Lineberger leads endometrial cancer moonshot

This vastly understudied uterine disease is on the rise, but Dr. Victoria Bae-Jump and others are fighting to turn the tide.

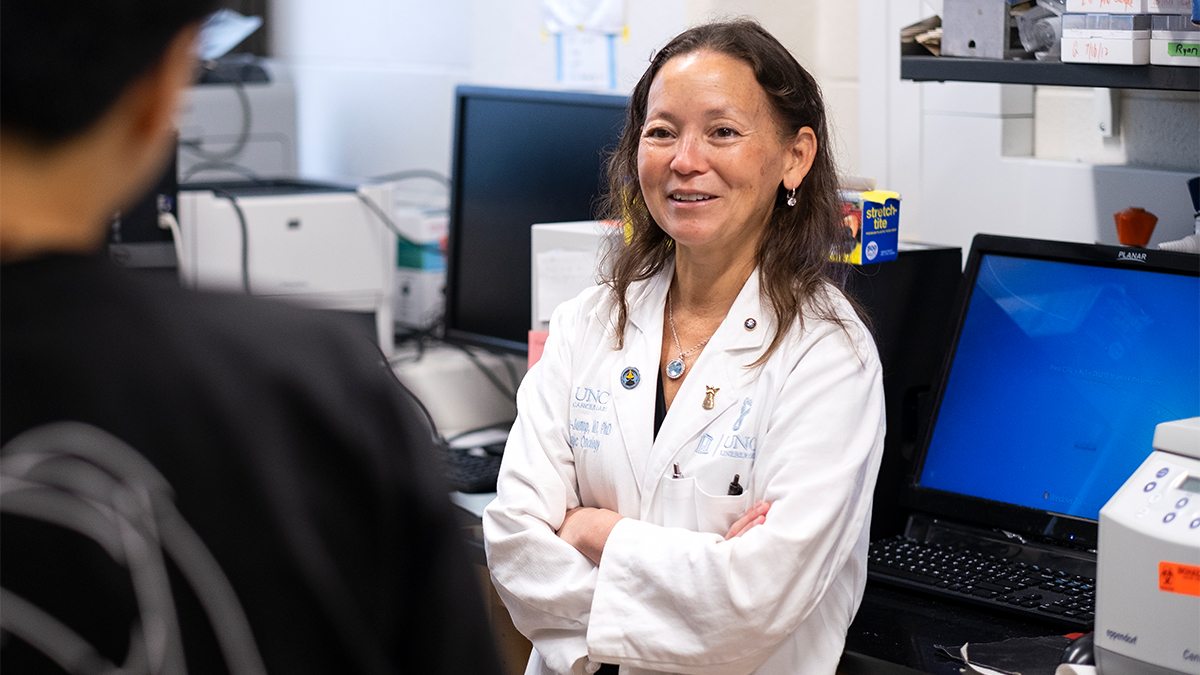

All cancers pose research mysteries. For Dr. Victoria Bae-Jump, endometrial cancer, which attacks the lining of the uterus, is especially puzzling — and troubling.

Why, she wants to know, does endometrial cancer kill Black women at twice the rate of white women, representing perhaps the largest racial disparity in all U.S. cancer outcomes? Why is it linked so closely with obesity — far more than any other cancer? And why is it the only major cancer that is increasing in both frequency and mortality?

These questions are more than academic for Bae-Jump. Along with running a research lab in the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, she is a gynecological oncologist with UNC Health. The patients she sees on a weekly basis are her fellow North Carolinians.

Endometrial cancer, which mainly affects post-menopausal women, is the most prevalent gynecologic cancer among American women, and it’s on the rise. By 2040, endometrial cancer is expected to displace colorectal cancer as the third most common cancer among women and the fourth leading cause of cancer death in women.

And yet, this enigmatic malignancy remains one of the least funded and least studied of the major cancers. Many women, unaware of endometrial cancer or its symptoms — most frequently abnormal vaginal bleeding, along with pelvic pain — don’t realize they have the disease until it has reached an advanced stage.

“For women with advanced disease, which is a good third of our patient population, it has always felt like I didn’t have much to offer,” Bae-Jump said.

She and her colleagues across the University are working to change that. Through the Endometrial Cancer Center of Excellence, launched in 2021, they are bringing to bear the vast resources and expertise of Carolina, a top-tier R-1 research institution, to study all facets of the disease and the people it impacts.

These and other efforts at UNC Lineberger — one of only 53 National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers — recently drew the attention of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. In February, its director, Arati Prabhakar, visited Lineberger to discuss how the work is contributing to the Biden-Harris Administration’s Cancer Moonshot to end cancer as we know it.

