Re-examining Old East

Old East, which has changed along with the University, is the setting for an alternative story about Carolina’s foundation.

We think that we know the story of Old East’s beginnings.

But lesser-known stories are, perhaps, more important to understanding the University’s history.

One such story is about an enslaved man named Dave whose strength may have physically and metaphorically set the University’s foundation. The story is but one about the enslaved children, women and men at the center of the economic prosperity of the University, its faculty and its students.

It’s a different story than normally told about Oct. 12, 1793.

The cornerstone ceremony

A block of sandstone hangs from a sturdy-timbered tripod, ready to be lowered to anchor the foundation of what will rise as Carolina’s first building, now known as Old East.

The block sways slightly, its hoist rope twisting and crackling.

Gathered around the southeast corner of the building’s clay footprint are University trustees, state lawmakers, members of the Masonic Order, Revolutionary War heroes and others who were crucial to forming Carolina as the nation’s first public university.

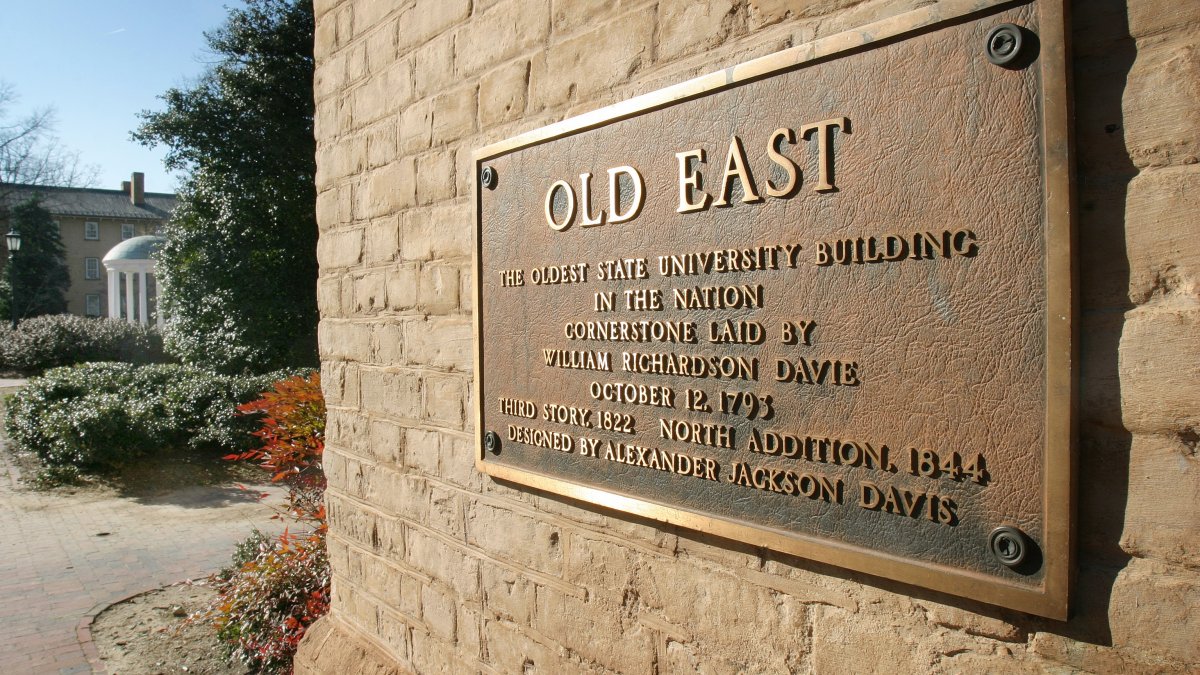

William R. Davie, the University’s founder and North Carolina’s Grand Master Mason, walks forward to place into the cornerstone’s carved slot a brass plaque with engraving marking the event in “New Hope Chapel Hill … [i]n the year of Masonry 5793 and in the 18th year of American Independence.” Davie prepares to pour Masonic ceremonial emblems ─ wine, olive oil and corn ─ on the cornerstone before it is lowered onto the packed soil.

Suddenly, the rope snaps and the cornerstone thuds to the ground, startling Davie and the crowd.

Matthew McCauley, who donated 250 acres of the University’s original land, quickly steps in, directing his 300-pound enslaved body servant Dave to pick up the cornerstone. Dave wraps his arms around the stone, lifts and sets it in place.

Thus, the University’s physical foundation begins, at least as told through McCauley family lore by descendant Kemp Battle Nye in a 1990 article in the UNC General Alumni Association’s University Alumni Report.

Correcting the narrative

Although no record of this story has been found, any fictional license is offset by the reality that McCauley and many of the white men present that day owned slaves who built the University’s pre-Civil War buildings. The enslaved endured cruel conditions while serving faculty and students, said Jim Leloudis, a professor of history in Carolina’s College of Arts & Sciences. Census records, newspapers and correspondence of that time and genealogical research confirm that reality.

It is not until the 1820s that names of enslaved people who built and worked on University buildings appear in University records. The names and related history are coming to light, thanks to the work of librarian University Archivist Nick Graham and staff in University Archives and students in a UNC history course who created a website to record those names. That work is aiding the University’s Commission on History, Race and a Way Forward as it focuses on archives, history, research and curation; curriculum development and teaching; and engagement, ethics and reckoning.

“This is one part of what the commission is talking about,” said Leloudis. “The commission is about correcting the narrative of the University. We’re compiling an ongoing list of enslaved people who were connected to the University in one way or another, initially looking at people who were involved in the construction of the campus. We have a lot of names, and certainly don’t have all the names, but there’s a chance of correcting the narrative and recovering parts of the University’s history.

