Brain scans show effects of ‘everywhere chemicals’

Carolina researchers are studying how chemicals widely used in plastic products impact development in children.

Plastics are disrupting our health and day-to-day lives. Certain chemicals called phthalates, sometimes known as “everywhere chemicals,” are used to make plastics more durable and food packaging more flexible. They are found in a wide range of consumer goods, including personal care products, vinyl flooring and shopping bags.

Exposure to phthalates has also been linked to problems in children’s brain development.

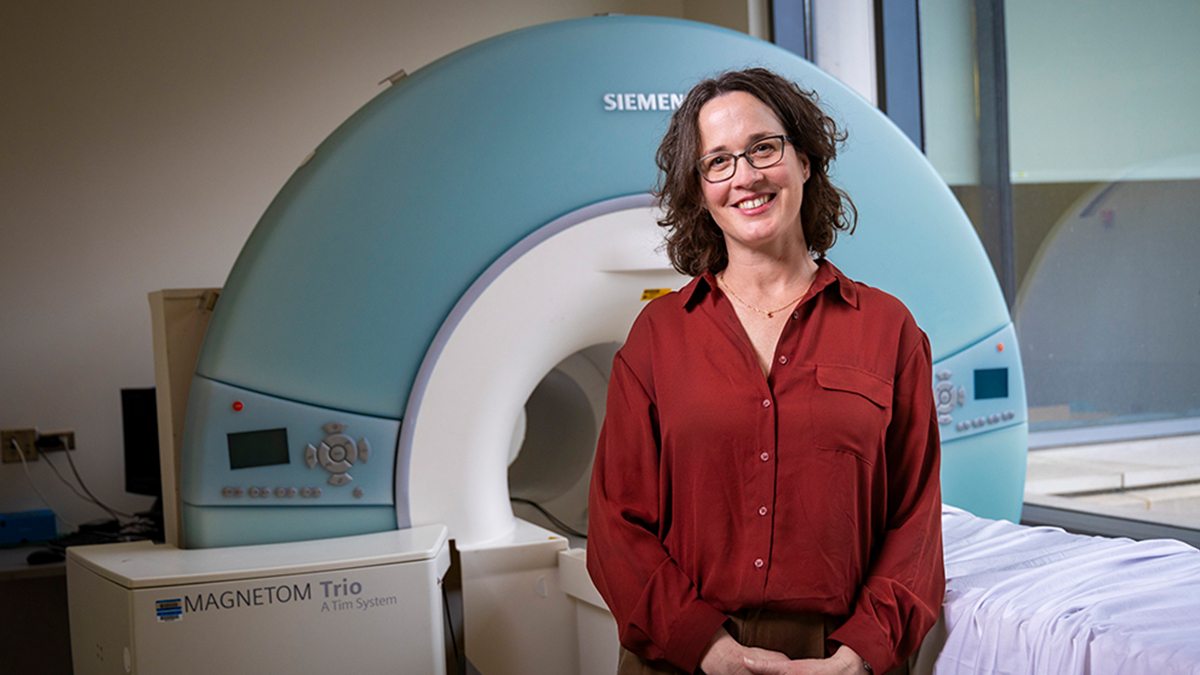

Stephanie Engel, a professor in the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health and director of the UNC Center for Early Life Exposures and Neurotoxicity, has spent the past 20 years studying the effects of phthalates on babies and children. Her research has found an association between exposure in the womb and clinically diagnosed ADHD.

“Phthalates can migrate out of whatever they’re in,” Engel says. “From a container of lotion or your shampoo or cosmetics, it can absorb into your skin. You can ingest it from water bottles. Or it could be in food with plastic wrap around it. All routes lead to phthalate exposure.”

Now she is working with Weili Lin, director of the UNC Biomedical Research Imaging Center and the Dixie Lee Boney Soo Distinguished Professor of Neurological Medicine in the UNC School of Medicine. Engel and Lin are leading a study that uses magnetic resonance imaging to scan children’s brains. They hope to gain a better understanding of how phthalate exposure in early life affects brain growth and development.

Brain pictures

By the 2010s, there was mounting evidence that prenatal exposure to phthalates could be problematic for a child’s brain development, and that young children were being exposed to certain kinds of phthalates more than adults.

Engel was concerned about the impact of high exposure during the first two years of a child’s life because of the massive growth and development that takes place in the brain during this time.

In 2016, she met Lin, who was overseeing the Baby Connectome Project, which focused on characterizing early brain development during the first five years of life. The study used MRIs — a noninvasive imaging technique used to capture detailed images of soft tissue and organs — to map the development of the human brain from birth through early childhood.

When Engel learned of his project, she was eager to partner with Lin.

“By taking a picture of the brain at different points during development, we can see how that child’s brain compares to other children with higher or lower exposure to phthalates,” Engel says. “It’s similar to how we monitor growth curves for height and weight in children.”

Using brain scans, Engel could start to piece together how phthalate exposures in early life might change the structural and functional development of the brain.

“It’s really complicated because what we’re trying to look at is not just the relationship of exposure at one point in time with brain development at a single age, but how exposure over time influences the arc of brain development,” she explains. “And both things are changing — a child’s exposure changes, and their brain changes.”

Engel hopes to illuminate the direct effects of phthalates on children’s brains and is sharing early findings with the broader scientific community.

“I do think a picture is worth a thousand words. And the fact that we have pictures of the brain can be very influential from a policy perspective,” she says. “I want my research to help inform sensible environmental policy that can protect the development of children’s brains.”

Read more about Engel’s and Lin’s study of phthalate’s effects on children’s brains.