Archiving community stories

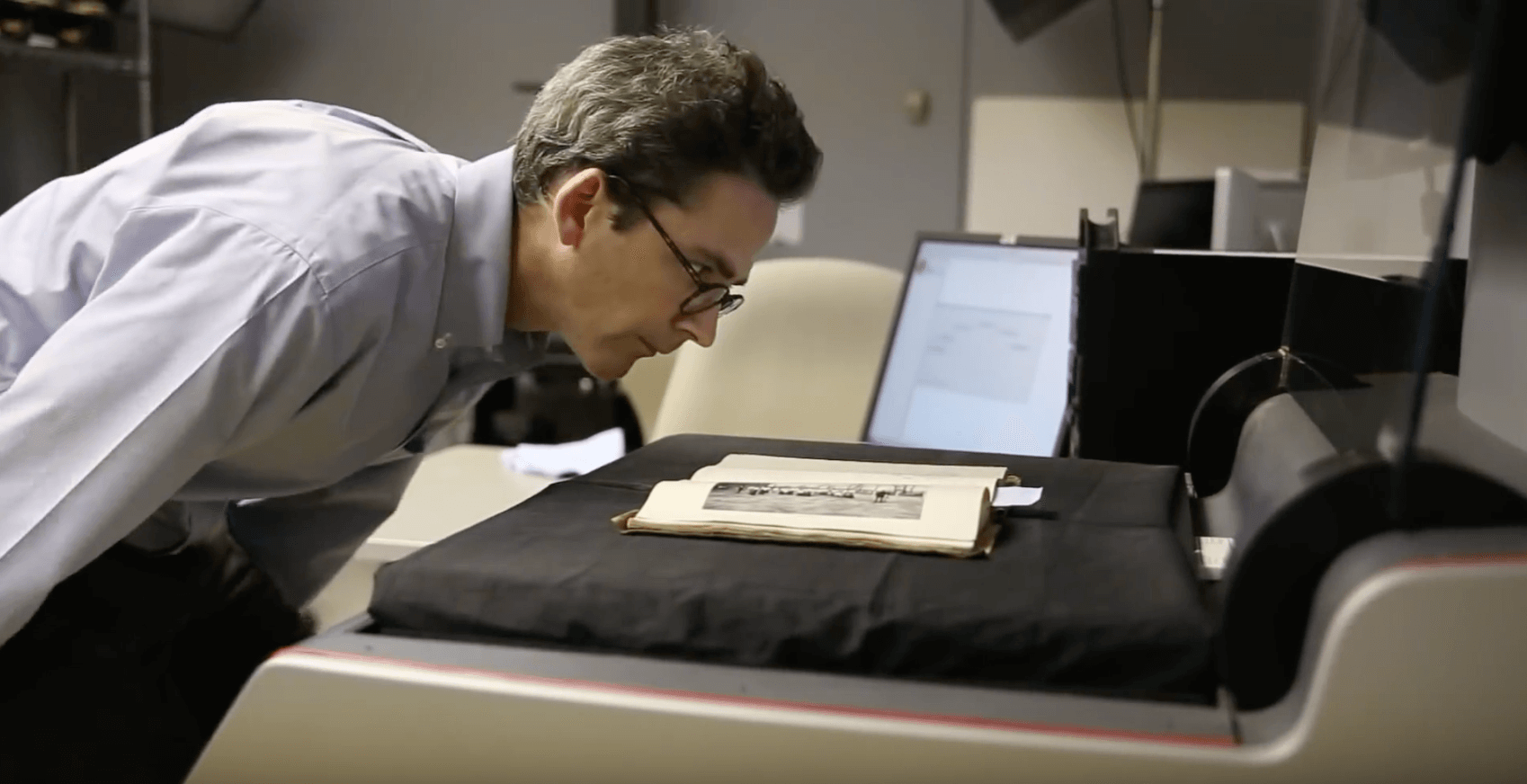

Carolina's Archivist in a Backpack project, a project of the University Libraries, is empowering everyday people to tell their own stories and capture the history of communities around the world.

Every community has a story, and every tool needed to document them can fit into a single backpack.

That’s the approach behind the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Archivist in a Backpack project, which empowers communities to tell their own stories.

“The question we raised was, ‘What can we do that gives people the tools to take ownership over their history?’” said Bryan Giemza, director of the Southern Historical Collection (SHC) at the University Libraries. The SHC originated and manages Archivist in a Backpack. “There’s a deep dignity and respect that comes from understanding one’s own history and having a personal stake in it.”

Archivist in a Backpack provides community partners with bags filled with easy-to-use recording equipment, notepads, sample interview prompts and other home archiving tools to help everyday people record local narratives on the go.

With financial support from the Mellon Foundation in 2017, the backpacks have traveled across the country and captured stories ranging from community health initiatives in rural Appalachia to the African-American experience in San Antonio, Texas.

Now, the backpacks are crossing international borders.

This fall, they will be traveling to Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula to help communities uncover the stories, legends and sacred meanings behind cenotes — underground pools of turquoise water that are living artifacts of Yucatán Maya heritage.

Patricia McAnany, an anthropology professor at Carolina and a Maya archaeologist who has conducted field research and cultural heritage programs in the region, is empowering middle school students in Yucatán to collect the stories that surround the country’s cenotes, from their role in ancient Mayan rituals to their use on the peninsula today.

As part of a National Geographic grant, the students will use portable recorders to interview elders in their communities, as well as others who are knowledgeable about cenotes.

“Cenotes for the Maya have always been associated with spirits and supernatural forces and this life-giving essence of rainmaking,” said Dylan Clark, project manager for the Yucatán activity. “People have been relying on these underground fresh water sources for centuries. So we wanted to help teachers complement their course materials with different experiential learning components that would really hook the students and get them excited about their local cenotes.”

McAnany believes the oral history project will bridge a generational divide by engaging young people in cultural and environmental preservation.

“The conservation of cenotes is really critical to the cultural heritage of Yucatán in general,” she said. “I think the community is aware that they have something very precious there, and we want to keep it that way.”

Clark said he hopes the project preserves both the heritage and the ecology of cenotes, which are at risk of contamination from trash and other pollutants.

“The students are super jazzed about the folklore and the rituals and all sorts of things,” Clark said. “It’s a way of fostering a consciousness of conservation and allowing them to reconnect with their heritage.”

For Giemza, seeing the initiative reach beyond the American South is a highlight of the project.

“It’s pretty stunning to see, ‘Oh, those are our backpacks,’ and ‘Oh my goodness, this is translated into Maya language,’” he said. “It’s really energizing. When we talk about archiving, the more people who are involved, the more voices and perspectives that we have, the richer the record we’ll be able to produce.”

To follow along with their project, visit National Geographic’s OpenExplorer.