‘SERVICE’ paints picture of Black history

The lunch counter mural in the School of Government serves up important people and events from the state’s past.

Throughout Carolina's history, there have been several pioneers who have broken down barriers for the generations of students to follow. Their courageous examples moved UNC-Chapel Hill closer to the ideal of the University of the people.

As the University celebrates Black History Month this February, learn more about Tar Heels who paved the way for a more inclusive university.

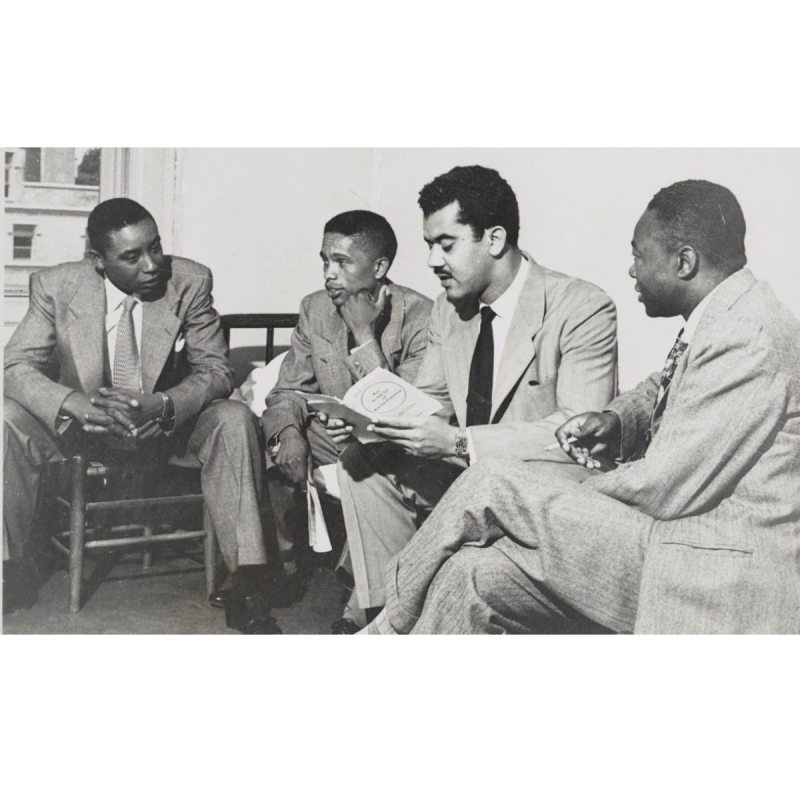

Harvey Beech, James Lassiter, J. Kenneth Lee, Floyd McKissick and James Robert Walker enrolled in the UNC School of Law in 1951, following a court order that said the Law School must admit Black students. They became the first African American students at Carolina. After they enrolled, other graduate and professional schools at Carolina began admitting African American students.

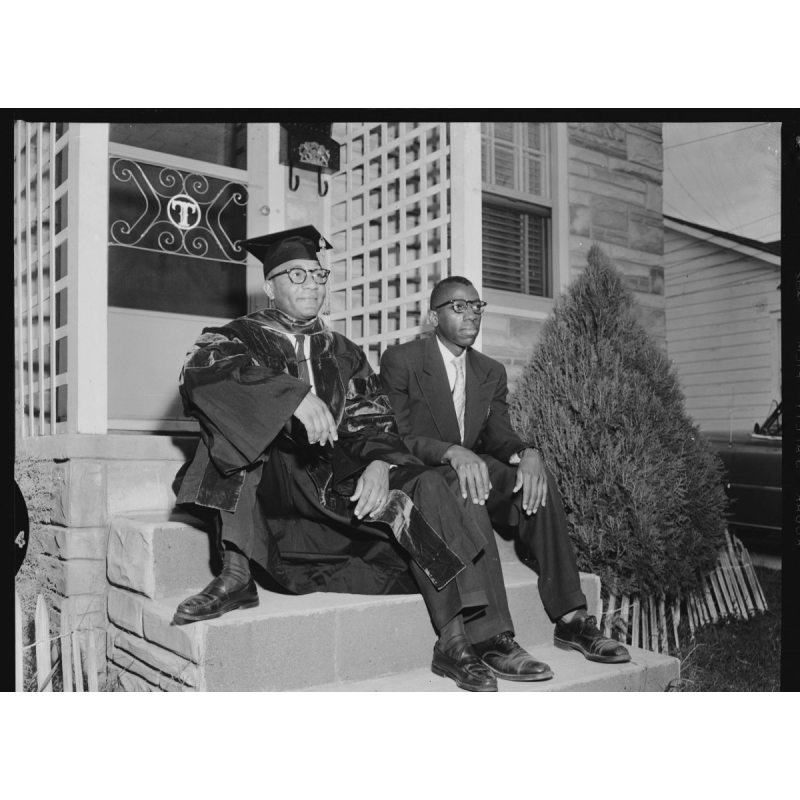

The same legal ruling that opened the door for Carolina’s first African American law students also made way for Oscar Diggs, in 1951, to become the first African American to attend Carolina’s medical school. Diggs graduated in 1955, becoming the first African American doctor of medicine from the University.

By the mid-1950s, Black students were admitted to the College of Arts & Sciences.

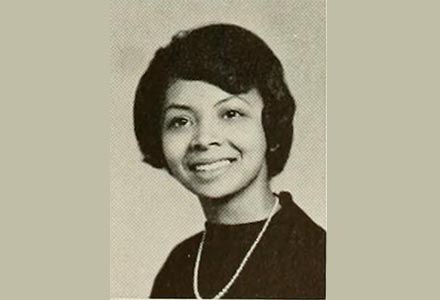

When Karen Parker arrived at UNC-Chapel Hill in 1963, she was the first African American undergraduate woman to enroll at the University. At Carolina, she continued to fight for her rights while earning a bachelor’s degree in journalism.

As a student, Parker kept a diary of her experiences at Carolina, including descriptions of her arrests on campus. Parker donated the diary to the Southern Historical Collection of UNC Libraries in 2006.

Hortense McClinton was the first Black professor hired at Carolina, accepting an appointment with the UNC School of Social Work in 1966 and retiring in 1984. During her time on faculty, she regularly taught courses on casework, human development, family therapy and institutional racism.

McClinton also helped to establish the predecessor organization to the Carolina Black Caucus and worked with various units on campus to improve services for students with disabilities. In 2022, the University renamed a residence hall after McClinton.

The work hasn’t stopped with these trailblazers and history makers. Today’s Tar Heels are continuing the traditions of Carolina's Black pioneers by working toward a more inclusive and stronger future that is propelling the University and communities forward.

Whether it’s through amplifying the voices of underrepresented students, shining a light on culture, conducting crucial research or creating new opportunities for others to thrive, current students and faculty are continuing to break down barriers and pave the way for new generations.

The lunch counter mural in the School of Government serves up important people and events from the state’s past.

Carolina music professor Naomi André wants Americans to know more about the song “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

Trevy McDonald’s class shows the value of these “eyewitnesses to history” who fought for civil rights.

The School of Government’s Kimalee Dickerson connects them through the Engaging Women of Color conference.

Psychologist Shauna Cooper studies the role of Black fathers in child development and promotes parenting support for them.

Black women die from childbirth at higher rates than white women. The School of Medicine’s Venus Standard hopes to change that.

Having lost his grandfather to the disease, the medical student works to develop new treatments at Lineberger.

Through her health policy studies and skateboarding, Louise Hoff is finding community in Chapel Hill.

Founded by Tar Heel Nehemiah Stewart, Level the Playing Field builds a hiring pipeline for diverse students.