Sayre-McCord makes the abstract accessible … and fun

The Thomas Jefferson Award winner’s “Geoffervescence” is “a tremendous asset to philosophy as an academic field.”

In their end-of-course comments, Geoffrey Sayre-McCord’s students describe him as “amazing,” “engaging,” “academically stimulating,” “respectful” and “brilliant” — as well as “a little goofy, as philosophy professors should be.”

They make it clear that it’s not only the content of an introductory class like “Virtue, Value and Happiness,” with its readings of Plato, Aristotle, Kant and Mills, that has helped them explore the nature of value. It’s also the enthusiastic way he teaches — moving through the classroom, engaging individual students, sharing personal stories — that provides them a living example of a man happy in his work and in his life.

“He finds a way to make dusty philosophic diatribes come alive and applies them well to the lives we live today,” one student wrote of the Morehead-Cain Alumni Distinguished Professor of Philosophy and the director of the philosophy, politics and economics program in the College of Arts and Sciences.

His introductory class addresses the basic questions of life. “What is it to be a happy person? What’s the connection between getting respect and flourishing?” Sayre-McCord said. “Those are all down-to-earth, real issues that we ignore at our peril when we get caught up in the maelstrom of trying to make more money or get bigger houses.”

Showing philosophy’s relevance to everyday life is a driving force behind the class and the rest of Sayre-McCord’s work at Carolina: his development of PPE program and the founding of the Parr Center for Ethics and the National High School Ethics Bowl.

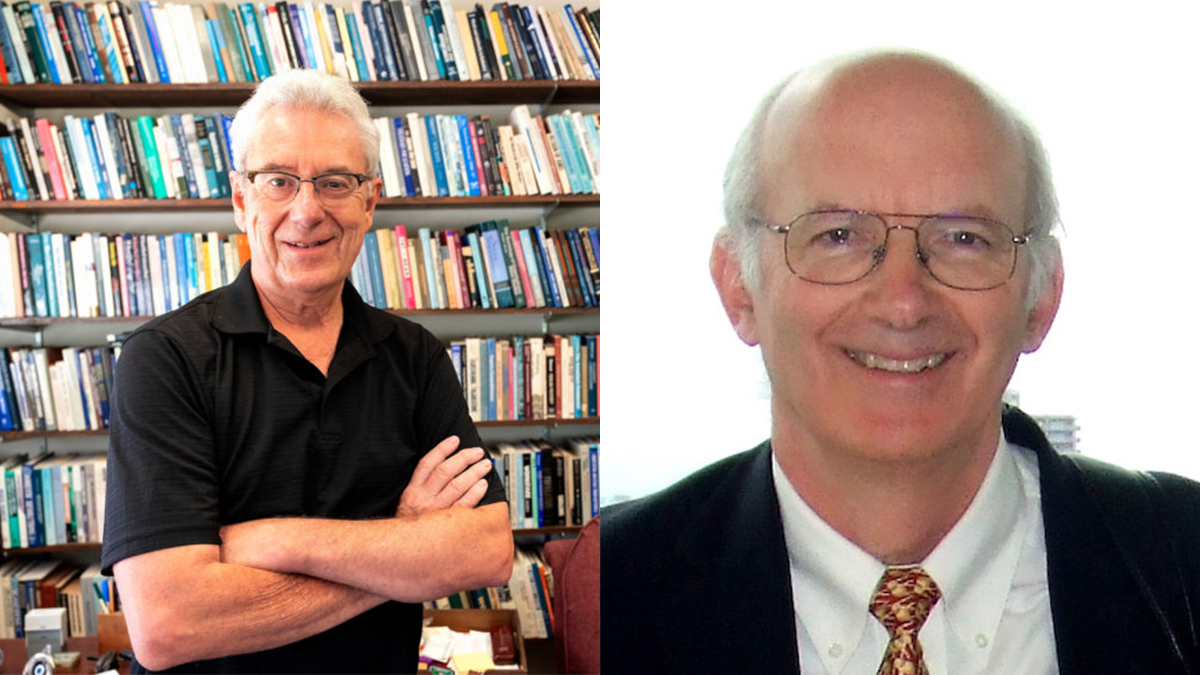

Faculty Council honored Sayre-McCord on Jan. 20 with the 2022-23 Thomas Jefferson Award, presented annually to the faculty member who best exemplifies Jefferson’s values of democracy, public service and the pursuit of knowledge. In 2022, Sayre-McCord also received the UNC Board of Governor’s Award for Excellence in Teaching, the most prestigious teaching award in the UNC System, given each year to a single instructor at each constituent institution.

