Galápagos: A gateway for global research

For more than 10 years, the UNC Center for Galápagos Studies has been a hub of collaborative research activity spanning many disciplines, with the potential to impact the globe. Diego Riveros-Iregui and Amanda Thompson, the center’s new interim co-directors, strive to use their own experiences from the islands to expand its reach and grow its reputation as a world-renowned research institution.

Since Charles Darwin conducted his famous finch studies that led to his theory of evolution, the Galápagos Islands have been heralded as a destination for seeing incredible wildlife. Today, more than 275,000 tourists visit the archipelago each year, supported by over 30,000 residents, most involved in tourism. It is not merely an attraction for vacationers, but a haven for researchers interested in terrestrial ecology, marine ecology, and human-environment interactions.

UNC-Chapel Hill is the only non-Ecuadorian institution with a presence on the islands today — a feat made possible, in large part, thanks to geographer Stephen Walsh. Now a distinguished emeritus professor, Walsh spent over 15 years building relationships with the right people to form and grow both the UNC Center for Galápagos Studies — a group of North Carolina researchers with projects on the islands — and the Galápagos Science Center, a fully staffed physical building on San Cristobal that is a joint partnership between Carolina and the Universidad San Francisco de Quito.

Before Walsh set his sights on the Galápagos, he conducted research in the western U.S., Thailand and the Ecuadorian Amazon and is well-versed in the logistical problems that come with international projects. Having a physical location in a foreign country is a big deal. It not only provides the technical infrastructure to run experiments but the personnel and partners to help solve complex problems.

“Social networks are important if you’re going to be somewhere long-term,” Walsh says. “You want to be viewed not as a visitor, but as part of the community.”

Since 2006, Walsh has visited the islands more than 50 times — but that’s just a guess because he’s lost count. He went so often because he wanted to create lasting relationships, to be more than a transient face. He made friends in the community, the local government, the hospital, and at Galápagos National Park.

“You have to have coffee with people. You have to have dinner with people. You have to have a beer with people,” Walsh says with a laugh. “And that’s when you begin to build trust, respect, and relationships.”

Walsh had to build relationships at Carolina, too — with scientists and leadership to support the Galápagos Initiative.

In 2013, he met Diego Riveros-Iregui, a new hire in the geography department who was trying to organize a project in Colombia but was struggling with the logistics, like finding a Colombian collaborator and the facilities to run experiments while abroad. In response, Walsh invited him to visit the Galápagos, a place where UNC-Chapel Hill was quickly growing its presence.

“When I went there, I realized I could ask the same questions I was already asking in Colombia, and I would have a lot more logistical support. For me, it was an easy decision,” Riveros-Iregui says.

Diego Riveros-Iregui and Amanda Thompson are the interim co-directors of the UNC Center for Galápagos Studies. Riveros-Iregui is a geography professor who specializes in hydrology. Thompson, a professor of anthropology and nutrition, studies issues related to human biology. (Photo by Andrew Russell)

Around the same time, a similar exchange occurred between Walsh and Kelly Houk, a Carolina graduate student attempting to work in the Amazon Rain Forest. Like Riveros-Iregui, Houk was encountering a slew of hurdles. Come to the Galápagos,encouraged Walsh. So she did.

Houk’s first field season in the Galápagos was a successful one, and while planning a return visit, her advisor Amanda Thompson asked to accompany her. It didn’t take long for Thompson, a human biologist, to realize her own research would translate well there.

“The Galápagos are a unique opportunity to do integrated, planetary research in a small space,” Thompson says. “They serve as a test case that we can expand from and apply to other places.”

Often called a “living laboratory,” the islands experience many issues common to other places — like food insecurity, poor water quality, and limited infrastructure. While it might take years to gather data on these topics in larger countries, the Galápagos’ small size cuts that time in half.

A similar thing happens on an environmental level. Because the archipelago sits on the equator and at the intersection of three major ocean currents, they experience a series of microclimates, meaning the weather patterns and landscapes change within just a 10-minute drive in any direction.

“The example I always think of is how California has experienced periods of drought for the last decade,” Riveros-Iregui says. “In the Galápagos, you would feel the effects of a drought immediately. Everything is more pronounced. So the decisions we make there in response to changes in climate and the ecosystem are a lot more urgent.”

