Students played key role in testing for lead

Collecting samples from campus water sources gave undergraduates and graduate students real-world scientific experience.

It’s another case of Carolina’s students showing their love of science and willingness to serve.

After lead was detected in three Wilson Library drinking fountains in summer 2022, Carolina’s Environment, Health and Safety formed a plan to test water fixtures in every campus building.

There was lots of ground to cover. With hundreds of drinking fountains, bottle refill stations and kitchen sinks in some 250 buildings across campus, protecting campus would require a small force trained to follow the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s protocol.

Cathy Brennan

To help enlist that force, EHS executive director Cathy Brennan turned to faculty adviser Rebecca Fry, the Carol Remmer Angle Distinguished Professor in Children’s Environmental Health and director of the Institute for Environmental Health Solutions in the Gillings School of Global Public Health. Fry also directs the UNC Superfund Research Program.

Fry and other faculty members put out a call for student volunteers who wanted to satisfy scientific curiosity, fulfill volunteer hours, complete a class assignment or simply help.

In September, EHS trained Fry’s lab staff and the first wave of student volunteers, whose numbers reached 29.

Audrey Bousquet, research specialist in the Gillings School’s environmental sciences and engineering department, and three graduate students trained a steady stream of volunteers. Bousquet asked for the students’ availability then put together weekly schedules. Armed with building floor plans, students fanned out across campus to work 1-3 hours per week.

“I was genuinely impressed with the student volunteers,” said Bousquet. “Each week, I paired up with a new student to sample so I could learn more about everyone helping out, and every student was so passionate about the issue. They were responsive and trustworthy with their work. I knew I could send them out on their own to test and believe they had done the job properly. We made many adjustments along the way as we learned how to best go about the testing process, and they were always extremely adaptive.”

Rebecca Fry

Fry said that universities are not required to test for lead in drinking water. Still, the University worked to develop a “no lead tolerance policy” informed by the EPA’s lead and copper rule set in 1991. This requires water utilities and providers — note that Carolina is not a water utility — to act if more than 10% of their customers’ water samples are above 15 parts per billion of lead.