Marc Lange reads the citation for the presentation of the 2022-23 Thomas Jefferson award as award recipient, Geoffrey Sayre-McCord, and Chancellor Kevin M. Guskiewicz look on. In his nomination of Sayre-McCord, the Theda Perdue Distinguished Professor of philosophy quoted from students’ reviews and praised Sayre-McCord’s “Geoffervescence” as “a tremendous asset to philosophy as an academic field.” (Jon Gardiner/UNC-Chapel Hill)

Pursuit of happiness

Another link between the Jefferson Award winner and the author of the Declaration of Independence is their focus on happiness. Jefferson was the man, after all, who famously transformed John Locke’s list of natural rights from “life, liberty and property” to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

That pursuit led Sayre-McCord to college and philosophy. He didn’t like high school, but Oberlin College was “wonderful, stimulating and interesting,” he said. He took a philosophy class his first semester and fell in love with the subject and with one of his classmates, Harriet Sayre, whose nickname is “Happy.”

“I chased philosophy and her,” he said. The Sayre-McCords were married in 1980 and have two children, two daughters-in-law and two grandchildren.

Sayre-McCord’s attraction to philosophy was, in hindsight, inevitable. His mother, Joan McCord, a professor and criminologist, originally pursued a doctorate in philosophy, first at Harvard, then at Stanford. She eventually switched to sociology because it offered her better job prospects. “Philosophical thinking and discussion were a daily part of my life long before I had any idea what philosophy was,” he said.

Applying philosophy to life

Sayre-McCord’s focus in recent years has been the interdisciplinary PPE program, established in 2005. With more than 400 minors this year, the fast-growing program is the largest of its kind in the country. The PPE minor requires five courses: one course each in philosophy, politics and economics, with a PPE Gateway course to begin and a PPE Capstone to end. Just what the next steps are for the PPE program is under discussion. Possibilities include a PPE major or a four-plus-one degree, in which a student could convert a minor in PPE into a master’s degree with one additional year of study.

The driving idea behind the interdisciplinary program is that the social and political institutions that shape our lives and opportunities can best be understood by bringing together the tools, concepts and discoveries of the three disciplines. “Each discipline shines a bright spotlight on social life, revealing details that we would never see without the benefit of that discipline. Yet each also casts a long shadow,” he observed. “The PPE program seeks to minimize the shadows by bringing the three together.”

Geoffrey Sayre-McCord (Jon Gardiner/UNC-Chapel Hill)

Ethics in competition and class

A commitment to philosophy’s relevance to everyday life naturally led to Sayre-McCord’s involvement with the Parr Center for Ethics (which he helped establish in 2004). Among its many lectures, programs and events focusing upon ethical questions in the arts, sciences and professions is the National High School Ethics Bowl.

The Ethics Bowl reaches approximately 4,000 high school students each year, offering them the kind of challenging, thought-provoking learning Sayre-McCord felt he didn’t get in his high school. In the competition, the teams discuss realistic scenarios that present ethical dilemmas. The Ethics Bowl competitors don’t debate in the traditional sense. Rather, teams must answer a difficult question prompted by the case and are scored on the quality of their contribution to a discussion about the question.

In his classes, Sayre-McCord regularly asks students to interview an elder about a difficult moral decision they faced as a way to help them appreciate how moral theory can and does apply to people they know. One example came from a student whose minister faced the dilemma of whether he should connect a parishioner with glaucoma to a parishioner who sold marijuana. He would be facilitating an illegal activity. But he would also be helping someone reduce her suffering.

“As relayed by the student, the minister was facing what was for him, a poignant, complex moral decision. To share that with the student was a genuine gift. It offered an excellent example of the kind of choices people can find themselves facing,” Sayre-McCord said. “That was really beautiful.”