Jim Thorpe’s Olympic wins restored — 110 years later

The Native American athlete’s story, which hinges on two summers in North Carolina, reminds us to reassess whom to “villainize and valorize,” says sports historian Matt Andrews.

More than a century ago, events from two summers in North Carolina led the International Olympic Committee to strip two gold medals from Native American athlete Jim Thorpe. On July 15, nearly 70 years after his death, the IOC renamed Thorpe the sole winner of the 1912 Olympic decathlon and pentathlon.

To learn more about Thorpe’s background, athletic prowess and what led to the stripping and reinstatement of his Olympic victories, The Well spoke to Matt Andrews, teaching associate professor in the College of Arts and Sciences’ history department, who specializes in the link between sports and American culture.

Thorpe, who belonged to the Sac and Fox Nation, grew up in Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma. When Thorpe was 16, his father sent him to Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania.

Andrews described Carlisle as a school “created and run by white philanthropists who believed that Native Americans needed to be stripped of their culture and assimilate with dominant white culture in the United States.” He said the motto at Carlisle was “Kill the Indian and save the man.” At this school, Native American students were taught English, “proper table manners” and sports like baseball and football.

Thorpe excelled in each sport he played. Gifted in lacrosse, a sport with Native American origins, baseball and track, Thorpe made a name for himself in college football.

In 1911, Carlisle Indian School defeated football powerhouse Harvard University. People began to take notice of Thorpe, the star of the team, Andrews said.

The promise and problem of diversity

At the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm, Thorpe, who joined the U.S. team, blew away the competition in the pentathlon, made up of five track and field events, and the 10-event decathlon.

In the decathlon, he scored 8,413 out of a possible 10,000 — 688 points higher than the next-place finisher, Swedish athlete Hugo Wieslander.

Andrews said the U.S. Olympic team returned to a ticker-tape parade in New York City and Thorpe got the loudest cheer.

The 1912 team, he said, featured African Americans, Hawaiians, like the great swimmer Duke Kahanamoku, and Irish Americans who had immigrated to the U.S.

“A lot of people held up Thorpe as a representative of the promise of diversity in the United States,” said Andrews. “There were also some, though, who found that diversity problematic.”

Native Americans did not become U.S. citizens until President Calvin Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924. Kahanamoku was a native of the Polynesian archipelago of Hawaii, which didn’t become a U.S. state until 1959. Female athletes represented the U.S. at the Olympic Games before they earned the right to vote. The contradictions continued, with Jesse Owens representing the U.S. at the 1936 Berlin Olympics even though African Americans lacked basic civil rights in America.

“There’s obviously some level of hypocrisy going on there,” said Andrews. “The United States was, generally speaking, more than welcome to have great athletes of color represent them in international competition but then deny them full civil rights back at home.”

Back at home, Thorpe returned to the football field. During the fall of 1912, he led the Carlisle Indians to a stunning victory over the powerful Army program, whose star player was future WWII general and President Dwight David Eisenhower.

Thorpe’s luck changed in 1913, when news spread that the Olympic gold medalist earned money playing minor league baseball in Rocky Mount and Fayetteville, North Carolina, during two summers before the 1912 Games.

Olympic idea of ‘amateurism’

Until 1992, Olympic athletes had to be “amateurs.” But what did that mean? Andrews said amateurism meant any athlete who accepted money for playing a sport was barred from the Olympics.

In Thorpe’s day, many college athletes earned extra money, about $25 a week, playing minor league baseball. They used an alias to keep their amateur status. When Thorpe played baseball in North Carolina, he signed his own name.

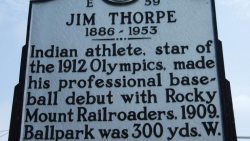

A historical marker in Rocky Mount indicates where Jim Thorpe played baseball prior to the 1912 Olympics. (NC Department of Natural and Cultural Resources)

The American Olympic Committee used this proof to strip Thorpe of his medals. The IOC removed his name from the record books. The man who had made history in the games did so again by becoming the first Olympic athlete to have his medals taken away.

Andrews said the quick condemnation of Thorpe lacked due process, one reason he calls the actions against him “somewhat illegal.” Thorpe’s violations also were not discovered until six months after the Olympics, well past the 60-day deadline for filing a letter of opposition according to the rules at the time.

“I have no doubt in my mind that if Jim Thorpe had been an upper-class white athlete from, say, Harvard or Princeton, that he would not have been sacrificed and chopped off in the way that he was,” said Andrews. “Had he technically broken the rules? Yes, but there are a lot of ways to defend Jim Thorpe back then and because he was Native American, because he was vulnerable, he was attacked.”