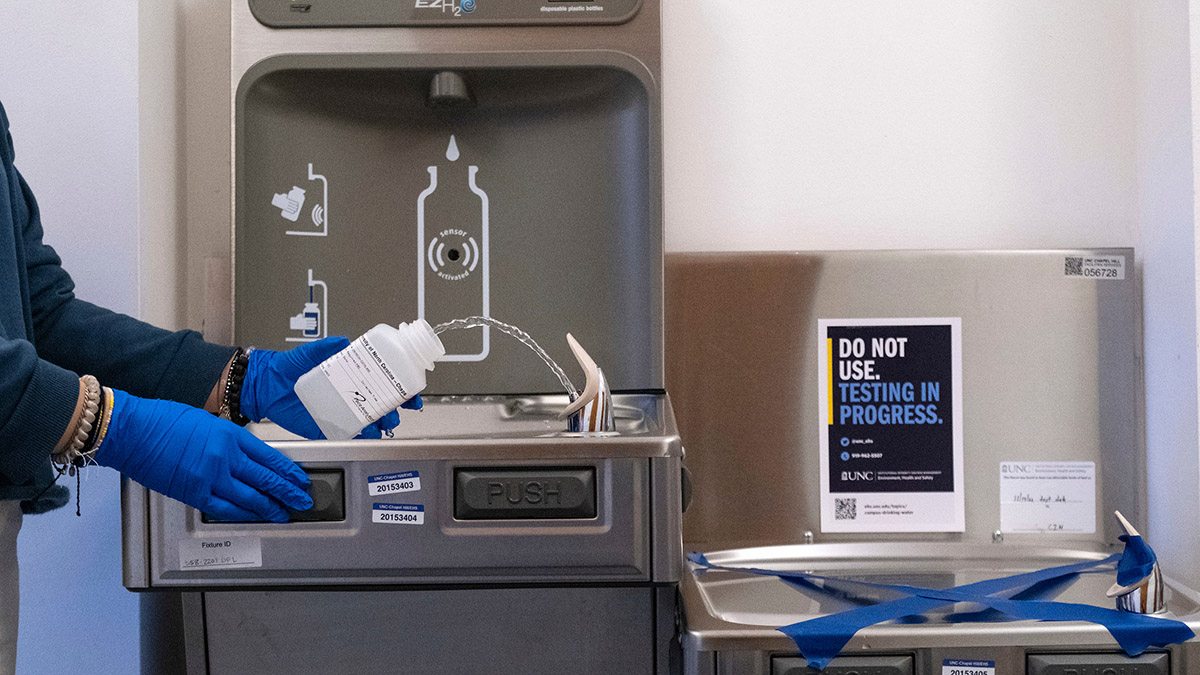

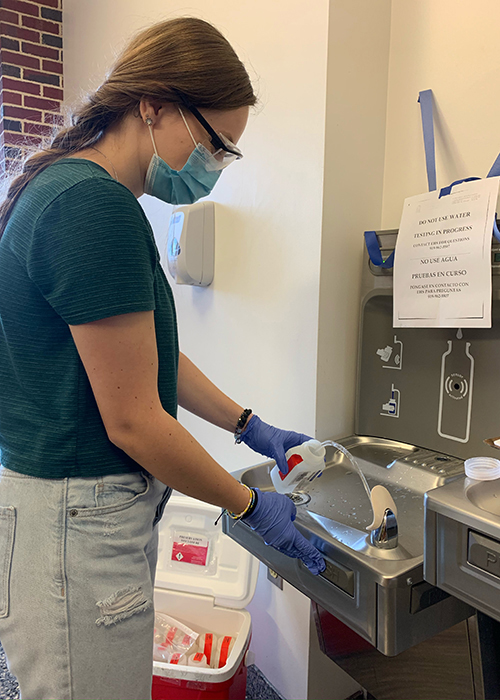

Sampling takes two days. On the first day, testers flush fixtures for 15 minutes in the afternoon to ensure that the water to be sampled the next day sits undisturbed for 8-18 hours. They tape off fixtures to keep them out of use. Early in the morning on the second day, they draw samples — two from water fountains and one from sinks — and take the samples to the Fry lab for distribution to testing agencies. Fixtures remain out of use until test results come back.

To support the student testers, EHS industrial hygiene staff coordinated supplies and transported samples to testing agencies.

Under the University’s no-lead policy, fixtures that test positive for lead remain out of use until Facilities Services replaces parts or the entire fixture as quickly as possible, said Brennan. Facilities Services provides water filling stations in buildings during testing and afterward if fixtures remain out of use.

Celeste Carberry, a doctoral student in the ESE department who conducted well water testing as an undergraduate, said she wanted to help with a time-sensitive issue like lead testing. “This was a unique opportunity to get hands-on experience. Seeing how Dr. Fry and EHS developed a phased approach and how that played out in real time was cool,” she said. “I work a lot in cell culture toxicology, so this was a bigger picture. I got to see how my research could impact a real-world solution.”

Kristina Stuckey, a student in the ESE master’s degree program, said, “I had previously worked with pathogens but not metal sampling. Water sampling definitely will be in our future because exposure to metals is becoming prevalent. Water sampling goes on all the time and having that skillset is a good thing. Plus, it’s a timely issue for the University.”

Audrey Bousquet, research specialist in the Gillings School’s environmental sciences and engineering department, fills a sample bottle. Bousquet and three graduate students trained many of the student volunteers.

The first wave of trainees volunteered every week for two months. Others worked about half that amount as their part in the process ended in December. The students collected samples in 19 buildings, including Beard Hall, Fetzer Hall and Boshamer Stadium.

Anastasia Freedman, an ESE doctoral student, took samples and trained others. “When we were sampling and evolving the protocol, it was impressive to see how fast changes were made and implemented,” she said. “We started by recording things on paper, but then quickly made an online system. Seeing the quick turnarounds spoke to how united and motivated everyone was to accomplish this goal.”

Hannah Matthews, a senior environmental health sciences major with a sustainability studies minor, said that she volunteered “to learn more about the situation, but also be a part of the solution and help push things forward. I wanted to see what went on behind the scenes to solve this large health issue.”

Testing, in its final phase, will be completed by semester’s end, said Brennan.

Fry said that the students and their efforts are valuable for two reasons. “First, this rapidly increased the understanding of the levels of lead in drinking water on campus. Second, this provided the students with hands-on experience dealing with an environmental science issue. The students have commented that they really appreciate this opportunity to work with EHS and the UNC Superfund Research Program to help our community.”