Musicologist makes case for national hymn

Carolina music professor Naomi André wants Americans to know more about the song “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

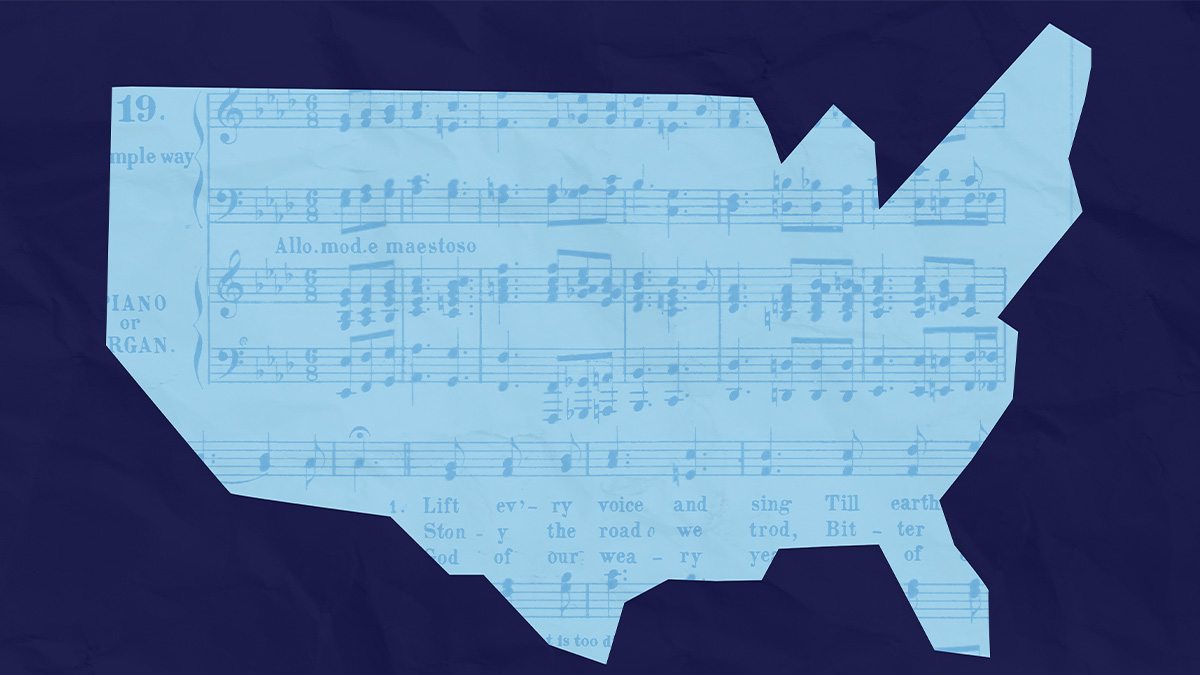

“Lift Every Voice and Sing” would become America’s first national hymn if Carolina music professor Naomi André’s say on the matter counts.

First performed in 1900 by a choir of 500 Florida school children to celebrate the birthday of Abraham Lincoln, who issued the Emancipation Proclamation, the song became known as the Black national anthem. In 2021, U.S. Rep. Jim Clyburn sponsored HR 301, a bill to make “Lift Every Voice and Sing” the national hymn and invited André, a musicologist, to testify at a hearing. André, whose work includes researching and teaching on Black opera, is the David G. Frey Distinguished Professor in the College of Arts and Sciences’ music department.

“My graduate training in musicology included a lot about medieval liturgy and answering questions like ‘What are hymns? What are motets? What are song forms?’ I love to think about such things as they can be applied to the present,” André said.

Naomi André

At the hearing, André described the song’s origins. She said that thinking of the song as a hymn “makes sense because a hymn is a song of praise that’s multidenominational. There are Catholic, Jewish, Byzantine hymns. It’s one of the most inclusive song forms of praise and adulation.”

The lyrics of the song come from a poem by James Weldon Johnson, principal of the first school for Black students in Florida, the Stanton School in Jacksonville. His brother, J. Rosamond Johnson, composed the music for the lyrics. The children who first performed the song were Stanton School students. James Weldon Johnson became the NAACP’s first executive secretary in 1920.

Although the song began in the Black community and became important to the Civil Rights Movement, André sees a broader reach. “There is nothing in the three stanzas that exclusively refers to African Americans. The Black experience is embodied while also referencing the triumphs, struggles and strength that all humans encounter. The text refers to hard work, aspiration, motivation and moving towards victory.”

The song speaks to struggles throughout America’s history, André said, from the American Revolution to chattel slavery, Jim Crow, economic class wars and segregated public education. “Our history continually moves toward democracy. Though we haven’t quite gotten there in all accounts, this song illuminates how the vision persists.”

André points to the song’s rise in mainstream culture, finding two YouTube videos particularly heartwarming. One features a multiracial group of school children at P.S. 316 Stroud Elementary School in Brooklyn, New York. Another shows a diverse U.S. Navy band singing and playing instruments.

The song gained national exposure in 2020, when the National Football League had the song played before every team’s opening game as part of its announced efforts to combat racial injustice. “Some might think that’s an empty gesture, but music has meaning and power,” André said.

Though the bill stalled in Congress, André hopes that it can be resurrected and that the song will become a national hymn. “The song is special; it has a great history and it means a lot to many people already. Moreover, it doesn’t have to be the only national hymn. There may be songs with a lot of meaning in Latinx or Native American communities, for example.”

“It’s America’s music,” she said. “If it were only sung by Black folks, then it would be limiting. This is music that’s not meant to divide people. In fact, it’s just the opposite: It’s about bringing people together.”