The men behind the names

Many campus buildings honor white supremacists, but four top the list for renaming, according to the University Commission on History, Race and a Way Forward.

While the racist and white supremacist namesakes of dozens of areas on Carolina’s campus have been discussed for decades, the debate has gained momentum in recent years as other universities and communities have removed statues and renamed buildings.

On July 10 — just weeks after the University’s Board of Trustees overturned a moratoriumon renaming buildings — the University Commission on History, Race and a Way Forward recommended that the names of four white supremacists with particularly shameful histories be removed from campus.

“This is a first step, but it is a beginning,” said commission Co-Chair James Leloudis, a history professor who presented the evidence about the four men on the list: Charles Brantley Aycock, Julian Shakespeare Carr, Josephus Daniels and Thomas Ruffin Sr.

The biographies of these extremely influential men show that they were not just “men of their times,” Leloudis said. Instead, they used their positions of power to pass laws and fund institutions that established white supremacist rule of the state, while also resorting to violence to maintain that supremacy.

The Commission sent a list of the four buildings, with historical evidence supporting their recommendations, to Chancellor Kevin M. Guskiewicz. During the July 16 University Board of Trustees meeting, Guskiewicz requested that the list be considered in a special meeting by July 31.

Read on to learn more about these men and their legacies. Historical information is from the commission and other resources — a full source list is published at the end.

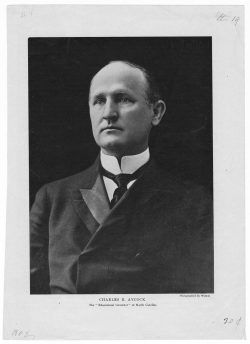

Charles Brantley Aycock (UNC Libraries)

Aycock Residence Hall

- Constructed in 1924 along with Graham and Lewis residence halls

- Has always served as a residence hall, currently all women

- Named in 1928 for Charles Brantley Aycock (1859-1912)

Charles Brantley Aycock was known as the “education governor” of North Carolina (1901-1905), who promoted “universal education” for the state’s children but under a “separate but equal” public school system. Before becoming governor, Aycock spearheaded the Democratic Party’s white supremacy campaign that led to the Wilmington Massacre of 1898, the only coup d’état ever to take place on American soil. In the massacre, a mob of 2,000 white men overthrew the elected government, murdered as many as 300 people, mostly Black, and destroyed dozens of Black businesses. As a governor, Aycock helped pass new laws to disenfranchise Black voters, including voter literacy tests and the infamous “grandfather clause” that meant the tests applied only to Black citizens. Aycock was a prime architect of Jim Crow laws and government in the state.

In his own words, from the speech “Education, The South’s First Need”:

“Let the negro learn once for all that there is unending separation of the races, that the two peoples may develop side by side to the fullest but that they cannot intermingle; let the white man determine that no man shall by act or thought or speech cross this line, and the race problem will be at an end. These things are not said in enmity to the negro but in regard for him. He constitutes one third of the population of my State: he has always been my personal friend; as a lawyer I have often defended him, and as Governor I have frequently protected him. But there flows in my veins the blood of the dominant race; that race that has conquered the earth and seeks out the mysteries of the heights and depths.”

Note: Charles Brantley Aycock should not be confused with his cousin William Brantley Aycock, UNC-Chapel Hill Chancellor (1957-1964) and namesake of Aycock Family Medicine Center.

Name removed: Both East Carolina University and Duke University removed Aycock’s name from residence halls in 2015, and UNC-Greensboro renamed its auditorium in 2016.

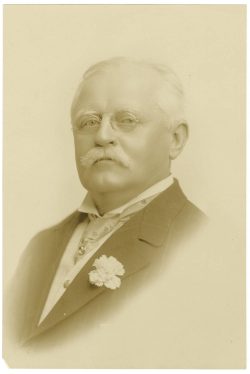

Julian Shakespeare Carr (UNC Libraries)

Carr Building

- Constructed in 1900, the first building on Carolina’s campus fully funded by a single donor during his or her lifetime

- Served as a residence hall through the 1970s; converted to office space in the 1980s; currently the home of faculty governance, student affairs and several other offices

- Named in 1900 for Julian Shakespeare Carr (1845-1924)

Julian Shakespeare Carr was a teenage Confederate soldier who later became one of the area’s most successful businessmen and philanthropists. Carr and a partner developed the popular Bull Durham Tobacco brand and made millions when he sold it to the American Tobacco Company. He also developed businesses in textile manufacturing (Carrboro’s Carr Mill) and electrical power. Carr admitted in 1921 to being a member of the Reconstruction-era Ku Klux Klan, which used vigilante violence to enforce white supremacy across the state. Carr was arrested for breaking up a Black political meeting in 1865 and accused of assaulting a Black woman in 1868, but escaped prosecution by federal authorities. Later, he used his wealth to help his friend Josephus Daniels buy The News & Observer in Raleigh, the mouthpiece of the 1898 white supremacy campaign that led to the Wilmington Massacre. Carr also promoted the widespread placement of monuments to the Confederacy and the “Anglo Saxon race,” including the one at Carolina known as Silent Sam.

