Paul Hardin, Carolina’s seventh and ‘bicentennial chancellor,’ passes away at age 86

Paul Hardin III, Carolina's seventh chancellor, challenged the University to 'think big and to dream.'

Chancellor Emeritus Paul Hardin III, who led the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill during its Bicentennial Observance, died at his Chapel Hill home Saturday (July 1) after a courageous battle with ALS. He was 86.

“Chancellor Paul Hardin was a visionary leader who is remembered in North Carolina and across our nation for his dedication to promoting the life-changing impact and benefits of higher education,” Chancellor Carol L. Folt said. “In his bicentennial address, alumnus Charles Kuralt spoke of how Carolina was meant to be ‘the University of the people.’ Paul seized upon Carolina’s 200th birthday as an opportunity to light the way to a better future and open Carolina’s doors for all North Carolinians. Paul was warm and gracious and remained very involved with Carolina after his retirement. He will be greatly missed.”

Born in Charlotte on June 11, 1931, Hardin was the son of Methodist minister and bishop Paul Hardin Jr. and Dorothy Reel Hardin. He grew up in numerous North Carolina towns as his father moved from church to church.

He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Duke University in 1952 and then first in his class in its law school. He served as editor-in-chief of the Duke Law Journal. After serving in the U.S. Army’s counterintelligence unit, he worked as a lawyer. He taught at Duke Law School for 10 years, eventually becoming a full professor before embarking on a career as a university president.

He served as president at Wofford College (1968-1972); Southern Methodist University (1972-1974); and Drew University (1974-1988) before becoming Carolina’s seventh chancellor on July 1, 1988.

