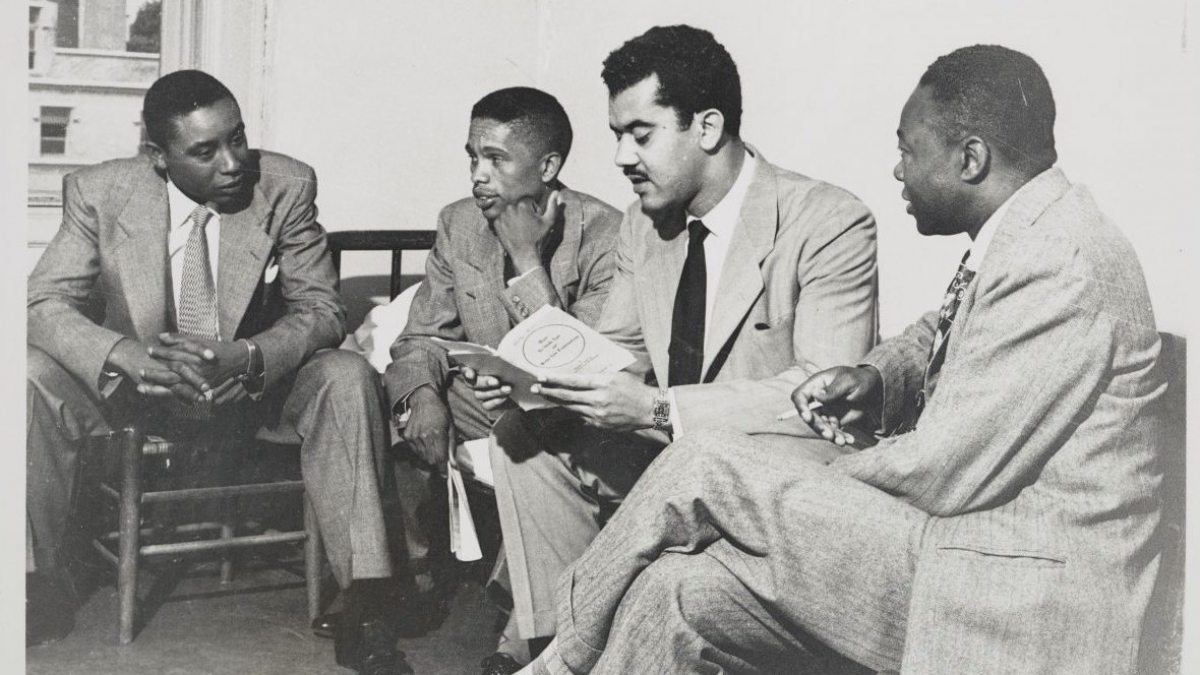

225 years of Tar Heels: Harvey Beech, James Lassiter, J. Kenneth Lee, Floyd McKissick and James Robert Walker

The five UNC School of Law students desegregated the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1951. By the mid-1950s, black students were admitted to the College of Arts & Sciences.

Editor’s note: In honor of the University’s 225th anniversary, we will be sharing profiles throughout the academic year of some of the many Tar Heels who have left their heelprint on the campus, their communities, the state, the nation and the world.

Editor’s note: In honor of the University’s 225th anniversary, we will be sharing profiles throughout the academic year of some of the many Tar Heels who have left their heelprint on the campus, their communities, the state, the nation and the world.

In 1951, five African-American students enrolled in Carolina’s School of Law. The move effectively desegregated the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

They were able to enroll after a 1949 lawsuit filed by students from North Carolina Central University School of Law seeking admission at Carolina. They were represented by Thurgood Marshall, who, at that time, was the director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and later would become an associate justice on the U.S. Supreme Court.

The students who enrolled were Harvey Beech, James Lassiter, J. Kenneth Lee, Floyd McKissick and James Robert Walker.

After they enrolled, other graduate and professional schools at Carolina began admitting African-American students. By the mid-1950s, black students were admitted to the College of Arts & Sciences.

McKissick had already received a law degree from North Carolina College (now North Carolina Central) School of Law, but he enrolled in the summer session at Carolina and took one course. Beech, Lee and Walker graduated in 1952. Lassiter earned his degree from another institution, according to Charles Daye, who was the first African-American faculty member at the UNC Law School.

“I just felt like we ought to open up all the windows and doors and air it all out,” Beech once said, according to an article the UNC General Alumni Association published after Beech died in 2005. “If I hadn’t, some other child would have had to. Something had to be done – it wasn’t pleasant. We won a war for something that had been denied to other black boys.”

Today, the UNC GAA recognizes the former students with awards in their names. Beech also had received the William Richardson Davie Award, the highest honor given by UNC Board of Trustees and the Distinguished Service Medal from the GAA.