titled “Plan of the Village at the University” drawn sometime between 1797 and 1812 also shows three springs, including Chapel Spring, and Rock Spring near Pittsboro Road (now Pittsboro Street), which also supplied the Chapel Branch. In the ensuing decades, springs in the vicinity of the Carolina Inn, Whitehead Hall and the FedEx Global Education Center were covered by construction, but the groundwater beneath the buildings still drains downhill, possibly finding new outlets and feeding Meeting of the Waters Creek.

How the creek was named

American Indians had probably named all the local water sources, and settlers began giving them names. By the late 1800s, area springs and branches all had English names, but the stream formed by their combined flows had no name for maps until Carolina’s eighth president, Kemp P. Battle, came along. Known for hiking and making trails, Battle was a Tar Heel student and then a tutor from 1845 to 1854, long before becoming the University’s president in 1876. His forays into the forest perfectly matched his well-documented proclivity to name places.

In the first use of “Meeting of the Waters” in print, Battle described the path to the creek in the 1897 “Yackety Yack” yearbook. Later, he updated that passage in his “History of the University of North Carolina, Volume II: From 1868 to 1912,” with directions to a particularly lovely setting that’s most likely southeast of Boshamer Stadium.

There, he writes:

“ … the pedestrian will reach a most romantic spot, the ‘Meeting of the Waters,’ where Chapel Branch and Rockspring, or Brickyard, Branch come together among numerous gray rocks. The dense shade of the lofty trees, the musical murmur of the tumbling streams, the high bluffs covered with mosses and ferns, hepaticas and heart leaves, the rustling of the leaves of the treetops, and the perfect calm below, make this an ideal place for lovers of Nature.”

The Brickyard Branch that Battle mentions probably trickled from the area today called “Battle Forest,” where men dug clay and fired bricks during the University’s earliest years.

Walking up to campus along the creek, Battle notes “high bluffs, among heart leaves, anemones, ferns, stellarias, tiarellas, irises, and other beautiful plants. Lofty beeches, their bark covered with the initials of students vainly seeking perpetual fame, overhang the ever-winding stream and give a grateful shade at all hours of the day.”

Water from a rock

What Battle described had been millions of years in the making.

The area’s granite formed 630 million years ago when this piece of crust was attached to South America, said Kevin Stewart, associate professor in the College of Arts & Sciences’ earth, marine and environmental sciences department. After that area broke away to form North America, a fault developed about 200 million years ago as the continent of Africa pushed away to open up the Atlantic Ocean. That split made the granite more prominent, forming the escarpment or long ridge on which Carolina sits.

“The fault here was a ‘failed’ rift,” Stewart said. “The crust faulted and created an escarpment, but the rift that eventually became the Atlantic Ocean was far to the east, so we never had waterfront property, just a narrow rift valley that filled in with sediment.”

As the granite developed cracks, water soaked in and percolated back up thousands of feet in the form of springs. Those springs eventually carved out streams. The same thing happens today.

“It’s a reasonable speculation that those springs follow cracks in the rock that were generated when that fault was active about 200 million years ago,” Stewart said. “We’re getting water from a rock.”

Follow the creek

A good imagination helps in following the creek from its origins shown on the earliest maps. Even better, learn about it from someone like Janet Clarke, stormwater specialist with Carolina’s Environment, Health and Safety office. Clarke’s primary job is controlling sediment and erosion from construction sites on campus. She monitors the health of streams by checking the water quality and handles pollution prevention.

Jamie Smedsmo, a water engineer in Energy Services, sometimes takes classes studying watershed planning and ecology along the path of Meeting of the Waters Creek. According to Smedsmo, today’s creek starts under the parking lot behind Morehead Labs and flows underground on the north side of Raleigh Road before discharging into Coker Woods. Water from two pipes on the northeast corner of the woods flows through a few yards of stream before disappearing again into pipes. Biology and geography classes have sometimes used the Coker Woods section as a field laboratory.

“There’s always a base flow. It’s never dry,” Smedsmo said.

Behind the Stone Center, one of dozens of catch basins around campus sits underground, blending into the landscaping and regulating stormwater runoff into the stream.

The water continues under Kenan Stadium, where in 1927, workers channeled the Chapel Branch. In those days, two bridges on the stadium’s northwest side enabled fans to cross the stream in their model-T’s. Just past the stadium, the grassy top of Rams Head Parking Deck filters rainwater for use in irrigation, with overflow joining water funneling from the northeast side of campus.

A short walk from Boshamer Stadium’s outfield, the combined water from 200 acres of campus emerges to form the mile-long Meeting of the Waters Creek. It cascades through Coker Pinetum, under highway 15-501 and past the North Carolina Botanical Garden, eventually finding its way to the Cape Fear River and the Atlantic Ocean.

Water from springs, streams and stormwater runoff forms Meeting of the Waters Creek, which flows through the Coker Pinetum on the southeast side of campus and on to the Atlantic Ocean. (Jon Gardiner/UNC-Chapel Hill)

Taking care of the creek

The creek’s health concerns Clarke, who said that after a large rainfall, the water “can be soapy, milky, even scummy, depending on what’s going on upstream.”

When monitoring the stream every month or two, Clarke checks six main outfall locations. If she notices things such as soap bubbles or a change in color, she tracks it to the source. “Anything on the ground could wind up in a storm drain — balloons, paint, construction debris and erosion from construction,” she said. Paint, sidewalk chalk dust, dye and sudsy residue of mobile car washes are among the things Clarke has found. “I’ll talk with whoever is doing it and hope that it doesn’t happen again.”

Clarke also protects the creek’s health by wearing a hard hat on walk-throughs with construction site managers for companies working on campus. She makes sure that erosion control measures are preventing mud from running into the creek. EHS also conducts stormwater awareness training for workers from Grounds, Facilities Services, Energy Services and construction crews. And EHS communicates with students and departments that host events, pointing them to the EHS website’s information on avoiding pollution.

The ways in which the University has treated water and streams on campus parallels how American civilization in general has dealt with water over time, according to Smedsmo. Water management evolved from a philosophy of using pipes and engineered structures to quickly convey water off campus to green infrastructure that holds, treats and filters runoff at its source.

With those efforts by the University and our personal efforts, Meeting of the Waters Creek will continue flowing for generations to come.