Bullying researcher makes schools safer

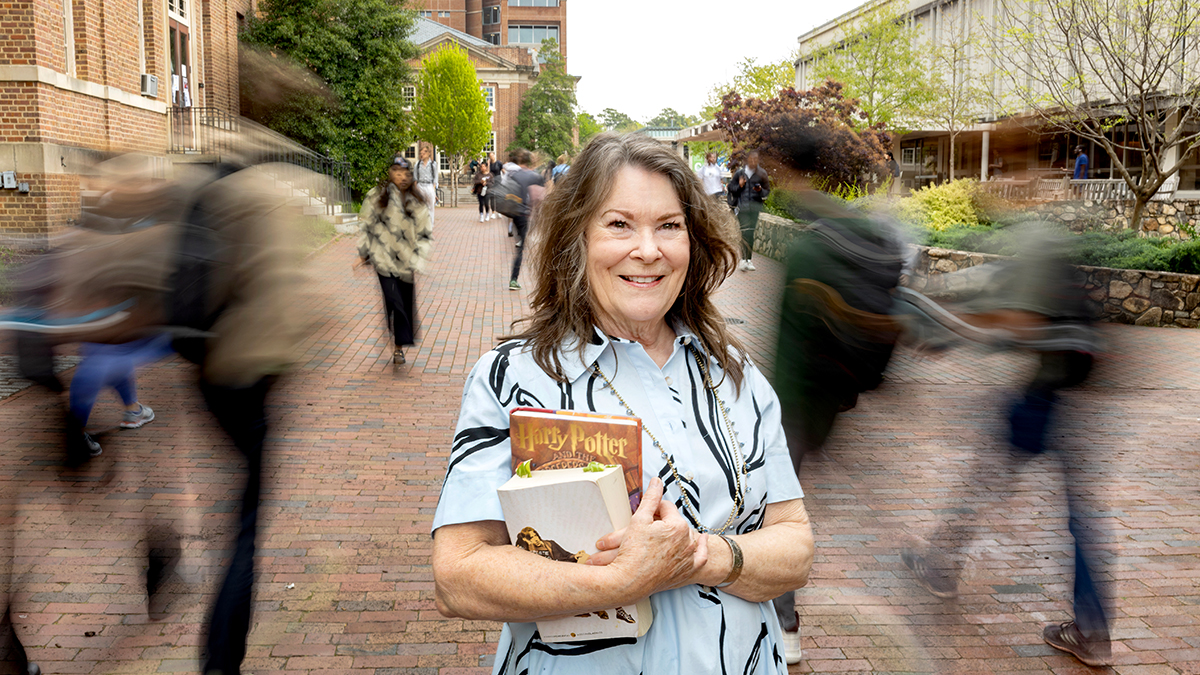

Dorothy Espelage of the School of Education pioneered school-based bullying studies that have led to prevention programs.

For many students today, school is not a safe space.

According to the National Center for Educational Statistics, one out of every five students has been a victim of bullying — and that’s exactly the research specialty of Dorothy Espelage, the William C. Friday Distinguished Professor of Education in the UNC School of Education.

Espelage and UNC-Chapel Hill are hosting the World Anti-Bullying Forum in downtown Raleigh Oct. 25-27. Launched in 2017 by a Swedish nonprofit called Friends, WABF seeks to end violence against and between children. This is the first time the conference will be held in the United States.

The Triangle is a powerhouse for bullying research. Carolina, Duke, NC State, North Carolina Central University and Fayetteville State University have been engaged in the field for decades. UNC-Chapel Hill is a national leader in the related fields of public health, social work and psychology.

But the U.S. lags behind its international partners in anti-bullying efforts, according to Espelage. While bullying rates across the nation are down 10-12%, our collaborators across the world are seeing reductions of 20-50%.

“We led in the beginning but have gone backward because of the political climate around bullying and social-emotional learning,” she says. “As we begin to recover from several years of isolation as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to create safe spaces in our schools, families and communities for youth to be situated in environments that are protective, supportive, equitable and free of bullying.”

Explosion of research

School-based bullying is defined as physical, verbal or social aggression toward one’s peers. It emerges through complex interactions among youth and the systems around them — including school, family dynamics and social media.

When Espelage began researching this topic in the early 1990s, this information didn’t exist. “In 1993, researchers thought bullying was just a male phenomenon,” she says. “And there were only three U.S. papers on bullying.”

The world of bullying research has exploded — in large part thanks to Espelage’s efforts. She was the first scholar to empirically show that bullies are often well-liked and popular, that LGBTQ youth and children with disabilities experience bullying more, and that bullies are more likely to engage in intimate partner violence and sexual assault later in life.

In 2000, Espelage began including cyberbullying measures in her studies, making numerous discoveries. Face-to-face bullying is linked to cyberbullying — and she even helped develop a computer game to compare the two. Child cyberbullies and their victims often receive less parental monitoring and support than their peers. And just like traditional bullies, cyberbullies are more likely to engage in sexual harassment.

Much of Espelage’s work has led to the development of bullying prevention programs. Some are peer-led, which involves training student leaders to guide others by example. Others focus on building social-emotional learning skills like self-awareness, self-control and communication.

“It comes down to relationships,” she says. “If you have strong relationships among students and peers and between students and the administrators and students and the teachers, you have less bullying.”