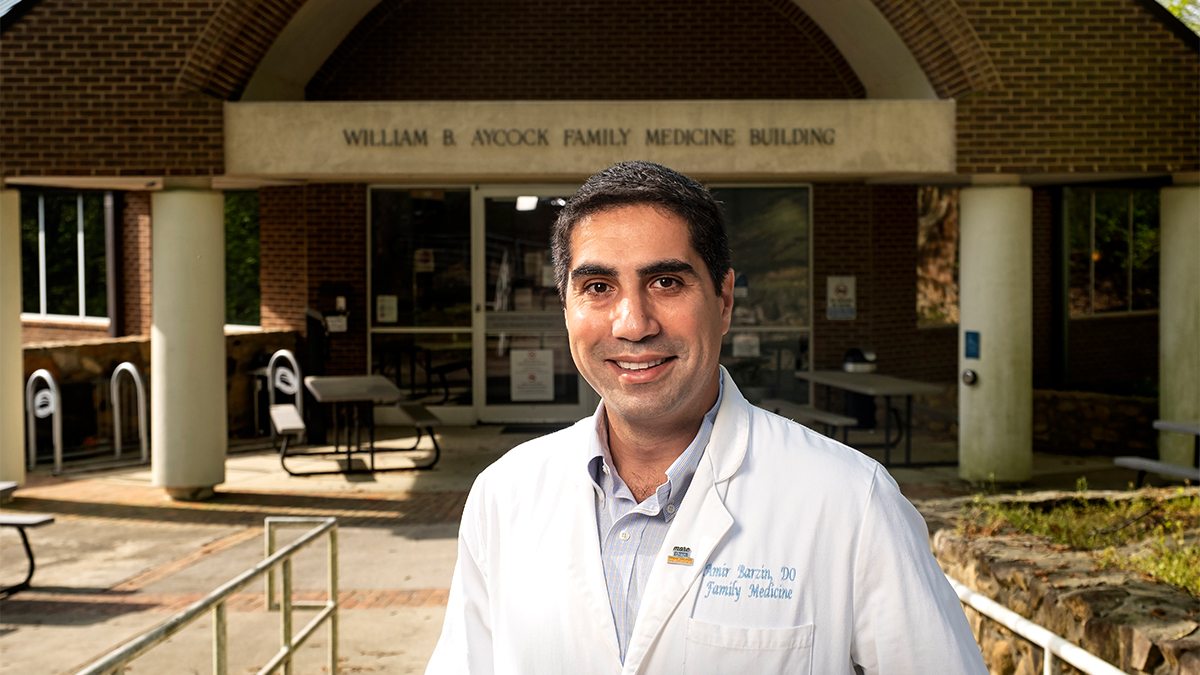

Dr. Amir Barzin answers call to service

When the pandemic hammered the Carolina community, the Massey Award recipient and grateful alumnus dove in to help establish a frontline defense against COVID-19.

The COVID-19 testing labels simply would not scan properly.

It was early January 2021, following 11 weeks of superhuman effort to stand up the Carolina Together Testing Program. The first student samples were flooding into the COVID Surveillance Laboratory — only to pile up due to a technical bottleneck.

“Poor Amy was hunched over trying to hand-scan them,” says Dr. Amir Barzin, CTTP director, referring to the lab’s manager, Amy James Loftis. What should have taken four minutes per run of around 400 samples was taking two hours. With multiple runs per day, the malfunction kept Barzin and Loftis in the Genome Sciences Building past 2 a.m. each night and back at dawn the next morning.

“There was this huge burden to make it work,” Barzin says. “We had no vaccines. We had no treatment. We didn’t have defense mechanisms.” Identifying COVID-19 carriers and isolating them as soon as possible so they didn’t infect other people was critical. Most of the commercial labs at the time were taking four or five days to return results. Barzin and team were aiming for a 72-hour turnaround.

“Our community needs us,” Barzin recalls thinking. “We have to perform.”

They fixed the scanning issue and streamlined other parts of the process. Within a few weeks, the tide began to turn.

