Carolina Tree Heritage program brings new life to downed tree

South Building, which opened in 1814, just gained a new detail that has been in Chapel Hill longer than the historic building itself: A 5-foot wide, 400-pound table made from a 251-year-old post oak tree that stood behind Old West on the edge of McCorkle Place until 2018.

South Building, which opened in 1814, just gained a new detail that has been in Chapel Hill longer than the historic building itself.

A 5-foot wide, 400-pound table that was installed earlier this month and now sits in the rotunda is made from a 251-year-old post oak tree that stood behind Old West on the edge of McCorkle Place until 2018.

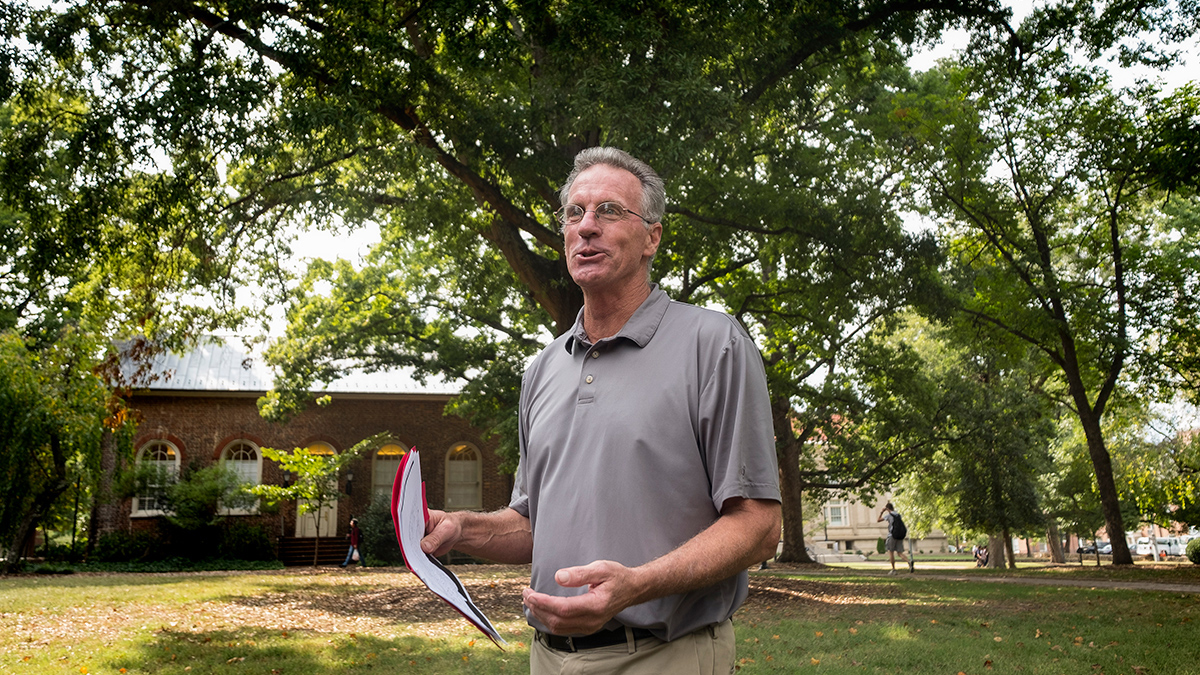

When the tree developed a disease and became a safety risk, alumnus and professional woodworker Michael Everhart ’13, ’19 (MCRP) knew the tree’s story didn’t have to end there. He helped launch the Carolina Tree Heritage program, which takes the wood from historic trees that come down on campus during storms or for safety reasons and transforms them into furniture.

The large table in South Building is one of the first pieces Everhart has created through the Carolina Tree Heritage program.

“Many of the trees on our campus have witnessed our university’s entire history,” said Chancellor Kevin M. Guskiewicz. “It is an honor for all of us in South Building to welcome visitors to sit at this table and see that history in its rings. I am grateful for the work of Michael, Susan and the Carolina Tree Heritage program to keep the legacy of these trees alive.”