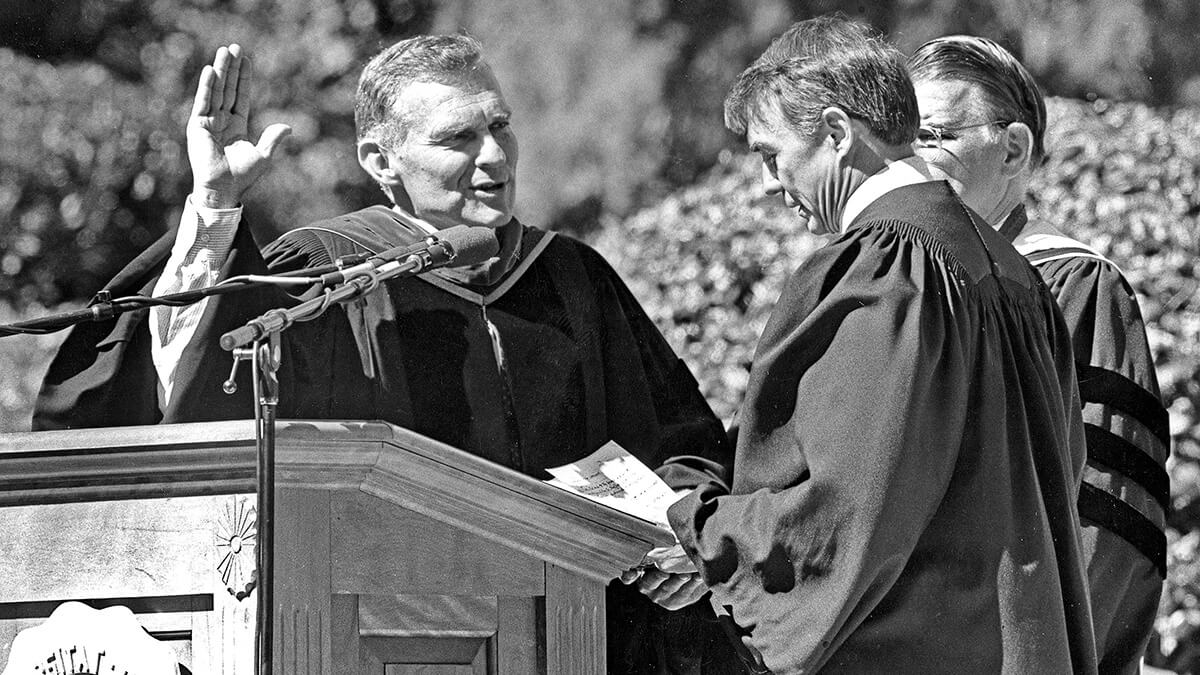

At his installation, Hardin told the attendees that “the future belongs to those institutions and persons who command it, not to those who wait passively for it to happen.” By the time he stepped down in 1995, “The Bicentennial Chancellor” had presided over some of the most important events in the life of the University and left Carolina poised for its third century.

Hardin described the Bicentennial era as a magnificent opportunity that would never come again. “Dare to think big and to dream,” he said, and so they did.

The Bicentennial Observance touched all 100 counties and culminated with the celebration in Kenan Stadium on Oct. 13, 1993, when Hardin conferred an honorary degree on President Bill Clinton. The yearlong celebration proved to be a catalyst for the five-year Bicentennial Campaign for Carolina that brought in $440 million in private gifts – $120 million above the goal.

A civil rights advocate who pushed for the integration of Durham’s public facilities in the 1960s, Hardin helped double minority representation on Carolina’s faculty. He also played a key role in the naming of the undergraduate admissions office in honor of pioneering black faculty members Blyden and Roberta Jackson.

Hardin established the Employee Forum, which gave non-academic University employees a greater voice. He was a staunch advocate for UNC-Chapel Hill and helped campaign successfully for greater fiscal and management flexibility for the state’s public universities.

He signed the agreement to build the Southern Observatory for Astrophysical Research with Brazil and the National Optical Astronomy Observatories. He also steered the University community through a controversy that ultimately led to the successful completion of the Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History. After stepping down as chancellor in 1995, Hardin served on the School of Law faculty.

Hardin’s awards included the 1995 North Carolina Public Service Award, a General Alumni Association Distinguished Service Medal in 2003 and a 2004 William Richardson Davie Award from the UNC trustees, the highest honor bestowed by the board, for service to the University or society. He also received many honorary degrees.

Hardin served on the Carolina Performing Arts Society National Advisory Board and attended many performances in Memorial Hall. He was an active lay leader in the United Methodist Church, held numerous community leadership roles and served on several corporate boards. He also was a national leader in higher education; his accomplishments included service as a charter member of the NCAA Presidents’ Commission.

In March 2007, Hardin and his wife, Barbara, joined with then-Chancellor James Moeser and Chancellor Emeritus William Aycock and former Interim Chancellor Bill McCoy for the dedication of Hardin Hall, a newly built residence hall on south campus named in his honor.

Also on hand was Dick Richardson, a retired provost and political science professor who chaired the Bicentennial Observance while Hardin was chancellor.

Richardson said the essential quality of leadership Hardin possessed was his great comfort being himself. There is no veneer to him. No pretense, no façade of personality to hide the real person, Richardson said.

“If you scratch deeply beneath the surface of Paul Hardin, you will find exactly what you find on the surface, for this man is solid oak from top to bottom,” Richardson said.

Hardin is survived by his wife of 63 years, Barbara Russell Hardin, three children, nine grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

A memorial service will be held at 3 p.m. Saturday, July 8, at University United Methodist Church in Chapel Hill. In lieu of flowers, the family suggests gifts may be made to The Robert and Martha Gillikin Library Fund in honor of Paul and Barbara Hardin at the UNC-Chapel Hill Libraries, the Duke University ALS Clinic, the Paul Hardin Scholarship Fund at the Duke Law School or the Hardin-Russell Endowment Fund at Lake Junaluska Assembly.

The University plans to ring the South Building bell seven times on the day of Hardin’s memorial service, to honor his role in UNC history as the seventh chancellor. The ringing of the bell is used to mark only the most significant university occasions.

You may also wish to read a story from the General Alumni Association and the obituary in the News and Observer. Watch a replay of Hardin’s memorial service here.