She trains Black doulas to close the maternal mortality gap

Black women die from childbirth at higher rates than white women. The School of Medicine’s Venus Standard hopes to change that.

Content warning: This article mentions sexual violence.

Black women in the United States are nearly three times more likely to die in childbirth than white women, according to the most recent report on U.S. maternal mortality rates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s true across income and education levels. In fact, the maternal mortality rate for Black women with at least a college degree was five times higher than similarly educated white women.

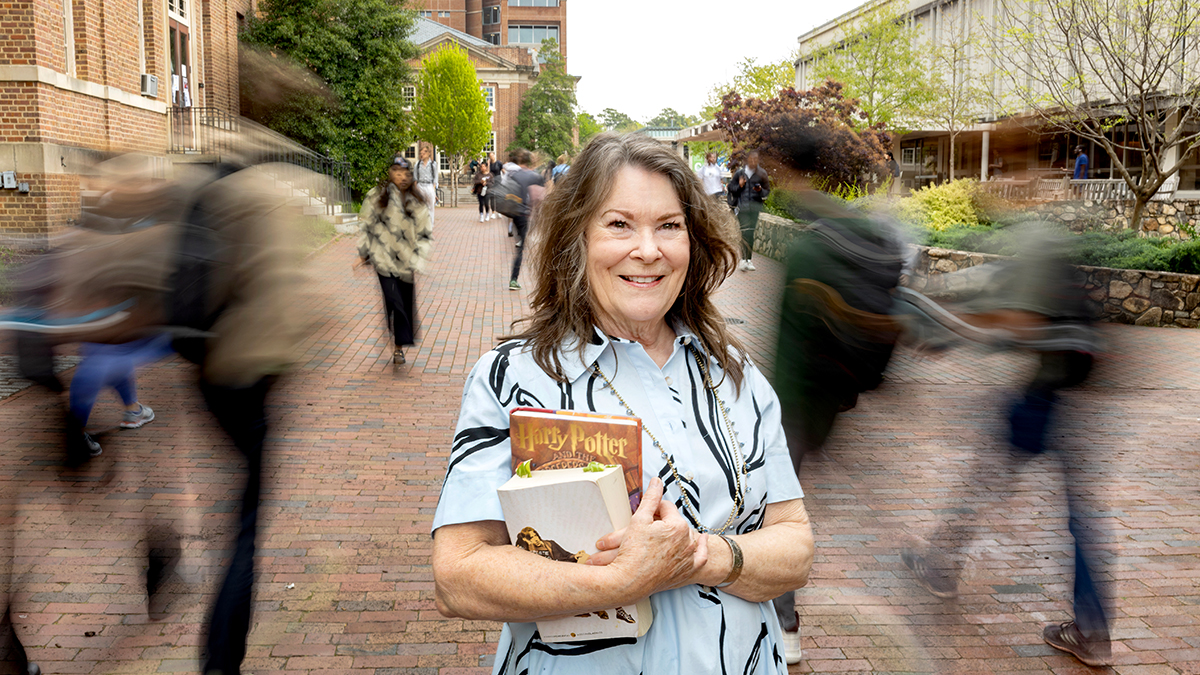

Venus Standard, among other Carolina experts, is addressing the disparity.

Venus Standard

An assistant professor in the UNC School of Medicine’s family medicine department, Standard and two others created the Lived Experience Accessible Doula, or LEADoula, program to improve Black maternal and birth outcomes by training Black doulas to provide support and education to Black women.

In 2021, Standard and her co-principal investigators — Duke University Assistant Professor Jacquelyn McMillian-Bohler and Vanderbilt University Associate Professor Stephanie DeVane-Johnson — received funding for a one-year pilot program through Carolina’s C. Felix Harvey Award. With additional funding from The Duke Endowment, the trio hopes to expand the program into other North Carolina counties and even other states.

Standard, who is an advanced practice registered nurse, certified nurse-midwife and certified doula, spoke about the program, its goals and the importance of the work.

Describe your work with LEADoula.

We’re training women to be doulas who can help support families, be their educators, teach them things they may not have known about their bodies and their rights as pregnant people. To help them not only by supporting them in the laboring process — because that’s the crux of their job — but by educating them and being their advocates. Not to be their mouthpieces, but their advocates — to let them have a voice.

In the first year, we trained 20 doulas. With three years of additional funding from The Duke Endowment, we have trained 65 doulas so far, with a goal of training 140 total over the four years.

Most of the challenge of the numbers is historical; it wasn’t perceived as a problem that Black women were dying three or four times more than anybody else. The numbers are not new — the CDC has been tracking this for decades. Because people that we see on television, social media and media outlets are bringing it to the forefront, it’s now being visited.

What is a doula and how does their role differ from that of an OB-GYN or midwife?

An OB-GYN, a certified nurse-midwife, a certified midwife — we are all medical professionals. We are trained for years and years to do what we do. We’re trained to do medical procedures, to write prescriptions, to do assessments and care, to diagnose.

Doulas do not do that. A doula’s function is to support the person in their desire to have the birth that they want. It’s not about what the doula wants or what the doula’s history is; it’s about trying to give the person giving birth the best possible experience for what they want.

Jacquelyn McMillian-Bohler

Although we are serving the same person, we are serving in different capacities, so they don’t necessarily overlap.

A doula gives 24/7 access and uninterrupted labor support. Although midwives and OBs have compassion, they have so many other things to do and people to see that they can’t just be in that one room at that time. They can’t always answer their phones at 3 a.m. That’s the doula’s job.

Why is it important to train Black doulas?

Studies show that doulas decrease negative birth outcomes and are amazing at increasing patient satisfaction rates. Historically, Black people do not trust the white medical community. They are giving their trust to the Black doulas, the doulas who look like them. We serve Black families, so they often trust their doulas to have their best interest at heart — a lot more than they trust their providers.

The families tell doulas things, and the doulas are instructed to call me if something doesn’t seem right or if they’re concerned about a patient. I had one patient who was pregnant by rape, and that was nowhere on her medical chart, but she felt comfortable and safe enough to tell a doula.

Stephanie DeVane-Johnson

The doula is there to be the gatekeeper, to try to calm patients’ fears while educating them, to understand what their rights are and how they should be cared for. A patient’s opinions and thoughts should be respected. A doula is not there to make medical decisions, but she’s there for her patients. They know that their bodies — and thoughts, concerns and wishes — should be valued. Historically that has not happened.

It’s all about listening and being respectful to the birthing person and understanding that it’s not about the caregiver; it’s about the patient. We put them first and foremost and put our judgments or prejudice aside.

What inspired you to focus your work on improving health outcomes for Black women?

The disparities are so drastic. You notice as you’re going through your training, learning your work and entering the field that things are so different, that white people get offered things that Black people don’t get offered in the same exact situation.

One of the reasons our team does what we do is to bring that gap between the “haves” and the “have-nots” closer together. When you take away age, money or education, it doesn’t matter. The only common denominator is their race. We’ve come a long way so far with other things, but this stayed the same.