Drug-checking project cuts overdoses

Supported by the N.C. Collaboratory, epidemiologist Nabarun Dasgupta and his team analyze street drugs and alert communities about dangers.

A few years ago, Nabarun Dasgupta went to a drive-thru COVID-19 testing site and left with an aha moment that’s now helping prevent overdoses in North Carolina. The senior scientist at the UNC Injury Prevention Research Center looked at the plastic test kit — vial and swab included inside — and thought, “We should be able to do the same thing with street drugs.”

He was right.

A pharmaco-epidemiologist devoted to battling the drug overdose epidemic, Dasgupta ’13 (Ph.D.) is putting his drive-thru idea into overdrive. It’s now part of a service project supported by the North Carolina Collaboratory that monitors the state’s illicit drug supply and offers alerts to protect North Carolinians through an online database. The mission: prevent deaths and limit other harms by telling people what’s in street drugs and how they can protect themselves and help doctors treat overdoses and addiction with more precision.

The project is needed more than ever. In 2021, a record 4,041 North Carolinians died of a drug overdose, a 22% increase from 2020.

“With 100,000 people (nationally) dying a year, something isn’t working. What we have been doing isn’t enough,” said Dasgupta, who is the first Gillings School of Global Public Health Innovation Fellow. “It’s time for new solutions.”

Throughout the state, harm-reduction groups, public health departments and clinics are mailing in tiny, inactivated drug samples — compliant with Drug Enforcement Administration and postal regulations — using Dasgupta’s innovative, COVID-19-inspired test kits for analysis at the UNC Street Drug Analysis Lab for free.

From there, the lab publishes its results and communicates the findings with the groups, empowering them to use that information to best serve their local community.

They can find out whether their community’s supply has the emerging adulterant xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer that can cause deep skin wounds and other life-threatening issues, and contact healthcare professionals if so. A community group might submit a sample on behalf of someone who had a bad experience to learn that what was expected to be cocaine actually was a mix of fentanyl and other filler substances, stressing the importance of fentanyl test strips. Another group, as one in western North Carolina did, might even get confirmation that the local methamphetamine becomes more dangerous following local drug busts and urge caution during those times.

“The coolest part about this, I think, is watching how other people take the technology and use it to answer their own questions,” Dasgupta said.

Dasgupta is not new to innovative solutions. Last year, he helped end a nationwide shortage of naloxone, the crucial overdose-reversing antidote, through a first-of-its-kind collaboration between his nonprofit Remedy Alliance and pharmaceutical companies.

He said research on street drugs is typically reactive instead of proactive. The latter is what’s needed to make a difference in a person’s life.

“If we really believe in preventing drug-related harms and overdose, then we need to get ahead of the ever-changing drug supply,” Dasgupta said.

Dasgupta and his team began this work in 2022. They test drug samples from across the U.S., but Collaboratory funding, which made the testing free for North Carolina groups, has increased the number of in-state partners from eight to 30.

“The Collaboratory was created by the legislature to serve the people of the state, and this type of project exemplifies that mission,” said Greer Arthur, research director at the Collaboratory, which has received $1.9 million from the N.C. General Assembly to support opioid abatement and recovery projects.