“Many universities are making progress in cancer research, but why is Carolina different?” asked Penny Gordon-Larsen, interim vice chancellor for research, in an article she penned following the visit. “Our culture of collaboration is what sets us apart.”

Launching a world-class study

To understand endometrial cancer and how to combat it, Bae-Jump and her colleagues needed better data.

Historically, “Black women do so much worse from endometrial cancer, and yet they’re completely underrepresented in clinical trials, as well as our molecular profiling studies,” Bae-Jump said. Not only are Black women proportionally more likely to get endometrial cancer, but “they’re more likely to get more aggressive molecular subtypes, including serous histology tumors and cancers with p53 mutations. We don’t really understand why all of that’s going on.”

To remedy the lack of representation, she and a team of researchers launched the first-of-its-kind Carolina Endometrial Cancer Study. Funded by Lineberger, the population study is modeled after Lineberger’s groundbreaking Carolina Breast Cancer Study, begun in 1993 and still churning out heaps of useful data as it enters its fourth phase.

Like the breast cancer study, this one is inclusive, racially diverse and focused on women in North Carolina. Its co-principal investigators are Andrew Olshan and Hazel Nichols, epidemiologists from the Gillings School of Global Public Health. They are leading the recruitment of up to 1,500 women diagnosed with the disease from all 100 of the state’s counties, including at least 500 Black women, which will be the largest cohort of Black women in a population-based study.

And they’ve made it patient-centered. At every stage, study leaders speak with representatives from a national advocacy group called the Endometrial Cancer Action Network for African Americans to review things like recruitment methods and study questions. “It’s not just about what the investigators think is important,” Nichols said. “It’s also bringing the questions that patients and survivors are dealing with every day.”

This study is remarkable for its transdisciplinary scope. Previous studies have more narrowly focused on, say, the molecular characteristics of tumors or certain types of therapies. Others have focused on patient-reported outcomes or epidemiological data about where people live, their social connections and other things that happen outside the lab and the hospital.

“For the Carolina Endometrial Cancer Study, our primary goal is to bring the strengths of each of these approaches together to have a more holistic picture,” Nichols said.

“The goal is to put together, for the first time for endometrial cancer, the social determinants of health and tumor biology and epidemiological factors,” Bae-Jump said. “If we can do that, then we can potentially figure out what would be the best interventions to move forward with.”

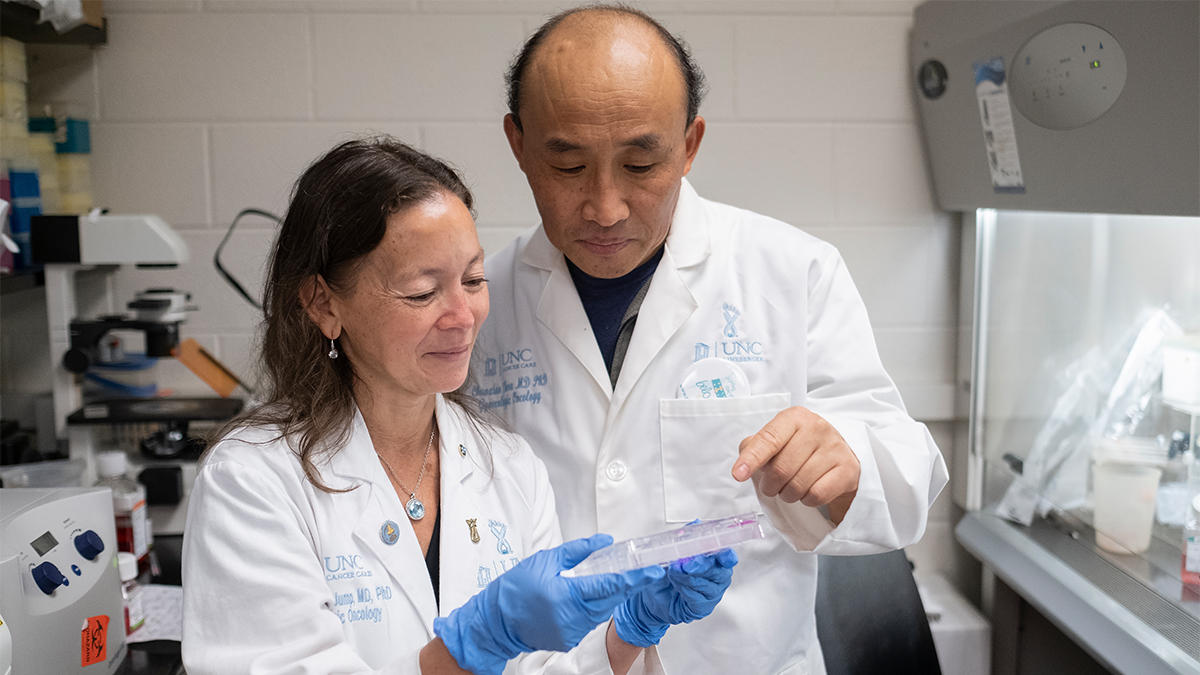

Bae-Jump and lab manager Chunxiao Zhou examine a cell culture. (Jon Gardiner/UNC-Chapel Hill)