Thompson and Riveros-Iregui have been members of the Center for Galápagos Studies since 2014. Both have conducted, and are still engaged in, multiple projects on the islands and have served on the Galápagos Advisory Board, as well as faculty research directors to Walsh. They have watched the Galápagos Science Center grow to include more than 100 researchers working on over 100 projects. Upon Walsh’s retirement in January, they became the interim co-directors of CGS, which they will oversee for the next 18 months until a permanent director is appointed.

“They held the right positions, the right scientific focus, and they had proven their mettle in other capacities,” Walsh says. “It was clear to me that they would do a great job representing Carolina in the Galápagos.”

Thompson will manage most of the center’s administrative tasks, like developing a five-year plan and maintaining relationships within the International Galápagos Science Consortium, a network of collaborating institutions and scientists. Riveros-Iregui will focus on encouraging more Carolina faculty, staff, and students to conduct research in the Galápagos, streamlining data management and sharing, and growing the study abroad program.

“I keep joking that you need both of us to fill Steve’s shoes,” Thompson says, chuckling. “It’s just amazing what he was able to build in the past 10 years.”

Endeavorsspoke with Thompson and Riveros-Iregui about conducting research in a foreign country, how research impacts the Galápagos, and what they hope to achieve as interim co-directors.

How do both the Center for Galápagos Studies and the Galápagos Science Center make conducting research in a foreign country simpler for all involved?

Riveros-Iregui studies water on the islands and is engaged in projects analyzing fog and soil minerals. (Photo by Andrew Russell)

Diego Riveros-Iregui:The advantages of both centers are that we all understand those challenges, and we are equal partners with a local university, USFQ, in the Galápagos Science Center — the only university science facility on the archipelago. We have four different laboratories, a classroom, a conference room, and office space for researchers, students, and visitors. That way, when students and researchers travel to Galápagos, they can focus on the work and not on the logistical challenges.

Amanda Thompson:The scientific and administrative staff at the Galápagos Science Center are extremely helpful in dealing with the logistical challenges of getting supplies to the islands, hiring research assistants, and facilitating day-to-day details, like travel arrangements and lab access.

What are each of you researching in the Galápagos?

AT:My background is in human biology, and I’m interested in how early life environments shape health outcomes like obesity and other chronic and infectious diseases. When I went to the Galápagos, I found out that 60% of babies were being born by C-section. The U.S. doesn’t encourage elective C-sections, in part because they are associated with limited breastfeeding. That made the Galápagos an interesting place to look at how C-sections affect child immune development, infant feeding practices, and growth in kids.