In his own words, from a speech at the 1913 dedication of the Confederate Monument at Carolina:

“The present generation, I am persuaded, scarcely takes note of what the Confederate soldier meant to the welfare of the Anglo Saxon race during the four years immediately succeeding the war, when the facts are that their courage and steadfastness saved the very life of the Anglo Saxon race in the South.” He also told the crowd: “One hundred yards from where we stand, less than ninety days perhaps after my return from Appomattox, I horse-whipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds.”

Name removed: Duke University removed his name from one of its buildings in 2018, and Durham Public Schools removed his name from a junior high school in 2017. A movement is underway in Carrboro to rename the town, originally known as Venable but renamed in 1913 at Carr’s request.

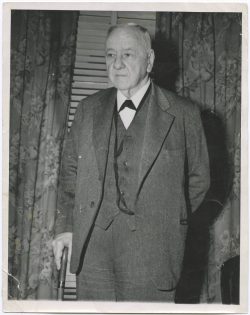

Josephus Daniels (UNC Libraries)

Josephus Daniels Building

- Constructed in 1968

- Served as home of Book Exchange (later UNC Student Stores), Bull’s Head Bookshop and other offices and services

- Named in 1968 for Josephus Daniels (1862-1948)

Josephus Daniels, a longtime member of the UNC-Chapel Hill Board of Trustees, owned and published The News & Observer in Raleigh for decades, which he used — through inflammatory editorials, political cartoons and yellow journalism — to support the Democratic Party’s white supremacy campaign in 1898 that led to the Wilmington Massacre. Later, as U.S. Navy Secretary (1913-1921) under President Woodrow Wilson, he segregated the Navy and brought Jim Crow laws to U.S.-occupied Haiti, whose people had overthrown white colonial rule to establish a free republic in 1804.

In his own words, from a Jan. 28, 1900, editorial in The News & Observer:

“The greatest folly and crime in our national history was the establishment of negro suffrage immediately after the War. Not a single good thing has come of it, but only evil.”

Name and statue removed: The Daniels family removed the Josephus Daniels statue from Raleigh’s Nash Square in June 2020. Later that month, North Carolina State University decided to remove Daniels’ name from one of its buildings.

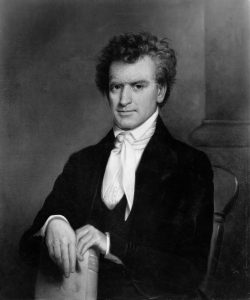

Thomas Ruffin Sr. (UNC Libraries)

Ruffin Residence Hall

- Constructed in 1922, at the same time as nearby Grimes, Mangum and Manly

- Served as men’s residence hall until converted to women’s residence hall in 1976

- Named in 1922 for Thomas Ruffin Sr. (1787-1870) and his son Thomas Ruffin Jr. (1824-1889)

Thomas Ruffin Sr. and Thomas Ruffin Jr. were both lawyers and judges who served on the North Carolina state supreme court. While Ruffin Jr. was a Confederate officer and military judge, the commission focused its attention on the elder Ruffin. A Board of Trustees member, Ruffin Sr. was also one of the largest slaveholders in the state and a partner in a slave-trading business that frequently separated and sold children away from their parents. As chief justice of the state supreme court, he often deviated from case law to rule in favor of the worst abuses of slavery, including not prosecuting a slaveholder for murder.

Statue and portrait removed: Earlier this month, workers removed a statue of Ruffin Sr. from the entrance of the state Court of Appeals building. Orange County officials removed Ruffin’s portrait from the county courthouse in January.

In his own words, from Ruffin Sr.’s ruling in State v. Mann in 1829, which held that slaveholders could not be indicted for injuring those they enslaved:

“The power of the master must be absolute to render the submission of the slave perfect.”

Sources:

“UNC A to Z: What Every Tar Heel Needs to Know about the First State University,” by Nicholas Graham and Cecelia Moore (University of North Carolina Press, 2020)

“Names Across the Landscape,” an exhibit in The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, launched in 2006 as a collaboration between The UNC Center for the Study of the American South, the University History Council and The University Library.

“Names in Brick and Stone: Histories from the University’s Built Landscape,” a website produced by the students in History/American Studies 671: Introduction to Public History