Improving patient outcomes

In fitting with the holistic nature of the work being done by the center’s 50 investigators from 18 different departments, the possible interventions being studied are wide-ranging.

Bae-Jump herself is involved in a first-ever study to assess the microbiome — the collection of bacteria, fungi, viruses and other microbes that live on and in the human body — and its interrelationship to endometrial cancer.

Scientists know the gut microbiome affects biologic pathways for cancer, including how fast cancers progress and the efficacy and toxicity of treatments like chemotherapy and immunotherapy. But what about the uterine microbiome? Are there racial differences in the uterine and gut microbiome? And how can we manipulate the microbiome to improve cancer treatment? These are some of the questions she hopes to answer.

And then there’s the obesity link. In general, obesity is thought to account for less than 8% of cancer cases. For endometrial cancer, however, obesity is thought to drive more than 60% of cases. How? Obesity leads to the upregulation of a number of pathways, including insulin pathways and the mTOR pathway, which can drive tumor-causing mutations, Bae-Jump said. In obese women, estrogen levels in the uterus increase, another direct link to endometrial cancer.

“Many cancers are a random act of violence, but obesity is a modifiable risk factor,” she said.

Therefore, Bae-Jump and her colleagues are studying interventions to break the obesity-endometrial cancer link. One study is looking at whether a promising new weight-loss drug, Tirzepatide, can decrease tumor growth. And if so, how? Does it take away growth factors that could be fueling tumors? Or does it directly affect tumors themselves through insulin and GLP-1 pathways?

Another study looks at the effects of intermittent fasting on endometrial cancer and, so far at least, seems to show that intermittent fasting is far superior to other diet manipulations, like shifting from a high- to low-fat diet and even bariatric surgery.

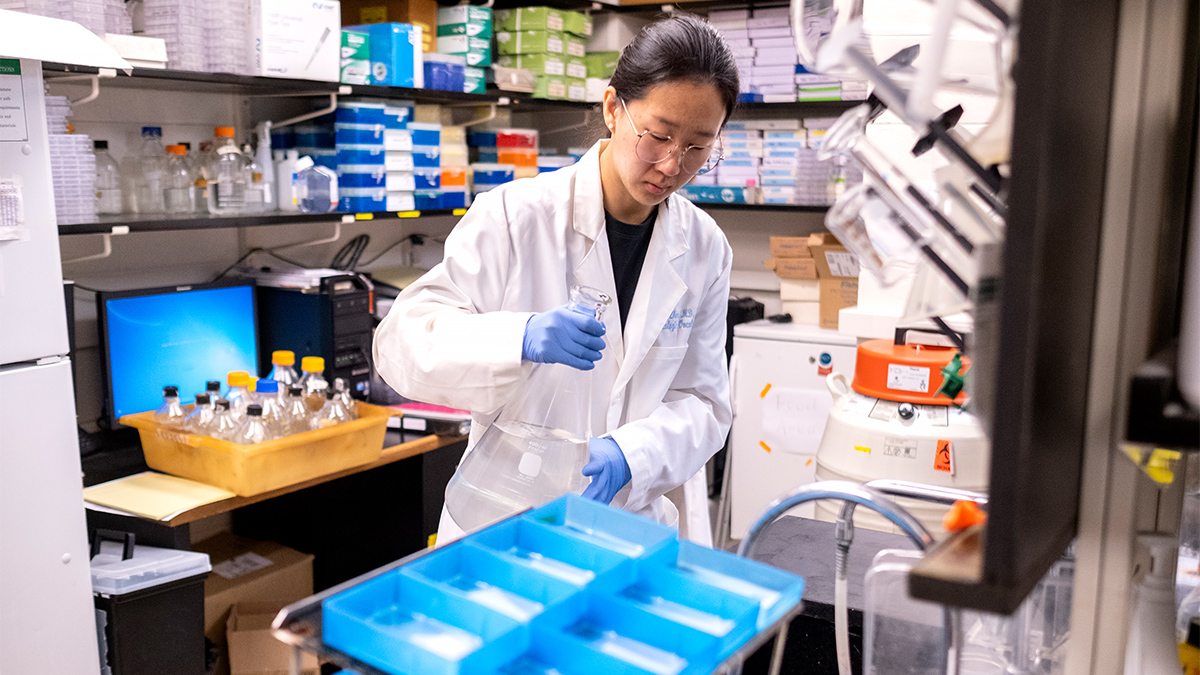

Shuning Chen in the Bae-Jump lab. (Jon Gardiner/UNC-Chapel Hill)