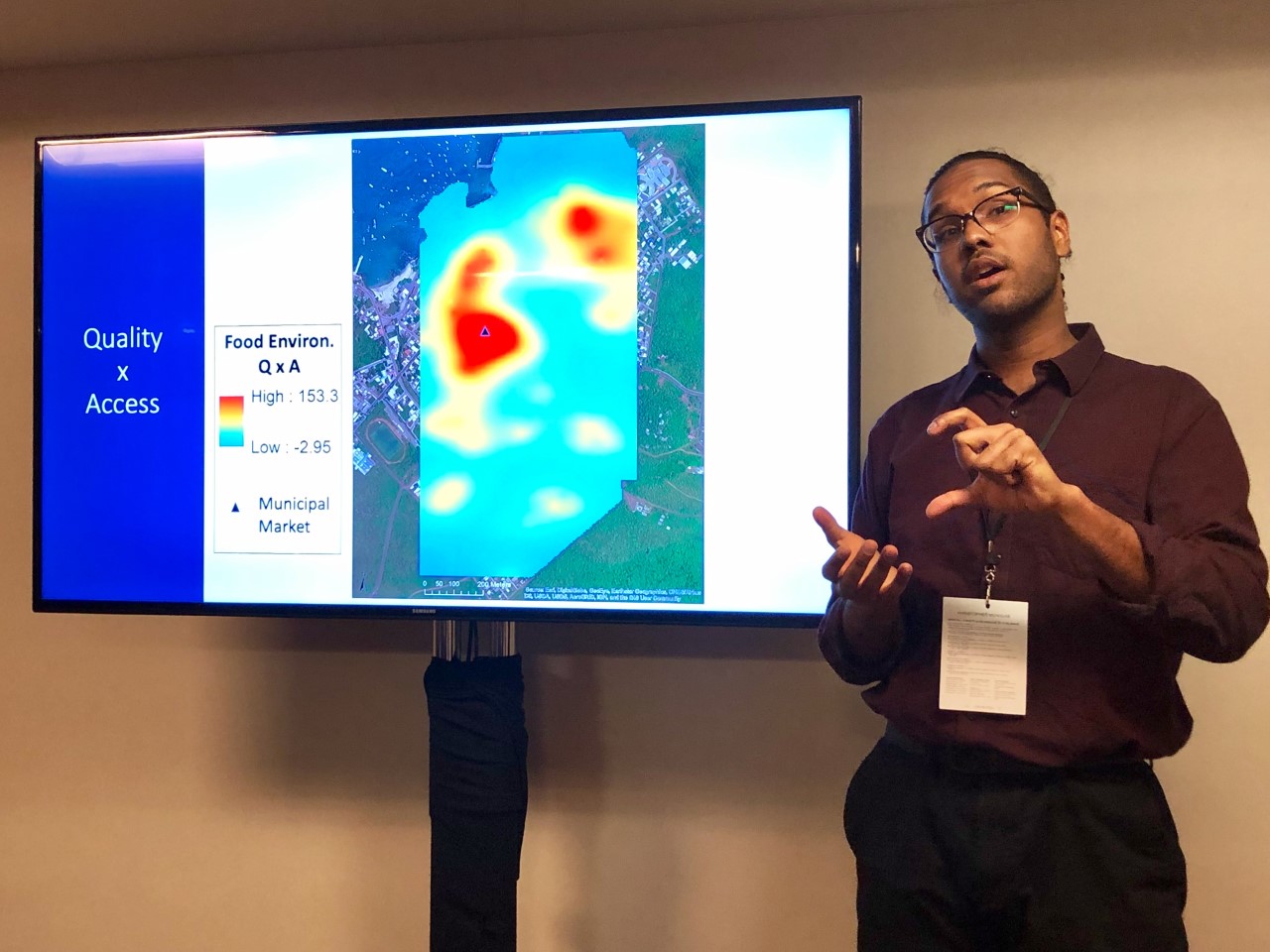

As a human biologist, Thompson studies how water quality, food insecurity, and diet quality in the Galápagos are associated with infectious and chronic diseases and mental health conditions. (Photo by Andrew Russell)

While working on that project and going into households, many mothers told me they were concerned about water quality, infections, and the quality of their kids’ diets. That led to additional projects on water quality, food security, and diet quality, and how those are associated with infectious and chronic diseases and mental health conditions.

DRI:I’m a hydrologist, and I study water — a critical resource in the Galápagos because it is limited by seasonality. There’s a rainy season, and then for about six months of the year, it doesn’t rain. But the islands see a lot of fog, especially up in the highlands. My initial project was looking at the chemistry and fate of this fog — how deep into the soil it gets and whether plants use it or not.

Another project looks at the type of minerals that are formed in the soil. In an archipelago like the Galápagos, the islands are relatively young and have been formed through volcanism. They are all made of similar rock and are exposed to different microclimates and amounts of water. At low elevations, the climate is very dry, but if you go up to the highlands there is rainfall and fog. This leads to different kinds of soil and makes the highlands a better environment for agriculture.

Why is research important for people who live in the Galápagos?

DRI:About 30,000 people live on the archipelago, and they are directly impacted by the research that we do. For example, when it rained in the highlands, people by the coast would get sick. Researchers discovered that as this water made its way down to the coast, it contained more pathogens — information that was used to push for installation of a new water treatment plant.

AT:Also, when the new hospital was built, administrators were worried that people wouldn’t utilize the hospital as much as they thought they would. They asked us to interview key stakeholders and community members about their perceptions of the hospital. We submitted a report to them, and they ended up instituting some changes based on those recommendations.

Each of you have been members of the center for eight years. How would you like to see it evolve now that you’re interim co-directors?

DRI:My long-term dream is that the Center for Galápagos Studies becomes a well-known place for island research and that people know about UNC’s involvement. I’d like to see it attract more researchers from Carolina and researchers all over the world.

AT:That’s exactly what I would say. It’s an exciting interdisciplinary research site that has the potential to impact global challenges, like climate change, sustainability, food and water availability, and biodiversity.

DRI:And global education — the opportunity for Carolina students to study in the Galápagos with Carolina faculty. Both Amanda and I have taught in the Galápagos several times and have seen the impact this has on students.

AT: Students who study abroad in the Galápagos often point to it as their favorite part of their Carolina experience. That’s something we want to continue to enhance and provide opportunities to do.

Read more stories on Carolina’s researchers at Endeavors.UNC.edu