“There’s something really powerful in just simply speaking those names. People who are attentive to that will walk across the campus and see it in a very different light, if we can find even one of the names related to Old East.”

Oral history, including family lore, has served humankind for centuries and is valuable to anthropologists and historians, not to mention our own families. So, with one story about the building’s beginnings, here’s a look at some of Old East’s history and its enduring appeal.

Historical importance

First called “East Building,” Old East was designated a National Historic Landmark by the National Park Service in 1965. The structure’s importance shows in the University’s increasingly thorough efforts to renovate and revitalize the building over two centuries.

Leloudis said that Old East is perhaps unique among American university buildings in that it has always served as a residence for students.

“It’s actually quite remarkable,” he said. “Talk about a story of survival, that it wasn’t used for various purposes like a lot of campus buildings and it’s had a singular purpose over the years.”

Old East’s original plans called for three stories. Instead, the trustees hired James Patterson of Chatham County to build a two-story brick building just over 96-feet long and 40-feet wide for about $5,000, according to Archibald Henderson’s “The Campus of the First State University.” That history states that the building’s original design “indicates a preoccupation with oriental ideas, in consonance with Moslem mores.” The front was to face East in keeping with “crying the Muezzin (call to prayer)” and “fronting toward the rising sun.”

“With the construction of what we call South Building in 1814, campus was reoriented to a north-south classic Palladium layout,” Leloudis said.

In 1804, University trustees ordered extensive work done to Old East that included new outside doors and repairing window sashes. In 1823, contractors and slaves began work on a third floor, dismantling chimneys to make room.

The thousands of bricks needed for the addition were likely made and fired by enslaved masons in clay pits about one-half mile away in Battle Park, Leloudis said.

“Apparently, clays in this part of the state are similar chemically, so it can be hard to get a fingerprint,” Leloudis said. “It would be interesting to try to verify that. There are some depressions in the woods where they probably were digging the clay.”

Some of what may be bricks from the 1793 chimneys were among the things Leloudis found when he crawled under Old East’s floors in spring 2020. His excursion gave the historian more information to add to what he and his students gathered on the construction of Old East and other University buildings prior to the end of the Civil War.

In 1848 architect A.J. Davis directed renovations that included a lime wash of Old East’s plain exterior and a three-story addition on the building’s north side. The addition dressed up the building with recessed brick panels defined by pillars jutting from the wall and an eight-window panel reaching from the first-floor door to the third floor that exists today.

Work in 1923 replaced the old timber framework with a concrete slab for fireproofing. Work during the University’s Bicentennial period of 1992-1993 renovated most of the interior and restored the exterior to its 1848 appearance, complete with a custom-mixed lime wash.

With the modern building’s dimensions at 125 feet long and 40 feet wide, it was dressed up in 2009 with new copper roofing, gutters and flashing, restored exterior brick walls, removal of existing paint and addition of new lime paint and repainted wooden features.

The building that former University President Kemp Plummer Battle described in an 1883 speech as “no ephemeral structure” clearly has been made sturdier and more attractive over the decades.

Symbol of student life

If the Old Well is the visual symbol of the University, then Old East symbolizes student life.

Old East’s first student resident, Hinton James, arrived in February 1795. He lived there for two weeks until other young men begin arriving. Room rent was five dollars a year, but students had to provide their own beds, wood and candles for their chambers.

Life in Old East during the first few decades exemplified many consistent themes of student life — food (possum dinners, anyone?), friendship, studying, music, questioning authority and all sorts of escapades. According to entries from “Two Hundred Years of Student Life at Chapel Hill: Selected Letters and Diaries” published in 1993, John and Ebenezer Pettigrew arrived in 1795 to find students jockeying for Old East’s best rooms. In 1841, James Laurence Dusenbury writes of requiring a “Fresh” (first-year) student to fiddle so his group had a “real scamper down,” danced, procured a bottle of wine and “pledged each other in flowing glasses” in a night of “songs & social converse.”

Until the Civil War’s end, enslaved people attended to these sons of privilege from across North Carolina and out of state. Enslaved males rose early from where they slept off-campus to set fires and prepare students’ belongings for the day. Women toiled doing laundry or in nearby boarding houses.

In the 1840s, the University forbade students from bringing slaves from home. Carolina faculty and townspeople sold the services of enslaved people to the University and students for two dollars per term (about $56 today), according to ledgers from the 1830s.

“David Lowry Swain, former state governor and University president (1835-1868) had 40 people living in four slave houses behind the President’s House who could be hired out,” Leloudis said.

Despite falling into disrepair at times and escaping serious damage from small fires in student rooms during the 1800s, Old East gained popularity as a residence. Old East remained a male bastion until, in fall 2000, women moved in after members of student government and the Residence Hall Association lobbied University administrators.

A place in Carolina’s conscious

In Carolina’s collective conscious, Old East holds a special place because of its central location on an idyllic campus and its pivotal role in history. Just as the University has changed into a place offering accessible education to people from all walks of life, Old East has changed.

Its residents had front seats to the maturation of public higher education, the effects of a civil war, to times of poverty and prosperity, to preparations for world wars, to protests, sadness and celebration. All while maturing in a place they called their Carolina home.

And, Old East stands as a reminder of the enslaved men and women upon whose bodies and labor the University’s foundation rests.

Visit the TheWell.unc.edu for more photos of Old East through the years