Treating the whole patient

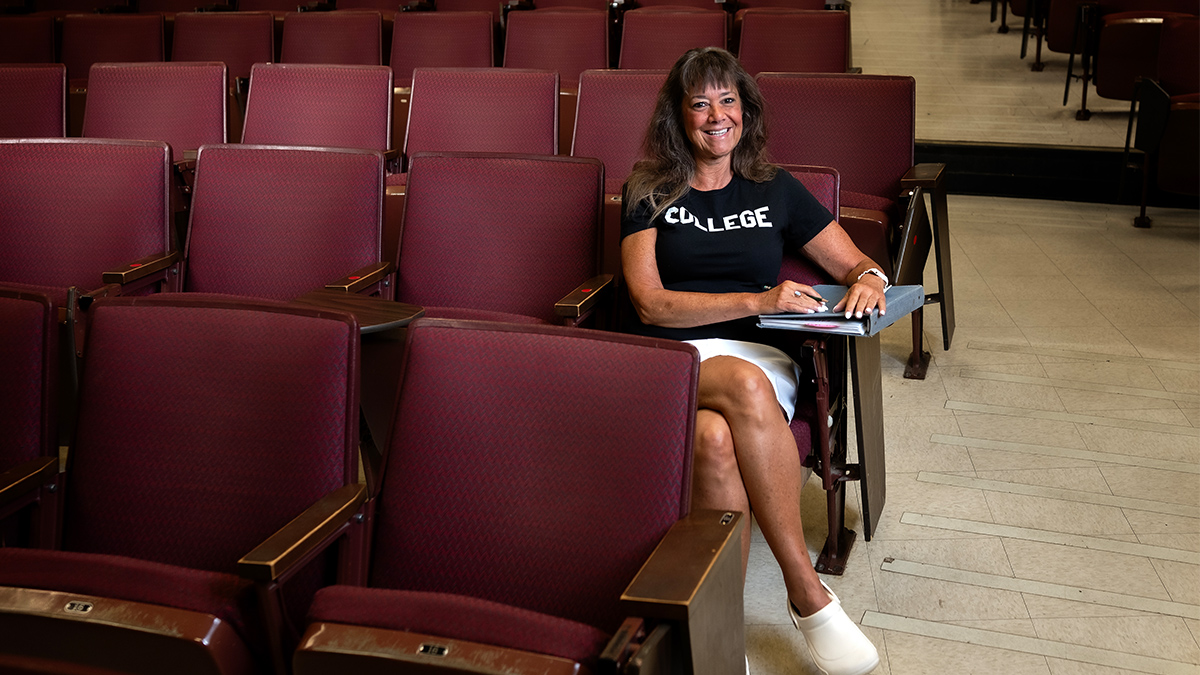

Abbie Smith-Ryan, a professor in the College of Arts and Sciences’ nutrition and exercise and sport science departments, recently wrapped up the first study of pre-surgery high-intensity interval training in endometrial cancer patients. The investigators initially met with study participants the day they were diagnosed. “The women were so excited to have something that they could do to give them a little bit of control over next steps,” she said.

She and her colleagues are still processing metabolomic data, so it’s too early to draw conclusions. But anecdotally, Smith-Ryan said she was excited by what she saw. “We saw them six weeks post-op in the lab, and it was just incredible how much better they felt.” The reaction gave her and Bae-Jump a new idea: to develop an exercise program to send home with patients following surgery.

“You can’t look at a disease through just one lens. From my perspective, exercise is medicine.” Researchers at Carolina get that, she said.

There’s a reason we call them moonshots, these ambitious scientific endeavors meant to solve humanity’s biggest challenges. They’re longshots, like the eponymous effort in 1969 by the Apollo 11 team to reach the moon. To succeed, they demand the collaboration of many people with different ideas and areas of expertise, all working together, their sights set on the same goal, whether that’s skyward or toward a cancer-free future.

In this occasional series about Carolina Next: Innovations for Public Good, The Well looks at how staff, faculty and students are turning the words of the strategic plan into reality.