‘The wonder that’s there’

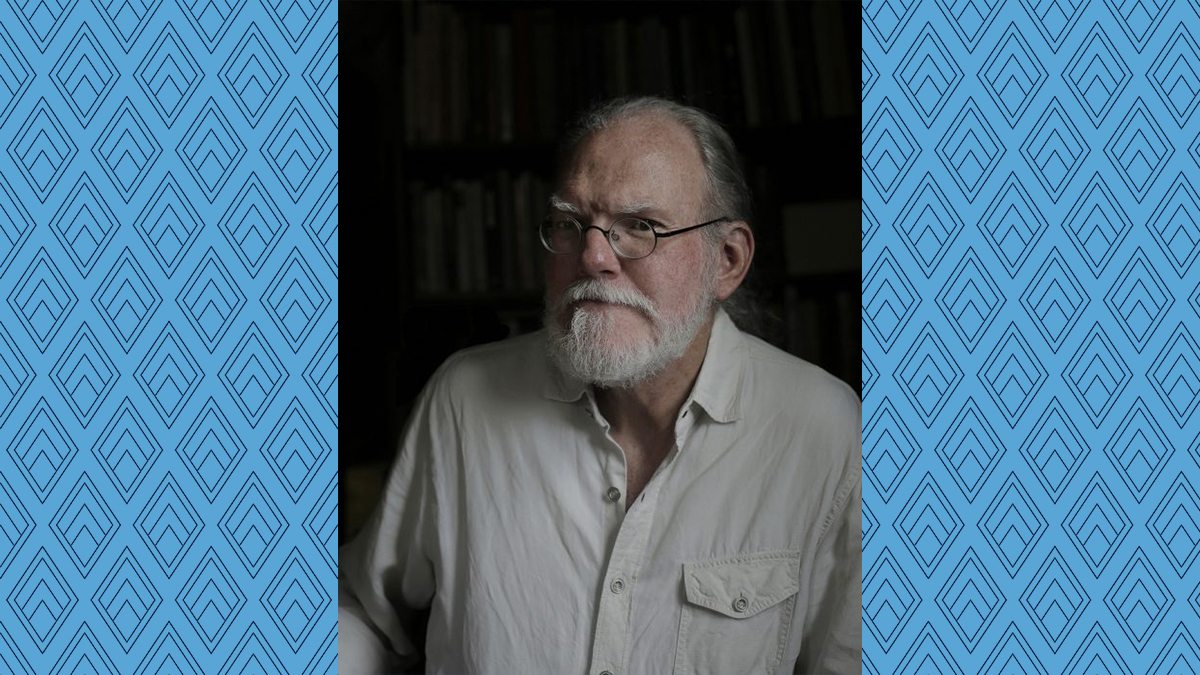

In the Last Lecture for the Class of 2021, associate professor and folklorist Glenn Hinson shared lessons learned in a life of collecting the stories of others.

The faculty member who gave Carolina’s Class of 2021 its Last Lecture told those who joined his April 20 talk via Zoom that when he was their age, he never thought he would give lectures at all.

“I knew when I graduated that I was going to be a folklorist. I also knew that I would never, ever, ever teach at a university, but that I would always be listening,” said Glenn Hinson, associate professor of anthropology and American studies in the College of Arts & Sciences. He found a way to be both a folklorist and an academic at Carolina, where he has been on the faculty since 1989.

The Last Lecture tradition began at Carnegie Mellon in 2007, when professor Randy Pausch gave a special talk after he learned that his pancreatic cancer was terminal.

At Carolina, the Last Lecture is an informal talk given the month before graduation by a speaker selected by the senior class. Hinson, recipient of a 2021 Chapman Family Teaching Award, was the faculty member invited this year to deliver a talk on the premise, “If you knew this was the last lecture you would ever give, what would you share with seniors?”

Speaking from a room with many crafts on display, Hinson told seniors the story behind one of the handcrafted items and the lessons of “gentle elegance” he learned from its creator, Black basket weaver Leon Berry.

He admired Berry’s artistry in peeling thin strips of oak, scraping them down to velvety suppleness and weaving them precisely and evenly into elegant shapes. But when Hinson discovered that “what looked like oversize bullets” were meant to be submerged in muddy creeks to trap fish, he did not understand why Berry took such care in his craftsmanship.

“Why all this work, why all this elegant proportionality, for something that nobody’s ever really going to see? Think about it. The only folks that are going to be spending any time with these baskets are the fish,” Hinson said. “It took me a long time, over many conversations with Mr. Berry, to begin to grasp the answer, an answer that’s all about making wonder.”

African technology

The more Hinson listened to Berry, who was in his 80s at the time, the more he learned about the rich history behind the fish baskets. Berry had learned the craft from his grandfather, a formerly enslaved man whose basket weaving skills had allowed him to avoid harsher field labor on a cotton plantation when he was younger.

“He was the plantation’s basket maker,” Hinson said. And while most of his baskets were employed in the work of the plantation or the pleasure of its white owners, he made the fish baskets only for the benefit of his fellow enslaved people. The traps made it possible for them to supplement their meager meals of cornmeal and salt pork with fresh fish in a way that “didn’t interfere with enslavement’s sunup to sundown labor schedule,” Hinson said.

Instead of sitting on a riverbank with a pole waiting for a fish to bite, they could place bait deep inside the trap — at the end of an inverted cone formed by pliable pieces of wood — and submerge it in a creek.

“The fish go in and they can’t get back out,” Berry told him.

The ingenious design of Berry’s grandfather’s fish traps is strikingly similar to river traps used in West Africa. “These baskets were almost certainly an African technology adapted by enslaved African Americans to the very different natural environment of the American South,” Hinson said.

And this is where the lesson of beauty in the service of practicality became even more profound for Hinson.

“Consider for a moment the conditions of enslavement, a system of perpetual and unrelenting terror, where the guiding white assumption is that the enslaved are fundamentally less than human,” Hinson said. But whenever enslaved people used their creativity and intelligence, “every such act, whether fleeting like the song or sustaining like the basket or the quilt, was an act of both affirmation and defiance.”

‘So many stories’

Hinson describes much of his research as an exploration of the “expressive worlds of African America” and wrote a book in 2000 on African American gospel music called “Fire in My Bones.” Hinson also has been involved in a wide range of public projects that share often overlooked experiences in a broader context, through museum exhibits, presentations and public-school programming.

Since 2015, he has been particularly interested in telling the stories behind African American lynchings. In 2019, his “Southern Legacies: The Descendants Project” class interviewed nine descendants of 1921 Warren County lynching victim Plummer Bullock at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. Just before the pandemic, first-year students in his 2020 seminar “By Persons Unknown: Race and Reckoning in North Carolina” investigated the story of the Norlina 18, a group of Black men in Warren County arrested in January 1921 after defending their community from an advancing white mob.

In the chat following Hinson’s Last Lecture, a student asked him, “What drives that curiosity, passion and purpose?”

“The wonder that’s there,” Hinson said. “The world is filled with so many stories. The world is filled with so many experts. We like to say as ethnographers that people are the experts of their own experience. There’s so much to be learned if we simply listen and engage. It transforms who we can be.”