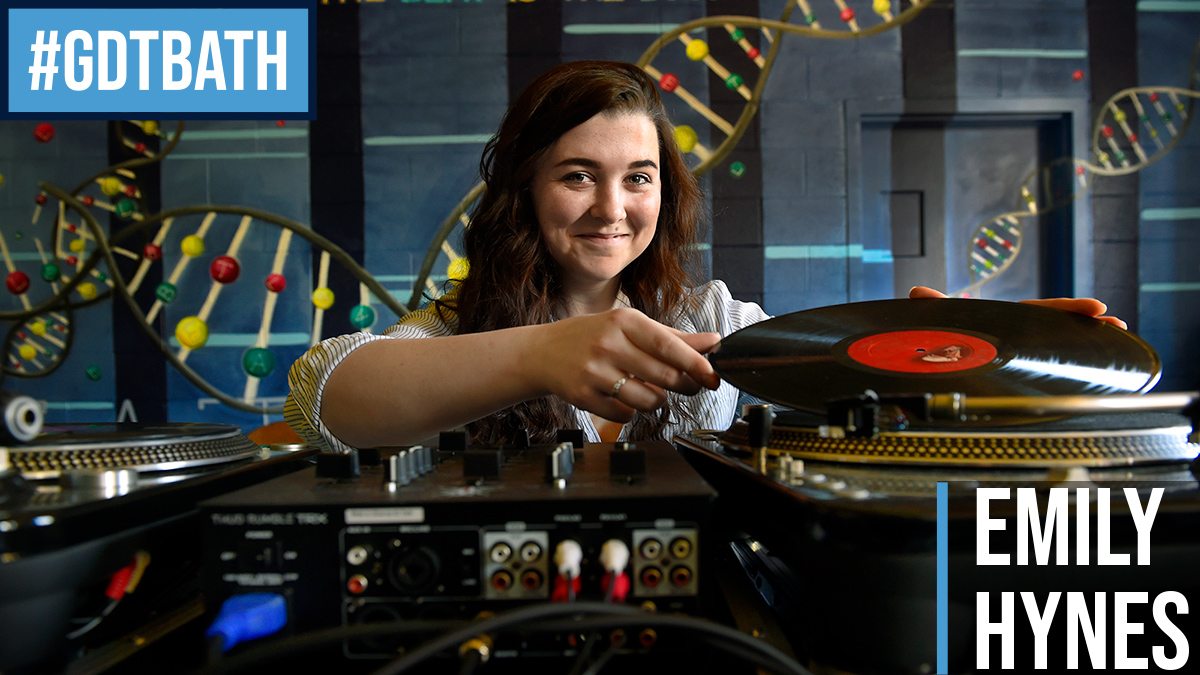

#GDTBATH: Emily Hynes

Graduate student Emily Hynes is using digital humanities tools to examine musical recordings from the American South to bring the true stories of the recordings to light.

Emily Hynes is examining musical recordings made in prisons in the American South before World War II and is creating digital maps that she hopes more accurately capture the stories of the inmates and their music.

Hynes came to Carolina because of the progressive and rigorous musicology program and the opportunity to be a member of The Graduate School’s Royster Society of Fellows.

“The fellowship has offered me unique research and networking opportunities,” she said.

Last year, one such research opportunity came her way through the James W. Pruett Summer Research Fellowship awarded through the music department. Hynes conducted research at the Library of Congress’ American Folklife Center, which includes the field recordings and books of John Lomax, a pioneering musicologist and folklorist. Like other folklorists of his generation, Lomax traveled the country collecting songs from prison inmates. Lomax would visit prisons across the South, gather the inmates together and record them.

As Hynes recounted, “some of the songs were folk songs, some of them were slave songs and some of them were Appalachian songs that were appropriated into the slave culture.”

Hynes is now working to create digital maps of these recordings. Musicologists use geographical maps in combination with digital humanities tools to convey the movement of music and musicians as well as to contextualize music history within broader social, cultural and political history. Mapping one’s research findings in an ethical way, however, means taking into consideration such characteristics as the power dynamics at play during the time of the initial recordings.

“The title and content of the maps needs to highlight the prisoners’ names and any information we have on them, rather than putting it all under the umbrella of ‘Lomax’s Recordings’ and only showing what he thought was relevant to know about them,” Hynes explained.

Hynes’ research turned up conflicting representations of songs and conversations in Lomax’s notes. In one instance, when she listened to the recording to try to understand a particular contradiction, she found that Lomax had embellished the story and dialect of a prisoner and even called him a racially insensitive name.

“Now the project has really become me wanting to look at these recordings and the way they were notated and published, and finding places where there are discrepancies,” Hynes said, “and in some cases, discrepancies that show instances of racism or sexism.”

After finishing her master’s thesis this spring, she will begin work on her Ph.D. and has decided to focus on women’s prison music because so little scholarship exists on the topic. This past summer she was surprised to find in the Library of Congress nearly 70 women’s prison music recordings from four Southern women’s prisons. It strengthened her resolve to bring these neglected stories to light.

Hynes grew up in rural Minnesota, which may sound far removed from the songs of the South that she studies, but she said she finds it easy to discuss the country and folk melodies with her family. The fact that many of Hynes’ older family members grew up with these songs speaks to the pervasiveness of folklorists’ canonization of folk songs in the 20th century.

Hynes hopes that her research will touch real people’s lives and extend beyond the academy.

“I want people to be able to go to a website, look at the maps, listen to all of these different recordings and see if there’s a connection there,” she said. “I think that the subjects of musicological study don’t have to be people who were necessarily famous — these people still contributed to history.”