They beat the 72-hour goal and soon were returning results in less than 48 hours.

“I remember sitting in the lab one day, and we were getting in 2,500 samples and resulting 2,500 samples in one day,” Barzin says. “I thought, ‘This is it. We’re doing it!’ That was the sweetest moment.”

For his part in setting up the Carolina Together Testing Program, Barzin — assistant professor in the School of Medicine’s family medicine department and medical director for UNC Health Virtual Care Services and the UNC Health Clinical Contact Center — together with Loftis and Susan Fiscus, received prestigious Massey Awards.

This story is part of The Well’s coverage of the C. Knox Massey Distinguished Service Awards, which recognize “unusual, meritorious or superior contributions” by University employees. Look for new recipient profiles to come or find others you might have missed.

Proven leader

When the chancellor and provost picked Barzin to oversee the CTTP, he had proven himself a capable leader more than once at Carolina, his alma mater and a place he says he feels deeply indebted to.

Most recently was in March 2020, when he became incident commander of North Carolina’s first drive-through COVID-19 testing site, the Respiratory Diagnostic Center, which he helped establish with Dr. David Wohl. During that first pandemic summer, Barzin, wearing an N95 mask and surgical gown, worked outside in the heat for hours on end, reaching through car windows with a stethoscope and nasal swabs.

He could have delegated. But, he says, “I hate sitting on the sideline and telling people what to do. I have to be in the work. I have to understand it. So if people are going to sit out there and swab someone’s nose to see if they’re positive for COVID, you better believe that I’m going to be out there swabbing someone’s nose.”

“(Amir) and the team navigated logistical challenges to create such an efficient operation, worked outside each day in the North Carolina summer and truly functioned as one cohesive team,” wrote Cristy Page, School of Medicine executive dean, about that experience in her Massey Award nomination letter. “We constantly heard from people who had come to the RDC for testing just how easy the process was and how the members of the team helped to put their stresses at ease.”

“These people were anxious, scared,” Barzin says. “No one knew what to expect. And we were their contact to health care. We tried to do our best to have a congenial disposition and put people at ease.”

New country, new opportunities

Barzin admits he’s a profound optimist. His mantra — “things could be a lot worse” — is grounded in family history.

Barzin was born in Tehran, Iran, not long after the 1979 Islamic Revolution and during the Iran-Iraq War. In 1988, Barzin’s parents left their home country, taking Amir and his three older sisters to Arlington, Texas.

In Iran, his father had been a general manager of hotels, and his mother had worked for the National Iranian Oil Company. In Texas, they found jobs through a temp agency — his father at the Parking Company of America, where he still works, and his mother with American Airlines.

Neither of Barzin’s parents attended college. Barzin and his three sisters all finished college and received graduate degrees. One sister studied industrial engineering and is a senior executive. Another is the managing attorney for the City of Dallas. The third is a family medicine physician.

Barzin was in high school preparing for college, when 9/11 happened. In the aftermath, his mother, who started out at the airline company making copies and worked her way up the corporate ladder, lost her job.

Around that time, Barzin received a Morehead Scholarship from Carolina. “That’s one of the reasons why I’m so indebted to UNC, because I don’t think I would have had the opportunity that I had if it wasn’t for the Morehead,” he says.

His family also inspired his enduring gratitude. “My parents made a pretty big sacrifice to come to the United States. They left the country that they knew — my dad still prefers to speak in Farsi — and they did it for us,” he says. “They were just trying to make a life for me and my sisters. And then my sisters were great role models and super hardworking and super dedicated people.”

After receiving both a master’s degree and a medical degree from the University of North Texas Health Science Center, Barzin returned to Carolina for his residency in family medicine.

He lives in Chapel Hill with his wife, Anna, daughter Ruth, 3, and son Jack, who turns 1 in June. In addition to his many leadership roles, Barzin still sees patients.

“I feel privileged to be able to take care of patients, but I also feel a great sense of dedication to this University for the opportunities it gave me,” Barzin says. “Things could be a lot worse. I could have stayed in a country going through a war.”