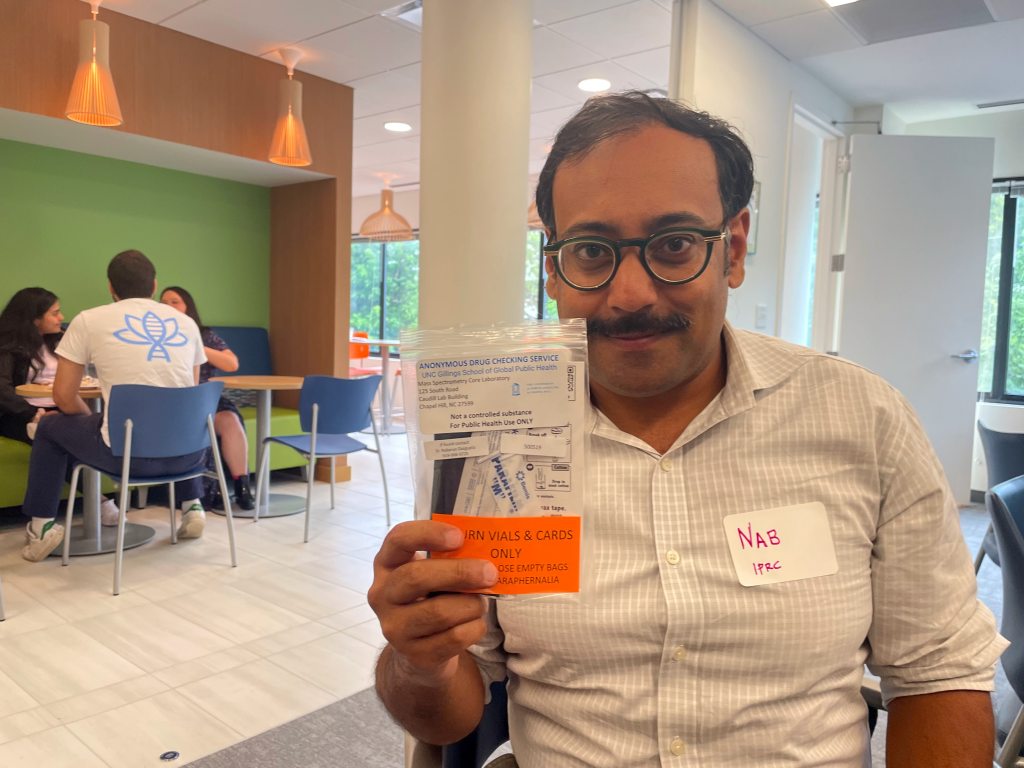

Nabarun Dasgupta, a senior scientist at the UNC Injury Prevention Research Center, poses with a drug-testing kit he created at the Sheps Center on June 20, 2023. (Brennan Doherty/UNC-Chapel Hill)

Looking for a positive impact

When research chemist Erin Tracy runs a drug sample through the chemistry department’s gas chromatography-mass spectrometry machine at Caudill Labs, she’ll look at a nearby computer monitor and see a graph generated in live time. GCMS is a way to “separate and identify components in a mixture,” she said. Through her years of experience, Tracy can quickly decipher what she’s looking at even before the official results from the 17-minute run come in.

“I can look at this and I can tell you it’s fentanyl,” said Tracy, referring to the unique signature the substance has.

Before coming to Carolina, Tracy worked as a forensic chemist for law enforcement agencies in Georgia and Wake County. In joining Dasgupta’s team, she was looking for an opportunity that could have a “positive impact on the community.”

Data turned into action

Using chemistry — and in this case GCMS — to study drug contents is not new or revolutionary. GCMS has been around since the 1950s, Tracy said. Dasgupta said machine-powered drug-checking in the U.S. goes back to the Woodstock era. The technology often is utilized in criminal court cases.

The idea that it can be used in another way to help people can take some getting used to, but the possibilities are becoming evident.

Take for instance the group in Robeson County curious about the potential presence of xylazine in their community. Once it was confirmed that it was in the drug supply, they were able to alert individuals and law enforcement and tell doctors that the skin wounds they were seeing in patients were different from traditional ones caused by infections. That distinction has impacted the treatment people receive.

“People who would have had a leg amputated were able to avoid that amputation because of the difference between an infection versus a chemical burn and how you treat them,” Dasgupta said.

The project’s version of drug-checking is part of a larger harm-reduction strategy that centers those who use drugs. People aren’t ostracized for using. But they are encouraged to take precautions to protect themselves, including cutting back or stopping use.

The work done by Dasgupta and his team helps with that. It’s one thing to be told over and over again to carry naloxone because you never know when you might overdose. It’s another to see that advice paired with a lab analysis showing what exactly is in the drugs from your own neighborhood.

“This group in Fayetteville has repeatedly said that people — once they see that heroin isn’t just heroin or fentanyl isn’t just fentanyl and that they’re putting all these other things in their bodies – want to hear about options on how to cut back or stop their use,” Dasgupta said.

That idea makes sense to Allison Lazard, an associate professor at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media and a health communications expert.

“You think of the Weather Channel,” Lazard said. “It’s kind of a thing — ‘oh, there’s tornadoes in North Carolina.’ ‘Oh, there’s a tornado coming to Chapel Hill.’ Now I care and will do something to protect myself.”

Making the message clear

Test results of the drug samples are posted on the project’s website. Lazard and her collaborators at Hussman help design alerts with advice created by Dasgupta on the website, making sure they’re easily understood and convey the most important points. For example, the webpage of test results from a sample that contains xylazine will also include a message on the serious skin problems it causes and offer a warning about how it can knock you out quickly. The webpage with test results of a drug containing fentanyl will feature bolded suggestions: “Carry naloxone (Narcan) to reverse overdoses.” “Don’t use alone.”

“We’re really thinking about can we communicate certain information in a timely manner that will prevent people from dying,” Lazard said.

That has always been the goal. But now, with the state of the overdose epidemic necessitating it, Dasgupta feels there is a growing appetite for creative answers — mail-order drug testing included.

“North Carolina is the kind of place where if you do this respectfully, with the right intent and adapt it to our circumstances, there’s a lot of compassion and a lot of interest in finding better solutions,” he said.