The decathlon second-place finisher, Sweden’s Wieslander, was bumped to first place and given the gold medal. Andrews says Wieslander always considered Thorpe the “real” victor in the decathlon.

Norway’s Ferdinand Bie, the pentathlon second-place finisher, was awarded the gold but never accepted.

A cloud over a remarkable athletic career

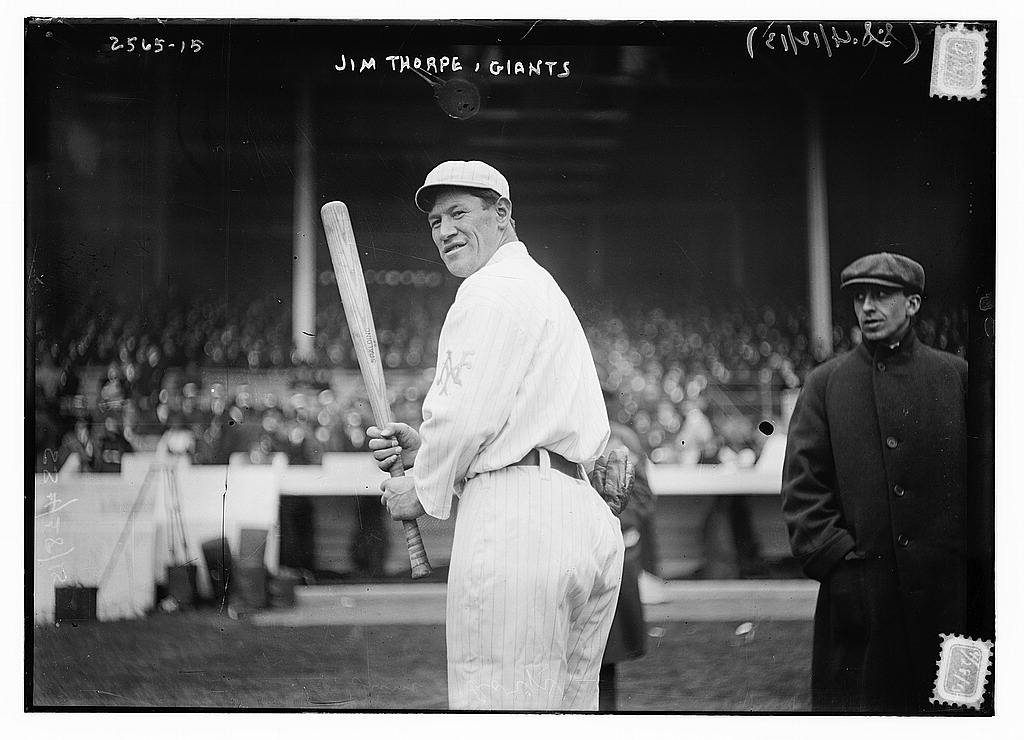

Following the scandal, Thorpe played Major League Baseball for the New York Giants from 1913 to 1919. In 1915, he joined the Canton Bulldogs, a professional football team in the Ohio League, and continued playing pro football as a new league emerged — the National Football League. Thorpe was elected the first president of the NFL when it was originally established as the American Professional Football Association in 1920.

Jim Thorpe playing for the New York Giants in 1913. (Library of Congress)

Though considered by many the greatest American athlete from the first half of the 20thcentury, Thorpe never escaped the cloud of 1912.

He retired from sports in 1928 and found bit parts in movies. Andrews said Thorpe died penniless in 1953 with the general narrative of him as “a great athlete, but someone who did not follow the rules, cheated the system or, at the very least, was unaware of the rules as he should have been.”

Righting a century-long wrong

In the 1980s, Andrews said the IOC began landing high-dollar sponsorship deals and began to understand the inherent hypocrisy of its amateurism rules for athletes. In 1992, the IOC allowed professional athletes to compete in the Olympic Games.

“The IOC is very reluctant to admit that they’ve ever made mistakes,” said Andrews.

In 1982, the IOC gave duplicate medals to Thorpe’s family but listed him as a co-champion in the record books.

On July 15, 2022,the 110th anniversary of Thorpe’s decathlon gold medal, the IOC announced that it would reinstate Thorpe as the sole winner of the 1912 Olympic pentathlon and decathlon.

“This does nothing for Jim Thorpe. Obviously, this does nothing for Jim Thorpe’s family members,” Andrews said. “They always knew what was right and what was wrong.”

But while some may consider the IOC’s action too little too late, reflecting on the past is “part of the larger push and thrust for social justice,” Andrews said.

“As a historian, I think it’s important to look back at the past, to once again revisit the people who we have chosen to villainize and to valorize and to reassess what they did and to reassess the way they were treated,” said Andrews.