Everhart transformed the wood from a raw tree section, known as a cookie, into a finished table in less than a month and shared some details about the process he followed.

What are some of the specifications of the post oak tree and the table it became?

The cookie is around 60 inches in diameter, and the table weighs about 400 pounds. The legs and the pentagram inset that holds the base together are also made from lumber out of the same tree. While making the table, I discovered five bullets that were fired into the tree roughly 175 or 200 years ago. The bullets came out during the flattening process, but the scar tissue that the tree formed around three of them is visible on the top of the table and two others are visible from below.

What was your process for creating the table?

Building this table was a straightforward process but was made complicated by its size and weight. To begin, the slab was flattened on one side using a router and “sled,” a pair of parallel rails, and a massive surfacing bit. The router sled rides on the rails with the bit at a fixed depth, taking even and progressively deeper passes back and forth until the entire surface is smooth and shows fresh grain. At that point, the voids and cracks in the wood were covered with tape and then thin plywood to hold in the three gallons of epoxy while it sets later in the process.

Building this table was a straightforward process but was made complicated by its size and weight. To begin, the slab was flattened on one side using a router and “sled,” a pair of parallel rails, and a massive surfacing bit. The router sled rides on the rails with the bit at a fixed depth, taking even and progressively deeper passes back and forth until the entire surface is smooth and shows fresh grain. At that point, the voids and cracks in the wood were covered with tape and then thin plywood to hold in the three gallons of epoxy while it sets later in the process.

When the cookie first came to the shop, it was barely holding itself together. The wood needed to be stabilized and held together mechanically to prevent future cracks from propagating, but we wanted to build the entire table from this tree without any fasteners. I built a pentagon with half-lap joints and routed it into the base one-inch deep and flush with the bottom. I drilled holes for the legs on a bench press, then hammered the legs in and glued them in place.

I then built a temporary frame to hold the table while it was flipped over so that the top side was up, and the router sled process was repeated, this time using the flat plane of the bottom as a reference surface for the top. I removed material until the entire top was in plane. At that point, it was lots and lots of sanding, and then lots and lots of oiling.

What were the biggest challenges involved in this project?

The biggest technical challenge was that the piece was just so heavy. It was difficult to move around the shop. Often when building a piece, I flip it over countless times as the work progresses. That was not possible with this piece, and I relied on the assistance of several good neighbors whenever a flip was required.

You’ve been involved with Carolina Tree Heritage and the concept of reusing wood from Carolina’s historic trees for years. What was it like to deliver the table and see your vision fulfilled?

The Carolina Tree Heritage project has been a group effort that I am grateful to have been a part of. It has been made possible by the dedicated efforts of those involved. The program is largely the product of my master’s project when I was a student in the Department of City and Regional Planning and learned the news that this great post oak would be coming down.

The Carolina Tree Heritage project has been a group effort that I am grateful to have been a part of. It has been made possible by the dedicated efforts of those involved. The program is largely the product of my master’s project when I was a student in the Department of City and Regional Planning and learned the news that this great post oak would be coming down.

At the time, central to my vision was the idea that pieces of campus lumber would end up back on campus as pieces of furniture. Seeing this vision realized now, three years after this particular tree came down and two years after I graduated, is simply fantastic. That I was able to build the piece, and that it now resides in a prominent location on campus, makes it all the more impactful for me.

As an alumnus of this University, what’s it like to use your talent to help give back to Carolina like this?

Being a part of this project is a real joy for me because I have been involved with UNC for a long time, and the project combines so many of my interests. In addition to my master’s of city and regional planning, I earned a bachelor’s in environmental science from UNC in 2013. That department is housed in the Institute for the Environment, which is also home to Carolina Tree Heritage.

Between these stints at UNC, a woodworking hobby turned professional, and I spent a few years making custom furniture, often with slabs and unique live edge pieces. In so many ways, this program really has come full circle for me, and I hope to continue to be involved with building the program and contributing to the UNC community.